By Kelly House, Bridge Michigan

This story is part of a Great Lakes News Collaborative series investigating the region’s water pollution challenges. Called Refresh, the series explores the Clean Water Act’s shortcomings in the Great Lakes, and how the region can more completely address water pollution in the next 50 years.

Funded by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, the collaborative’s four newsrooms — Bridge Michigan, Circle of Blue, Great Lakes Now, and Michigan Radio — will report on overlooked pollutants as well as legal and institutional barriers preventing achievement of the Clean Water Act’s aspirational goals.

- As climate change threatens to warm Michigan rivers, advocates increasingly see removing dams as a remedy

- Michigan has thousands of dams, many of which warm rivers, endangered cold water fish

- New state and federal money has given dam removal efforts a boost, but not without controversy

In the quest to defend Michigan’s rivers against climate change, government officials and fish advocates are increasingly zeroing in on a simple strategy that can lower temperatures by several degrees, and open up miles of new habitat.

Removing dams.

It’s a sometimes controversial technique that’s gaining renewed steam in Michigan thanks to tens of millions in new state and federal dollars, rising costs to maintain Michigan’s old and sometimes-obsolete dams, and a growing understanding of their environmental drawbacks.

“In my career in dams…this is the most investment I’ve seen at all levels” in dam repairs and removals, said Luke Trumble, who supervises the dam safety unit at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy.

Related:

- Consumers Energy tells Michigan residents it needs partners to keep hydro dams

- In warming Great Lakes, climate triage means some cold waters won’t be saved

- Two years after Midland dam failures, still no action on safety reforms

But while Michigan moves faster than ever to take out old and obsolete dams, some river advocates worry it’s still too slow to outpace global climate change that threatens to heat the state’s rivers by several degrees this century.

A growing case for removal

Like most of the country, Michigan’s rivers and streams are plugged with thousands of impoundments, big and small. There are more than 2,500 known dams in the state, and likely more that haven’t crossed regulators’ radar.

In the early days of statehood, many of them helped expand towns and industries by providing local electricity before the state had a comprehensive energy grid, or controlling floods to allow development. Others were built for recreation or industry.

But they came with a downside that few anticipated in those days, said Dana Castle, a fisheries biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

They fragment Michigan’s rivers, denying migratory fish the ability to move freely. And many of them artificially warm the water that backs up behind their impoundments, baking in the summer sun.

“At the time, we didn’t know any better,” Castle said.

The state estimates that 72,000 miles of Michigan rivers are fragmented by dams. The vast majority are not equipped with technology to let fish pass upstream.

And while many of those impoundments still bring value to nearby communities, a growing number are old, obsolete and expensive to maintain. Following a series of dramatic dam failures in Michigan and other states in recent years, interest in removing them has surged.

Consumers Energy, for instance, wants to sell its 13 hydropower dams — some of Michigan’s biggest river impoundments — after concluding that the miniscule power they provide is no longer worth the maintenance costs.

And applications last year for state grants to help cover the cost of dam repair and removal more than tripled the $15.3 million in available funds.

Often, landowners who seek those funds are more worried about costs and liability than environmental impacts. It’s still welcome news to natural resources officials and fish advocates who have long favored dam removal as a way to cool rivers before climate change warms them beyond repair.

Climate-driven warming is already evident in Michigan’s rivers, said Matt Diana, a DNR fisheries biologist in southwest Michigan.

“We’re seeing things like two-to-three-degree increases in water temperature, pretty commonly,” he said.

The harm of that warming is expected to be most acute for coldwater fish like trout and salmon, which prefer temperatures well below 70 degrees. There are about 10,000 miles of cold water streams in Michigan. But a 2016 study estimated that the vast majority will become too warm to qualify by midcentury, endangering fish species.

Beyond raising temperatures, dams make it impossible for fish to migrate into rivers’ upper reaches where the water tends to be naturally cooler, said Dana Infante, a Michigan State University professor who researches rivers.

“They can’t escape from the stress,” Infante said.

Warm, stagnant water is also more prone to algae blooms, which are at best a nuisance and can sometimes be toxic to humans, pets and wildlife.

More money, more demand

Despite the benefits, public money for dam removal has historically averaged no more than a few million a year in Michigan. Some years, it’s enough to complete just two projects.

But Michigan is picking up the pace after a recent influx of state and federal funding.

