By Izzy Ross, Interlochen Public Radio

This coverage is made possible through a partnership with IPR and Grist, a nonprofit independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

The five Great Lakes are among the fastest-warming bodies of water on Earth. They contain one fifth of the world’s freshwater, and climate change is affecting the ecosystems, people and industries that depend on them.

But major uncertainties and research gaps affect how governments and communities respond, according to the new National Climate Assessment.

The report lays out an in-depth look at climate change in regions across the United States. Hundreds of experts and scientists contributed, aiming to provide governments and communities with useful information and analyses.

In the Great Lakes, there are worrying risks for fisheries and habitats as ice cover decreases and oxygen levels drop. Invasive species and decreased biodiversity are among the greatest threats — both can affect water quality by increasing toxins and changing the food web. More drought, flooding and runoff will likely harm ecosystems by increasing erosion, harmful algal blooms and allowing for more invasive species.

As the winters have warmed, insects have expanded throughout the Great Lakes. Deer ticks are spreading Lyme disease across the Midwest, including in Michigan.

The report says many effective solutions are grounded in local knowledge, Indigenous leadership and collaboration with tribes and communities.

Agriculture

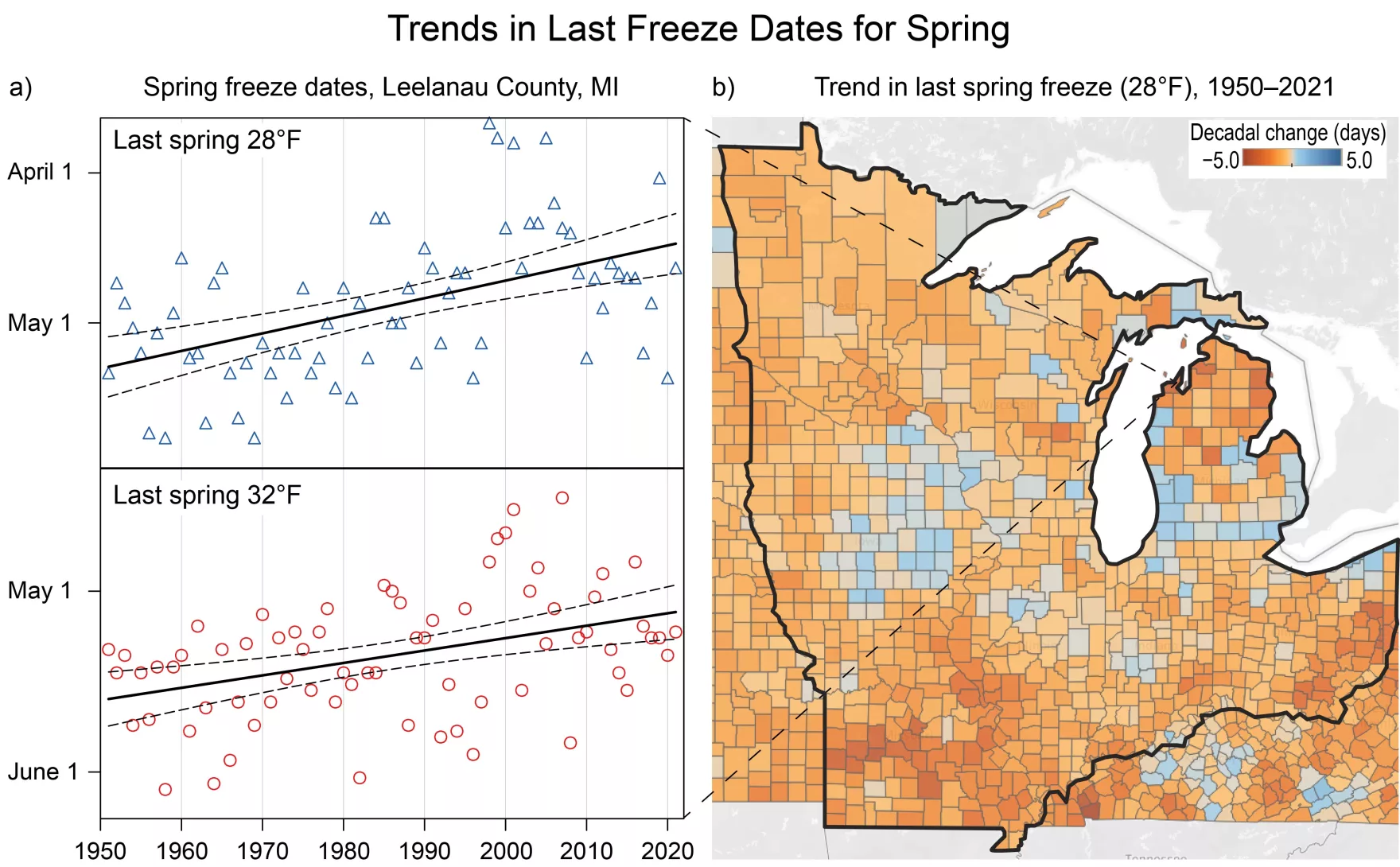

Temperatures in Michigan have increased an average of 2 – 3 degrees Farenheit over the past century. The report uses northern Michigan’s Leelanau County as an example of winter’s last freeze taking place earlier.

