Editor’s Note: “Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A direct descendant of the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe, she lives and works in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her two books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and she is at work on a children’s story. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwe, and these features explore the intersection of Indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

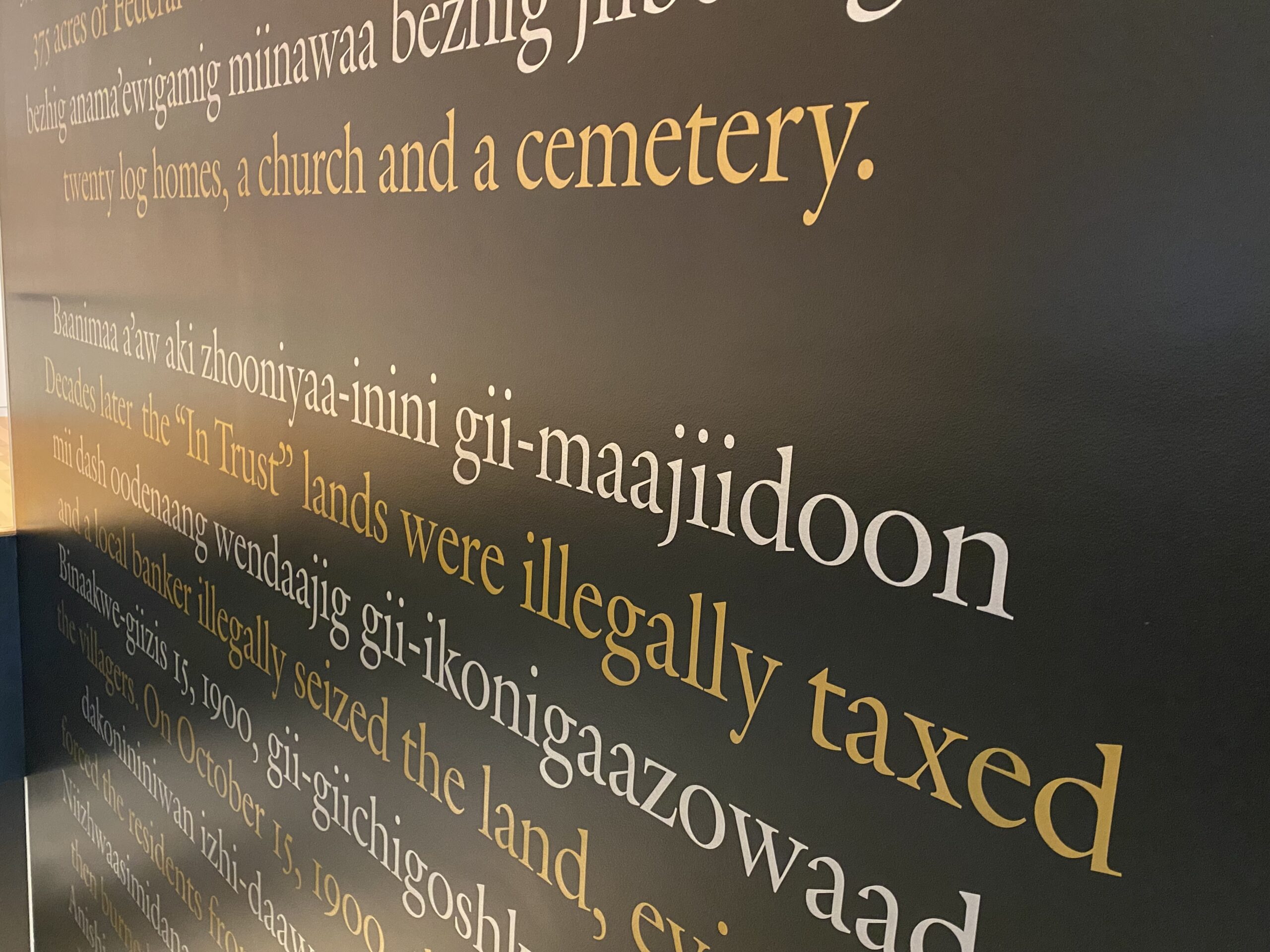

On the rainy night of Oct. 15, 1900, the adults, children and elders of the Cheboiganing Band of Ottawa and Chippewa were forced out of their beds and made to watch as their houses were doused with kerosene and burned to the ground. Only the Catholic church was spared from ruin.