In the wake of the Edenville Dam failures of 2020, the legislature allocated about $28 million in new money to EGLE for dam removals and repairs. The state also recently won a $5 million federal grant that will enable 27 dam removals in the coming years. And the federal government plans to award $733 million nationwide to hasten dam repairs and removals over the next five years.

It’s more money than Michigan has ever had to address its problem dams, said Trumble, the state dam safety supervisor. But “I think there’s demand for hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Money isn’t the only barrier to faster action, said Bryan Burroughs, executive director of Michigan Trout Unlimited.

He complained that an overly-tedious dam removal permitting process is sucking up time and money, turning even the simplest removals into expensive undertakings. And he said Michigan needs to get more strategic, ranking dams across the state according to their removal potential, rather than passively inviting grant proposals from dam owners.

“We can’t have these brought to us by accident,” Burroughs said. “We really have to find these high-value, low-cost projects and start dozens of them a year.”

State officials agree with Burroughs’ assessment about the need to prioritize. They’re starting with the hundreds of dams under the state’s control.

The Michigan Department of Natural resources, which owns more than 200 dams, is evaluating them as it decides which ones to keep or remove. Castle said it would cost the state $900,000 annually to keep maintaining the impoundments, even though some of them do more environmental harm than good.

“It’s not a good situation to be in,” she said.

On Swan Creek, a Kalamazoo River tributary west of Allegan, an 86-year-old dam stops the water in what would otherwise be considered a relatively healthy trout stream, and warms the temperature by 10 degrees in the height of the summer. The state is planning to remove the dam in hopes of giving the fish a boost. (David J. Ruck, Great Lakes Outreach Media for Great Lakes Now)

One example is the Swan Creek Dam, on a Kalamazoo River tributary near Allegan. Originally built for recreation, the 86-year-old dam is a death sentence for the creek’s trout.

“In the summer, the river is 10 degrees warmer downstream of the dam than upstream,” Diana said. The agency stocks trout in the creek, but a recent survey found none surviving in the overheated waters below the dam.

It’s one of several southwest Michigan dams that the DNR now hopes to remove. Just upstream on the mainstem Kalamazoo River, a 2018 dam removal provides an example of what to expect.

The former Otsego Township Dam was “a nightmare” for area anglers, said Ryan Baker, who lives in the area. It was risky to portage around it, and the river downstream was mostly lifeless.

Western Michigan University students monitor fish populations in the Kalamazoo River. Five years after the Otsego Township Dam’s removal, healthier fish populations have returned to a once-degraded section of the river. (David J. Ruck, Great Lakes Outreach Media for Great Lakes Now)

Now, he said, “it’s beautiful. There’s actually fish, and places for them to spawn.”

Controversy looms

But while popular with some anglers, the prospect of demolishing the structures can be controversial. In some cases, the reservoirs have become valued recreational lakes that neighbors want to keep around.

While dams damage rivers, they often create new ecosystems for warmer-water fish like bass, along with recreational lakes popular for boating and swimming.

After the DNR announced in January that it was seeking funding to remove the Cornwall Flooding dam, a high-hazard impoundment in Cheboygan County, neighbors organized in opposition to the loss of a beloved warm-water fishing lake. DNR officials now say they’re unsure whether they’ll repair or remove the structure.

