Editor’s Note: “Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A direct descendant of the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe, she lives and works in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her two books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and she is at work on a children’s story. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwe, and these features explore the intersection of indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

Water quality specialist Margaret Watkins has been measuring environmental conditions on Grand Portage Ojibwe tribal lands for 28 years. Speaking to her on the phone, you get the feeling you are talking to someone who has been through an epic battle. But instead of weapons of war, Margaret and her team use scientific methodology, aquatic plant and animal monitoring, comparative historical data, and water samples—lots of water samples—in their fight for the health of aquatic-dependent life. A category that includes humans.

In fact, the Grand Portage Band was the first Tribal Nation in the country to have a beach program and has been monitoring water quality at tribally-held beaches since 2007. This includes an annual look at water samples collected at 17 sites. They sample 13 of these sites weekly, and next year they plan to increase their weekly monitoring to 15 beaches.

Margaret and water quality technician Taryn Manthey have also started to check water quality conditions at Chippewa City—an off-reservation beach within the Grand Marais city limits that was re-acquisitioned by the Band in November of 2022. There has been one closure at that site since they began testing in June of 2023. According to the Minnesota Department of Public Health (NDPH), such closures happen when monitoring results show an increased risk of getting sick from swimming or wading. This can happen when a single water sample exceeds an E. coli count of 235 per 100 milliliters. A recent look at beaches monitored by Grand Portage scientists in August showed counts ranging from 0 to 10 per 100 milliliters—nearly pristine conditions.

Water quality at the headwaters of Grand Portage has been excellent for as long as the Band has been conducting research. Based on sediment cores from on-reservation inland lakes and excluding contaminants that have been atmospherically deposited (such as mercury and PFAS), Margaret says that “water quality hasn’t changed in a statistically significant amount in more than 200 years.”

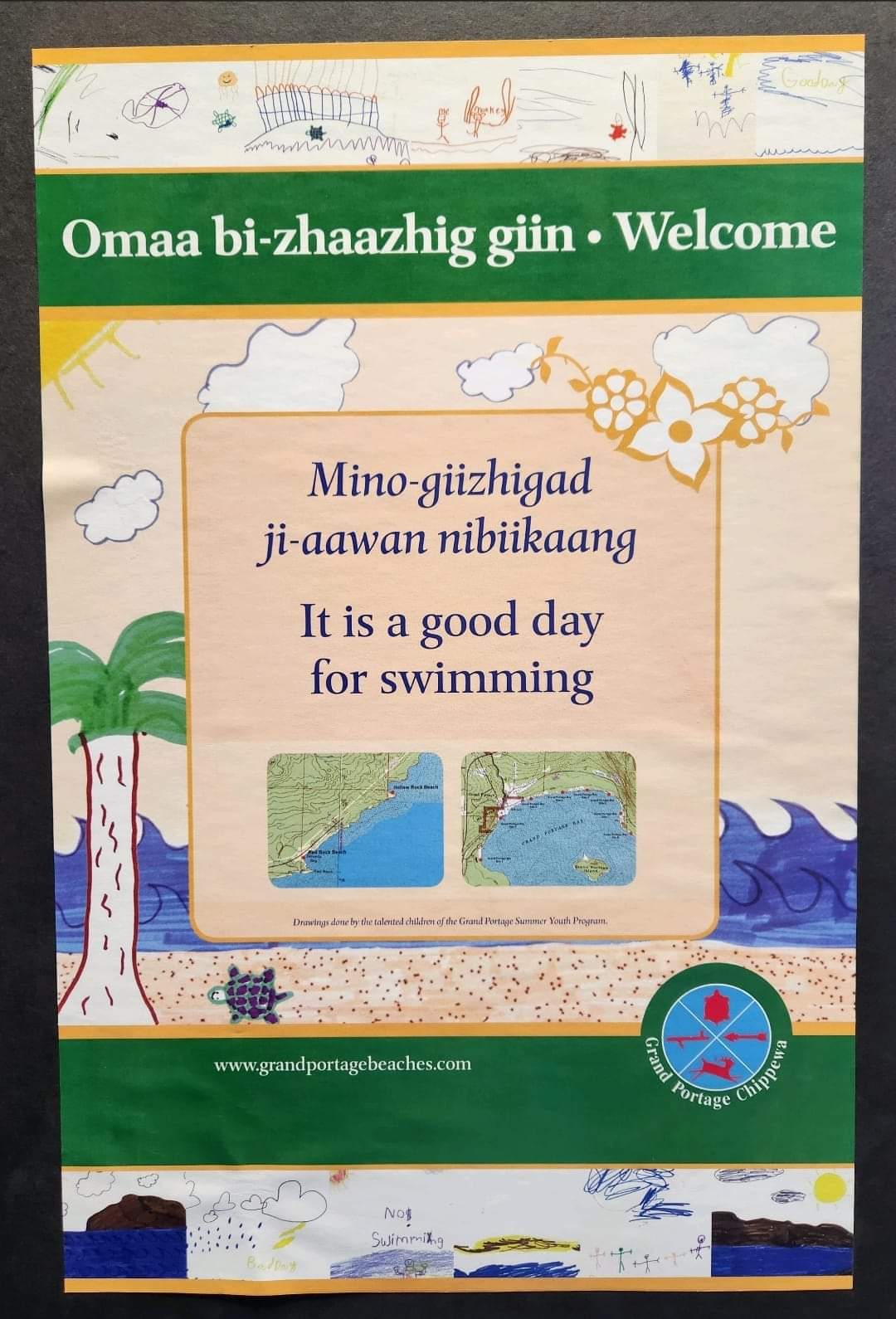

Beach condition poster. (Photo courtesy of the Grand Portage Beach Monitoring Team via Staci Lola Drouillard)