One of the biggest impacts of climate change in northern Michigan and across the Great Lakes is on agriculture, a $14.5 billion industry in the region.

Trends (solid black lines) show that the last date in spring when minimum temperatures fall to either 28°F or 32°F in Leelanau County, Michigan, are occurring earlier in the year. Adapted with permission from the Midwestern Regional Climate Center’s Freeze Date Tool. Map base layer on right is by Mapbox. (National Climate Assessment, The Ohio State University, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center)

Farmers have already experienced huge fluctuations in productivity and damage. There have been more swings between excessive moisture and intense drought in recent years — a trend that’s expected to continue. That affects everything from spring planting to crop yields.

Wetter conditions mean crops are more susceptible to disease. Hotter and drier conditions in the summer can mean more weeds and less harvest. There’s also an increase in pests, which have moved north over the past century.

Because the weather is warming earlier in the year, specialty crops like apples and cherries bloom sooner. A spring frost that hits after they bloom can damage or kill them. These shifts have caused pollinators to decline, which means less productive crops.

People across Midwest farm country are working to adapt, using “climate-smart” techniques — approaches that could help crops and reduce or eliminate greenhouse gasses — like reduced tilling, planting cover crops, and using land for both renewable energy projects and agriculture.

The report says public and private partnerships can help, and government agencies are also working with communities to adopt techniques.

To reduce fertilizer and nutrient runoff into streams, rivers and lakes, for example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration created a tool to help farmers know when to apply fertilizer. That will reduce the amount of chemicals like nitrogen and phosphorus running into the waterways and make harmful algae blooms and lower oxygen levels less likely.

Waterways

The Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio rivers are vital transportation routes. Shipping goods via waterways also uses less fuel and emits less carbon. But as water levels fluctuate with more erratic precipitation, those routes are less reliable. That could lead to delays in deliveries of food and supplies.