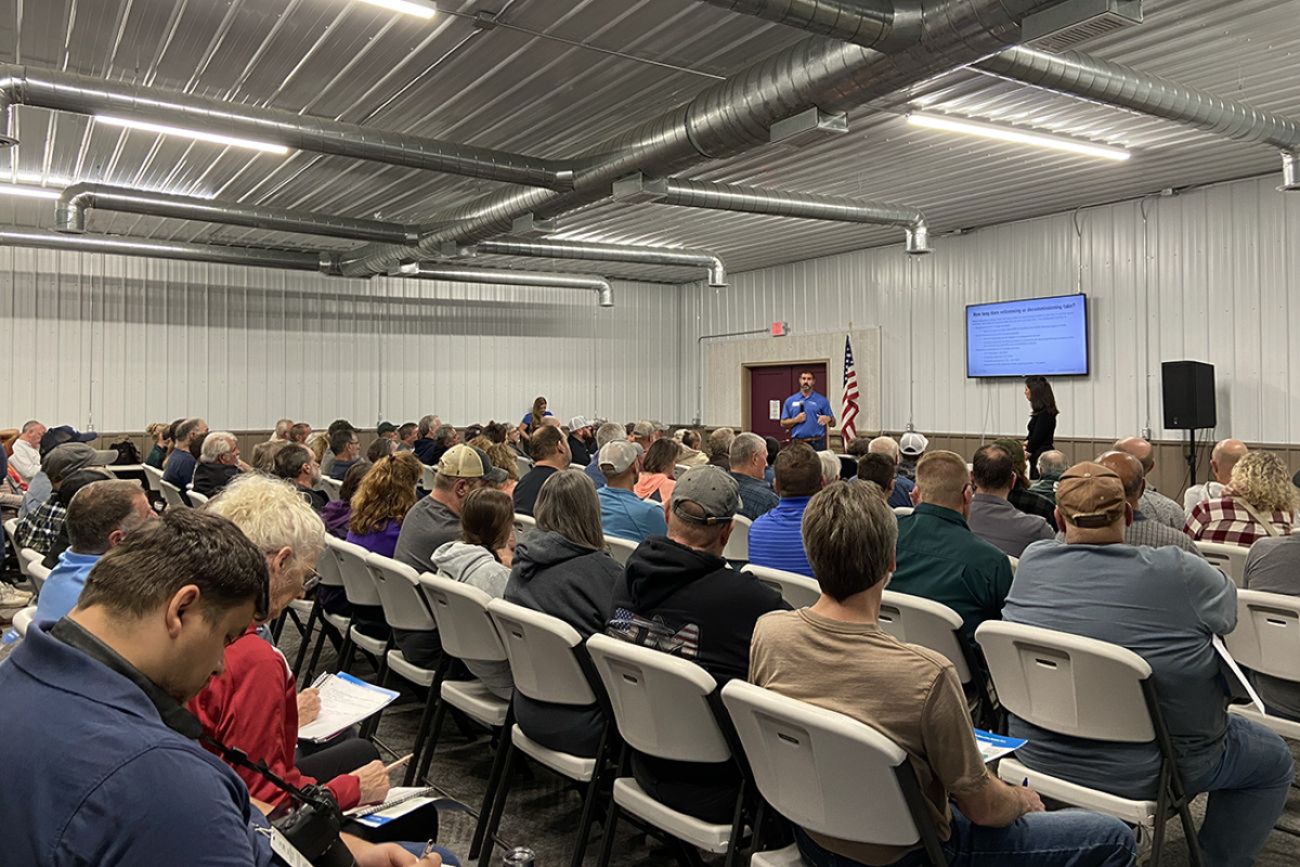

Similar tensions are cropping up across the state as Consumers Energy considers whether to keep, sell or demolish its 13 dams. Public meetings on the topic have been packed with nearby residents urging the company to not to breach the impoundments.

The prospect of dam removal can be controversial for nearby communities that have grown to value the reservoirs created by the structures. As Consumers Energy ponders the future of its 13 dams, large crowds have attended meetings sponsored by the utility to voice support for the dams. (Bridge photo by Kelly House)

The reservoirs created by dams can be a local economic driver, raising property values for landowners who live along the shore and bringing lake-based tourism to the local community.

Removing a Consumers impoundment on the Au Sable might make the river a better place to fish, James McCormick, a nearby township supervisor, told me last year as the company began pondering its dams, “but there wouldn’t be anybody around here to fish it.”

For Consumers, it’s about money. The dams, which average 105 years old, cost more to operate than the value of the small amount of electricity they provide. The company estimates that keeping them around would cost $781 million more than removing them.

Environmental regulators and river advocates see another drawback to the dams: Several of the dams have warmed rivers so badly, they violate Michigan water quality standards and render the downstream rivers incapable of sustaining healthy coldwater fish populations. Climate change will only make things worse.

Consumers is still months away from a decision as it tries to balance its financial realities with the dams’ impacts, both good and bad. The company has told concerned neighbors that if they want to keep the dams around, Consumers wants to help them come up with a way to pay for it. But they’ve also made it clear that Consumers is unwilling to shoulder the cost.

Plans to keep dams that are warming rivers would likely face resistance from environmental advocates.

“We’re in a hurry,” Burroughs said, “to try to save some of our rivers before the new challenges of today stress them out beyond repair.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Workers needed to fulfill America’s infrastructure goals

What are wetlands for, anyway?

Featured image: Matt Diana, a biologist with the Michigan DNR, stands in front of the Swan Creek Dam, an impoundment on a Kalamazoo River tributary that’s slated for removal. State officials say the dam warms the creek’s water by 10 degrees. (David J. Ruck, Great Lakes Outreach Media for Great Lakes Now)