By upholding such high standards, you could argue Chi Onigaming—Minnesota’s smallest Ojibwe nation by population – is creating a buffer for other communities further down the chain that aren’t as respectful or careful when it comes to water quality management.

The Minnesota Department of Health collects localized information for North Shore beaches through the Lake Superior beach monitoring program, which recorded 10 beach closings between June and August of 2023. Those closings included one at downtown Grand Marais, two at Minnesota Point (or Park Point) in Duluth, and one at Black Beach in Silver Bay (a beach composed of residual taconite tailings).

It turns out beach monitoring is technically not required under Minnesota state law, which in my opinion, makes Margaret and her team outstanding models of water stewardship.

Most municipalities along the North Shore rely on volunteers to check water conditions. Ilena Hansel, district manager of the Cook County soil and water district, confirmed that their staff works with youth volunteers when they are available, and their data is shared with the MDPH, which compiles an annual report.

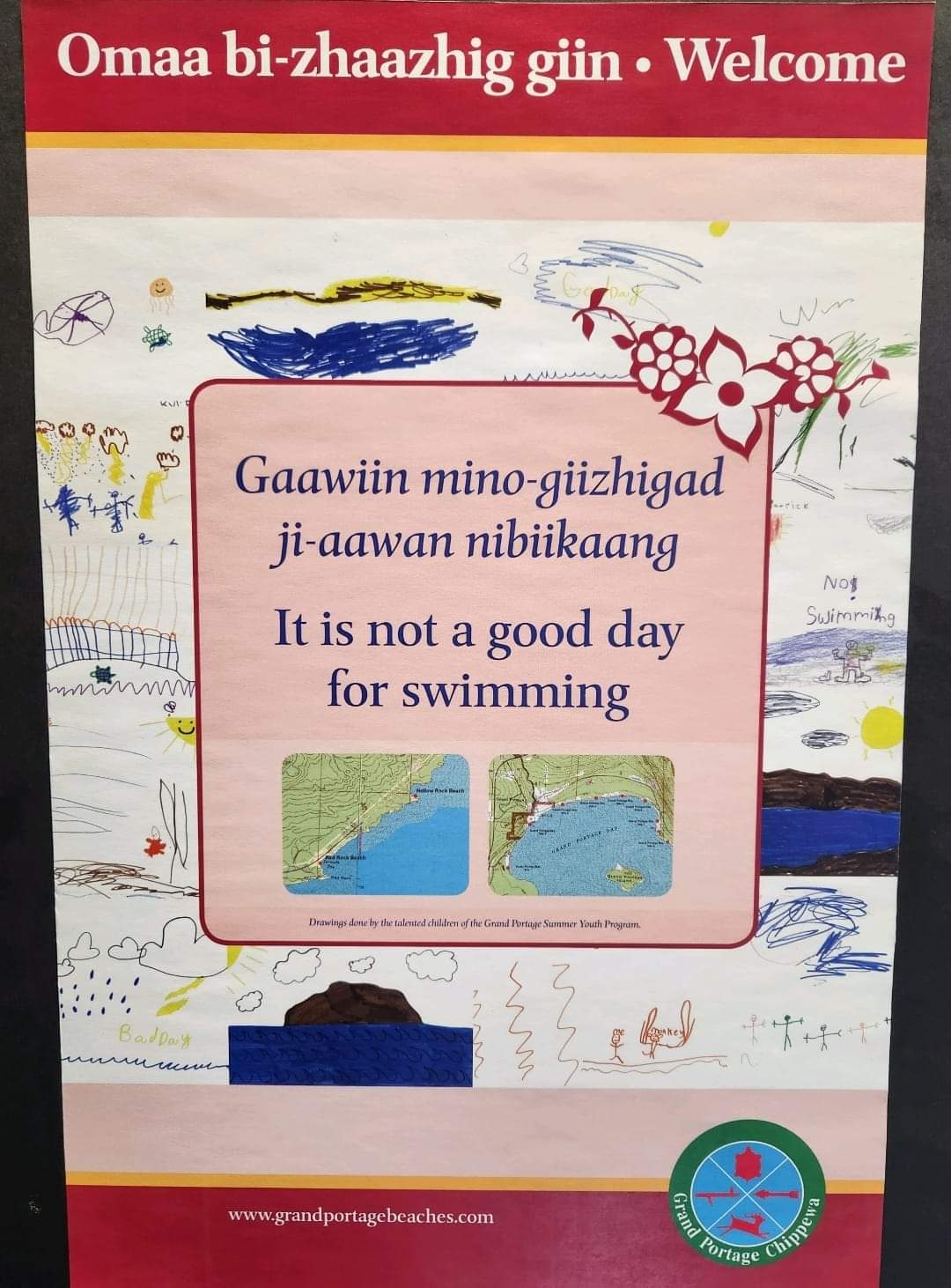

Beach condition poster. (Photo courtesy of the Grand Portage Beach Monitoring Team via Staci Lola Drouillard)

In our blood

Margaret and Taryn take each measurement very seriously, because at Grand Portage, water quality is seen as a matter of life or death. In fact, people in Grand Portage eat a lot of fish, which means that our federally approved water quality standards are stricter than other places.