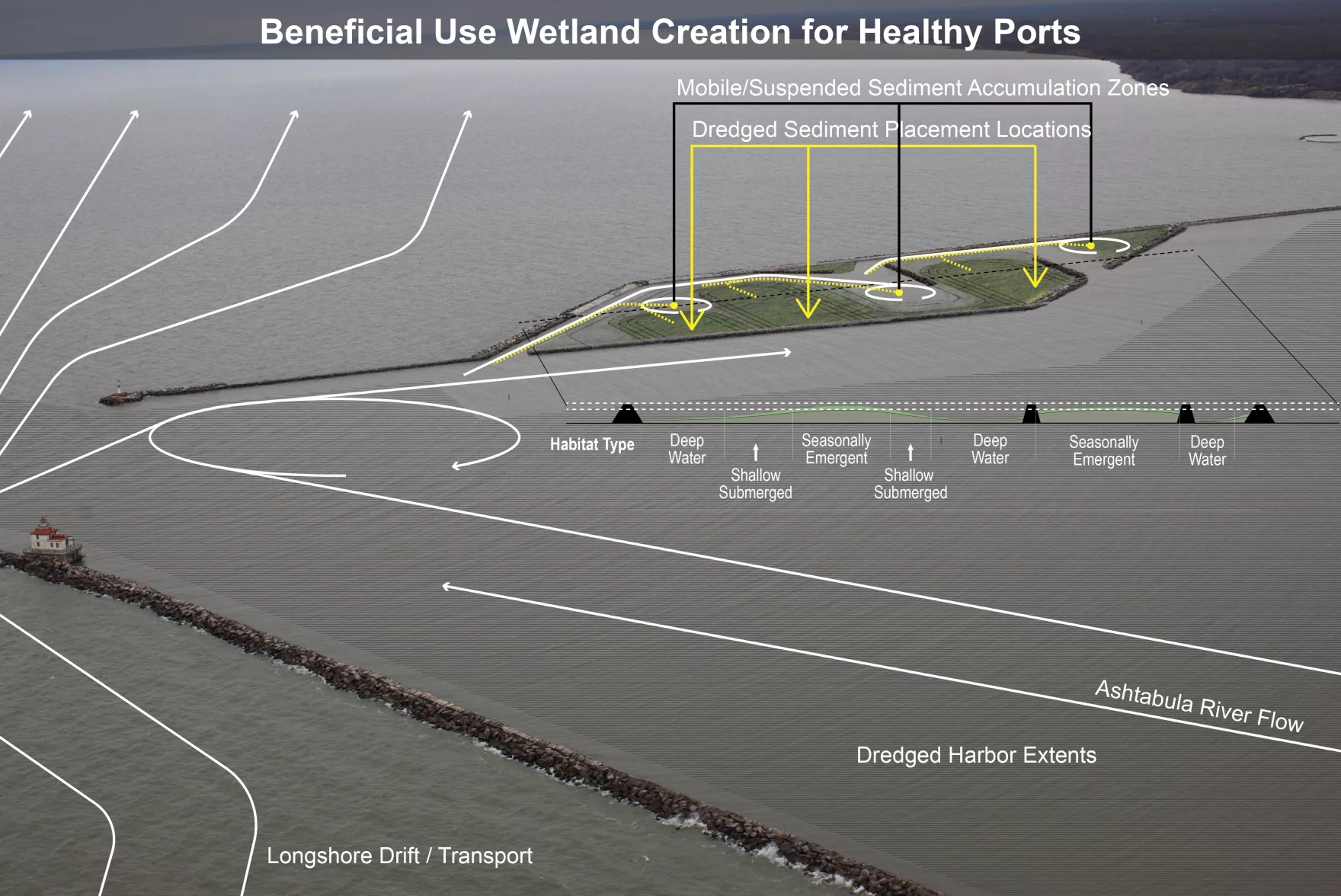

The variety of the Great Lakes’ waters and shores means that any solutions must be closely linked to local environments, economies and communities. That means ports have a critical role to play in helping communities and governments address changes in the coming years.

Some communities are experimenting with a new kind of port management by restoring the ecology of the area, which the report says can also improve social health.

The image shows an overview of the harbor in Ashtabula, Ohio, the site of a wetland creation project by the US Army Corps of Engineers with support from Healthy Port Futures. This project, which works with the flow on the Ashtabula River into Lake Erie, was one of the first attempts in the Great Lakes to establish a partially open wetland system with reused dredge material. This design permits an occasional, ecologically necessary disturbance that will promote wetland complexity while also allowing for an important hydrological connection to the nearshore. (National Climate Assessment, Adapted from Burkholder et al. 2022.)

Indigenous self-determination is key

Indigenous peoples have stewarded the lands and waters of the Great Lakes for thousands of years. As climate change alters the environment, it threatens their well-being, livelihoods, health and traditions.

Wild rice is central to tribes across the Midwest, including in northern Michigan. It’s one of the culturally important species most vulnerable to climate change. Harvest rates can decrease due to warming and changing waterways, which can impact many peoples’ cultural identity. As winters warm, the harvesting time for sugar maple sap is changing. When snow cover shrinks, the change endangers the wildlife that depends on it, like moose.

One chapter in the report explores the challenges Indigenous communities face, how they’re addressing those problems, and what’s needed for them to sustain Indigenous climate resilience.

Settler colonial abuses of Indigenous rights bear “significant responsibility for climate disruption.”

“The U.S. government’s taking of land from Indigenous peoples has increased vulnerability to climate disruption,” the report’s authors say.

Indigenous communities often face inequitable access to data, planning assistance and support for climate adaptation from the federal government.

Despite this, communities and leaders have continually worked to respond to these challenges.

“For the last six decades, the Indigenous peoples’ movement to address climate and energy issues has generated new knowledge of the severity of environmental risks and the solutions for fostering a sustainable and ethical world,” said lead author Kyle Whyte in a University of Michigan post. Whyte is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and a professor at the university.

Tribal networks like the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission are creating planning and adaptation resources. They’re also leading research in their regions and collaborating with non-Native entities.