Suddenly homeless, the people walked 35 miles in the rain from Cheboigan (Burt) Lake to Cross Village, in northern Michigan. Also called the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa, this once federally recognized nation continues to fight for justice as they seek federal re-affirmation of their tribal status, a legal battle which began in 1935.

The Burt Lake Band’s struggle to overcome the violent loss of their homelands starting with 1836 Treaty of Washington through today is the subject of Andrea Carlson’s multi-media exhibit at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor. A Grand Portage Ojibwe direct descendant, Andrea confronts the violent history of Burt Lake through works large and small, including expansive “portals,” which invite the viewer to travel through time, from gallery walls to the beach on Burt Lake. I asked Andrea about her decision to work on such a large scale and why that was important to her.

Future Cache. (Photo Credit: Staci Lola Drouillard)

Often, we relate the scale of things against the scales of our own bodies. We have an ergonomic sympathy with the scale of objects. When things are carriable, when we can measure or hold them in the span of our arms, we may feel like we can protect those things, or worse, possess them. Small works make intimacy an imperative. All of that is just to say, scale is so meaningful.

I wanted to make some works large so they could be seen as doors, not windows. I wanted to make works that are larger than human bodies, because I wanted them to overwhelm or extend beyond our outstretched bodies. The large works become backdrops for a human in the gallery space or inoperable portals to Burt Lake. In fact, “Chaboiganing” means a channel or passage between two points in the Ojibwe language.

As an artist who grew up on Lake Superior, I wondered how Andrea found herself inside the story of Burt Lake and what she sees as the common threads between the Cheboigan Band and other Ojibwe people. Her answer begins at Isle Royale, part of the traditional homelands of the Grand Portage Ojibwe.

Sometimes non-Native Minnesotans comment that Isle Royale should be part of Minnesota, not Michigan. The island belongs to Grand Portage Ojibwe people no matter what state name is printed on the map. Before I had known about Burt Lake Band and their history, I had been explaining what I understand about Isle Royale to University of Michigan professor, Andrew Herscher, who is one of the co-founders of the Settler Colonial Cities Project. Herscher is interested in the “Land Back” movement and it was in this conversation that I learned about the Burt Lake Burnout. He told me that UMAA had a bio station on this unceded land and that the university had agreed to making some commitments to the people of Burt Lake, albeit short of “Land Back.”

Artist Andrea Carlson. (Photo courtesy of Andrea Carlson)

Andrea sees the fight for federal re-recognition as part of the multi-pronged attack on the existence of Indigenous people, who are often asked to prove identity through the inconsistent measures of blood quantum.

The Burnout history is not only of violent displacement and removal as a historic event, but a perpetual erasure because they are still seeking federal re-recognition. Their current struggle for federal re-recognition has exhausted Band members, but they have this joy too. Their humility and kindness is very beautiful. I’m seeking the joy part, but I relate to Burt Lake Band member’s exhaustion as a Grand Portage Ojibwe first-generation, direct descendant. So many qualifiers on my identity seem to work towards reducing my sense of belonging. Members of various Native nations aren’t all held to consistent requirements for enrollment. I often see mean folks online fighting those who don’t have enough recorded “Native blood” to enroll, and they characterize descendants as ignorant people looking to profit from being Native. There are those who aren’t Native who wrongfully claim it, but descendants aren’t doing that. I only mention these ideas, because I think I relate to the heartbreak of Burt Lake members even though their situation has nothing to do with blood quantum. I’ve been sitting with these emotions around recognition for a long time which must have given me the confidence or ability to make the work for this exhibition.