Based on EPA fish consumption standards, Minnesotans eat 30 grams of local fish per day. By comparison, Grand Portage members consume an average of 142.4 grams per day. When determining the risk to public health, Grand Portage uses a factor of 1-in-a-million, and MN uses a 1-in-one-hundred thousand risk factor to calculate water quality standards. And that negotiated calculation can now go much higher. Margaret shared that, “some of the western Tribes and Leech Lake can use much higher fish consumption values than was possible when Grand Portage water quality standards were federally approved in the late 1990s.” The Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe’s standard is based on eating 260 grams of fish per day and the Confederated Tribes on the Columbia River (Umatilla, Walla Walla) use 620 grams per day. As Margaret says, “the reason Grand Portage has stricter water quality standards than the state is to protect local uses (subsistence fishing, ceremonial use) that are different than state uses.” In other words, Grand Portage people rely on fish and clean water resources because it is in our blood, literally and figuratively.

So, what is considered safe? Concentrations less than 235 colonies of E. coli per 100 milliliters of water is the EPA standard, but “drinking water should not have any bacteria in it, so waters for ceremonial use should be bacteria-free,” says Margaret.

I asked her if Grand Portage measurements ever exceed the standard and she said they sometimes see concentrations above 2400 cfu at Grand Portage Bay and other places. “This likely means there has been significant rainfall and big waves,” she says. “Bacteria wash off the land surfaces into the water and settle to the bottom until wave action re-suspends them in the water column.”

Monitoring for harmful E. coli is just one aspect of the work being done at Grand Portage to protect the health and well-being of nibi—the source of all life on Earth. Scientists at Grand Portage regularly monitor mercury levels in fish tissue in both Lake Superior and inland waters. They also check water bodies for other pollutants like Deet and PFOS, which occur in direct relation to human interaction.

And every five years the wastewater treatment plant needs a new permit, so the Band retrieves mercury monitoring data from the Fernberg Road National Air Deposition Program (NADP) and submits a detailed mercury minimization plan, maintaining the tribal Nation’s “Outstanding Water Resources” classification.

Grand Portage Bay. (Photo courtesy of Cathy Quinn)

The top three threats

Their beach monitoring complete until next year, Margaret and Taryn take on other battles, including collaborating with other Lake Superior Bands to protect water from the threat of new mining industries. Copper-nickel mining is of particular concern because of the risks that hard rock mining poses to upholding the long-held sulfate standard for healthy manoomin—wild rice plants—a water quality standard which has been in place since 1973.

When I asked them to identify what they saw as the top-three factors that lead to poor water quality, the list was comprehensive. Number one is poor land use practices. For example, the Grand Portage land use ordinance requires a minimum of a 75-foot set-back for building next to water. Neighboring Cook County uses a 40-foot set-back.

Next on their list was poorly written or enforced National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) wastewater and stormwater permits, followed by climate change, which “will drive changes resulting from poor permitting and poor land use practices to occur more quickly and with more frequency, like harmful algal blooms.”

After 28 years, Margaret is now poised to retire and she believes it is her duty to prepare for the future of water resources at Grand Portage.

The water quality team’s work is guided by the Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Plan 1854 Ceded Territory Including the Bois Forte, Fond du Lac, and Grand Portage Reservations, published in 2016. To date, no North Shore communities, large or small, have implemented a comparable plan.

To adapt to the anticipated effects of climate change, Margaret and her team advocate for an adaptable approach to infrastructure improvements and the planning process. For example, the Band is installing bigger culverts to handle bigger rainfall events, bigger buffers to treat run-off after major storm events and fine-tuning practices that reduce erosion. They use the climate adaptation plan to guide projects into the future. Due to their consistent monitoring, the Band has data from reservation waters beginning in 1994 so they can follow trends over time.

Protecting drinking water at Grand Portage is part of the Band’s strong record on upholding water quality standards above and beyond what the state, or even the EPA requires.

“None of our work would be possible without the constant unwavering support from the Tribal Council. Their leadership has provided the direction we have taken,” says Margaret.

Adaptable, fearless and unrelenting, Margaret and her colleagues at Grand Portage are our warriors in the fight for nibi.

You can see the results of their diligent work here, on the Grand Portage Beach Monitoring webpage.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Nibi Chronicles: The art of Ojibwe linoleum

Nibi Chronicles: A portal to the Burt Lake Band’s violent expulsion

Featured image: Pancake Island, one of the monitoring sites, photo by Staci Drouillard