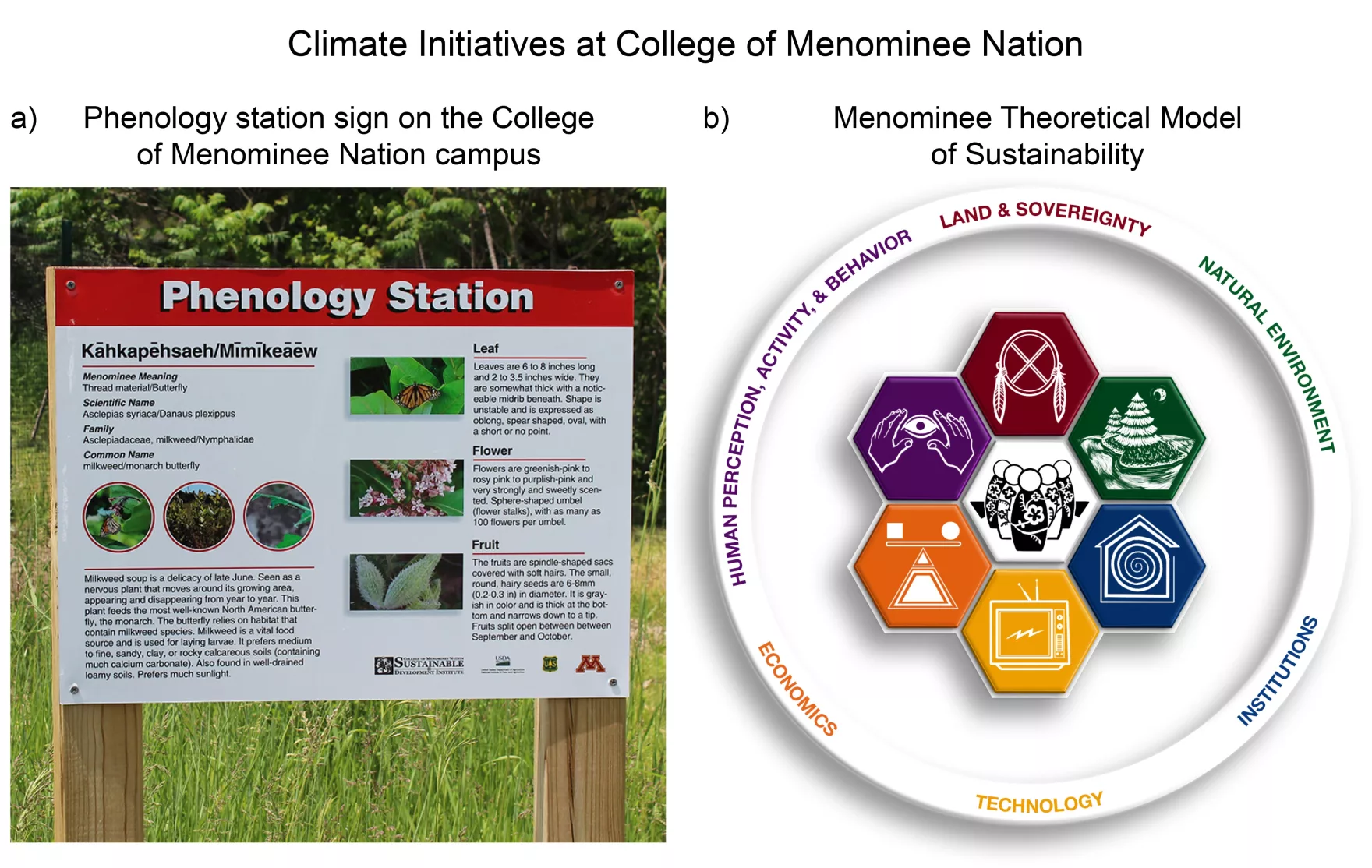

Tribes and Indigenous organizations are leading climate response, pursuing renewable energy projects, food security initiatives and adaptation plans.

The report included the example of the Dibaginjigaadeg Anishinaabe Ezhitwaad — a Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu based on Ojibwe and Menominee world views, and designed for other Indigenous communities to tailor to their own cultures.

A phenology station sign at the College of Menominee Nation in Keshena, Wisconsin. The phenology project explores the effects of climate change on the reservation forest and community over time. The college has also developed the Menominee Theoretical Model of Sustainability (b), which guides climate change research, education, and community outreach and is an example of Indigenous leadership for climate adaptation. (National Climate Assessment, (left) Thomas R. Kenote, College of Menominee Nation Sustainable Development Institute, (right) the Menominee Theoretical Model of Sustainability).

The importance of Indigenous self-determination is essential to meeting communities’ needs. That means Indigenous peoples decide how to respond to climate change in ways defined by their communities.

Colonial policies and institutions often impair these efforts, and result in federal, state and local governments and industries making decisions for Indigenous communities and not providing enough funding or other support.

That’s led many tribes to call for Indigenous-led management, as well as organizational assistance, and data that is culturally relevant, accessible, and owned by the community.

For effective climate management, the report says, communities also need sufficient options for adaptation and mitigation, and the capacity to implement and revise decisions.

‘Major uncertainties’

Because of the complex mix of ecosystems, industry and people in the Great Lakes region, the report says predicting climate change impacts is a challenge: “Current climate trends are, in some ways, counter to projected climate conditions and differ from other regions of the country.”

That uncertainty makes planning difficult.

The report says governments must do more to work with Black, Indigenous and people of color communities and low-income communities in order to support adaptation efforts the communities are already pursuing.

Other serious research gaps include the trade-offs of climate-smart agricultural practices, how seasonal warming is affecting farming and how shifts in agriculture impact social equity and justice.

Still, the report says that efforts to address climate change across the region provide hope for the future.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

How climate change can confuse fall foliage

Where Do Solar Panels Go To Die?

Featured image: The sun sets over Lake Michigan on Oct. 1, 2023. (Photo: Izzy Ross/IPR News Radio)