“Future Cache” serves as a metaphor for the survival of the people and derives from the existence of actual storage pits once used to store food and other goods. As Andrea explains, her intention is both to move beyond the past, while seizing this opportunity to shape and envision a new future.

Between Burt Lake and Douglas Lake there are hundreds of small shallow pits that were used to store goods. Scientists have done some infrared imaging of the land that has produced some detailed maps that document these caches all over the area. When coming up with both the title and guiding metaphor for the exhibition, I was thinking of the things we do today to set ourselves up for the future, and for survival. These caches are how the ancestors insulated and insured their future, but what are we doing now to insure our futures as a people? I also wanted to move beyond the Burnout history. One of the images in the exhibition states, “Oct. 15, 1900 is not the end,” meaning that the land can be returned, the people can come home because the end has not been written.

Future Cache can be viewed at UMMA from June 11, 2022 through June 2024. (Photo Credit: Staci Lola Drouillard)

I met Band members beforehand to look at the exhibition and I shared some of my artistic decisions. One piece has stars in it, and I explained that I had found a computer program online where you could enter any time, dates, and location and it would show you what stars and constellations were overhead. I wanted to see what the sky looked like during the Burnout. It was raining that pre-dawn morning of October 15, 1900 and survivors had to sit on their luggage to try to keep it dry while they watched their homes being burned. I don’t know if they looked to the sky. I talked about the stars to a few of the members and I saw the tears well up, and I cried too. I’ve never cried talking about my work before. They told me that the stars are so bright on Burt Lake, that there is very little light pollution, and that their ancestors would have seen them.

Another visual element created by Carlson is the graphic depiction of a “sash for carrying things that no longer exist.” I asked the artist what that symbolism carries for her, and in her answer, she also reveals the complications of working on paper, as it relates to the history of Indigenous land treaties and the often duplicitous methods used by white settlers to acquire Native homelands.

I imagine the Burt Lake Band ancestors carrying things, as so many nations of displaced people had. After the Burnout, Burt Lake members had to walk to neighboring Anishinaabe communities seeking shelter. The Burt Lake Burnout is a history like The Trail of Death, The Long Walk to Bosque Redondo, and the Trail of Tears. These are all violent portages.

We typically associate L’Assomption sashes with the Metis people, or the French fur trade. They were used to hold up your pants, but often were used to carry our things by strapping them to our bodies. Generally speaking, we have lost so much, and there is a rightful fear amongst Indigenous people of losing everything: our languages, knowledge, land, families. Some of the things that are most precious to us might also be abstract, and how would you carry them? How would you carry federal recognition? How would you tie a sash around these abstractions? The work is also two-dimensional and on paper—I’m playing with the irony of what a painting does, or how it functions. Paper as a context has its own associations because it has taken so much away from Native people in terms of deeds and contracts about land. I’m using it as a Band-Aid. I’m using paper to make abstract imagery to heal feelings of loss, and using it to make the vessels to carry those things that no longer exist.

The Burt Lake website confirms that the Band “continues to exist as a distinct Tribal entity and has never been terminated by the United States Congress.” The Band has again appealed the most recent federal determination, in which the Bureau of Indian Affairs denied their request for re-recognition. With 320 enrolled members, federal recognition would give authority to form a tribal government, gain the right to exercise legal jurisdiction and allow enrollees access to federal funds, medical care and other services. The Band is recognized by the state of Michigan, but that designation comes with no access to services or benefits.

“Future Cache” does the breathtaking work of bridging the harmful history of Burt Lake with current efforts towards upholding tribal sovereignty and Indigenous language and culture revitalization—something we are seeing all across Turtle Island. The show is on view through June 2024. https://umma.umich.edu/exhibitions/2022/andrea-carlson-future-cache

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Nibi Chronicles: We are still here, and so is great grandma’s lilac

Nibi Chronicles: Restoring what was lost in translation, one place name at a time

Featured image: 40-foot-tall memorial wall to the Cheboiganing Band of Ottawa and Chippewa. (Photo Credit: Staci Lola Drouillard)