I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

It was, admittedly, not my finest hour.

Searing pain raced up my nose and flooded my eyes with tears. An instant later, the silicone rim of my mask lost contact with my upper lip allowing water to gush in and straight up my nose.

A flooded mask was mildly annoying but nothing to panic over. However the intense pain radiating across my face definitely had the potential to induce panic. Lord, it hurt.

The diaphragm on my regulator vibrated loudly as I drew in a deep quivering breath. Unfortunately for me, my best option was to breathe deep and wait it out.

I just prayed that the crayfish currently latched onto the end of my nose didn’t stay there much longer. If it did, I was gonna need to shop for a nose ring after this dive.

My overly-forceful exhalation of bubbles failed to dislodge the crayfish.

The diaphragms in my reg and in my gut fluttered in unison.

How could I have been so stupid? Why didn’t I realize how flawed this idea was before proceeding? Thoroughly harass a crayfish and then hold it close to your face. Sure, what could possibly go wrong?

Skip the Etouffee

Crawdad, crawfish, or mudbug — a crayfish by any other name is still basically a miniature lobster. And a popular menu item in the Southern United States. Having attended one crawfish boil in my life, I would have to be starving and genuinely desperate to attend another.

As with lobster, a lot of people savor crayfish tail meat.

But unlike a lobster tail which provides enough sustenance to be considered a main course, a single crayfish tail is about the equivalent of eating one grape. Which is why crawdads are often served by the pail.

I think it’s telling that when articles and websites mention the decline in crayfish populations, they typically attribute it to habitat loss and invasive species but they rarely point to all the backyard buckets filled to the brim. I find the volume of animals killed per serving completely unappetizing and unnecessarily wasteful.

Crayfish themselves are both predators and prey.

They love a good fish-egg breakfast followed by mayflies for lunch. They might snack on scuds in the afternoon before heading back to their den where the chunk of fish carcass they stashed yesterday would be ripe and ready for supper.

While out of their den, crayfish are ever vigilant, as predators abound. Smallmouth bass particularly enjoy crayfish for breakfast, lunch, dinner and snack time.

Bass eating crayfish. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Cool crustaceans

Ever walked across a mowed lawn in an urban subdivision and seen a very small hole surrounded by tiny mounds of dirt?

I always found them intriguing and even more so when I learned the holes were made by crayfish. It seemed highly improbable given the nearest body of water was usually miles away. Except there was enough water nearby, beneath my feet.

Primary burrowing crayfish spend most of their lives under fields, ditches, prairies and wet meadows. They build and live in deep subterranean tunnel systems that go at least as deep as the ground water table.

These burrowers can live upwards of 20 years and according to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, primary burrowing crayfish are a good food source for animals and help aerate soil.

Secondary burrowers will go underground to escape drought, cold temperatures and predation. But their underground burrows are less complex and their burrows may or may not have chimneys or piles of mud around them. Most secondary burrowers live only a short distance from permanent bodies of water such as streams and ponds.

The crayfish attached to my nose was a tertiary burrower.

Tertiary burrowers rarely, if ever, leave water and will only do so during extreme circumstances. They do their burrowing underwater. They typically excavate small caves under rocks and logs.

As both predators and prey, crayfish are important keystone species in the Great Lakes.

Crayfish also have the unique behavior of carrying their eggs and larvae under their tails. Makes sense. How better to keep them safe than being tucked under their mother’s tail?

The eggs hatch as identical, transparent versions of the adults. But so tiny they could stand on the head of a pin. The minuscule larvae continue to hide under their mom’s tail for a couple more of weeks.

Female crayfish carrying babies. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Ethical review

The ethics behind nature photography, including filming underwater continues to evolve.

In the past, every professional underwater shooter had images of inflated puffer fish in their portfolios. Puffers live around coral reefs and they are covered with sharp spikes. When threatened a puffer can inflate their bodies into a round spiked ball which is very hard to swallow. It looks cool so some divers began grabbing, squeezing and otherwise harassing puffers just to make them inflate.

Today, credible editors would never publish those images. Even if the behavior occurred naturally and was not forced, showcasing a puffed puffer fish just promotes harassment.

One of the hot topics in underwater ethics centers around diver and marine life interactions. The generally held rule is don’t. Don’t touch anything. Don’t damage anything. Don’t injure anything. Don’t harass anything. Don’t feed anything.

While this might seem excessive, there is sound reasoning behind each directive.

Most divers dive in the ocean. And most recreational diving is done on or near coral reefs where it only takes one carelessly placed hand or knee to damage or injure a delicate marine organism. So, a hands-off approach really is best for all.

A carelessly placed hand in freshwater is more likely to injure the diver via a snagged fishing lure or razor sharp zebra mussel shells. So, whether in saltwater or freshwater, we’re always cautious of where we put our hands and knees.

Harassment takes many forms. Forcing an animal to inflate or squirt ink or otherwise exhibit defend behaviors is textbook harassment. As is diving around whales, petting manatees or touching sea turtles.

Many locations have taken to limiting the total number of divers allowed to visit a site each day to reduce the impact on local ecosystems.

I’m a firm believer that it’s not ok to freak out another creature — even if it is just a crawdad. Sadly, the proof of my failing was still driving the point home on the end of my nose.

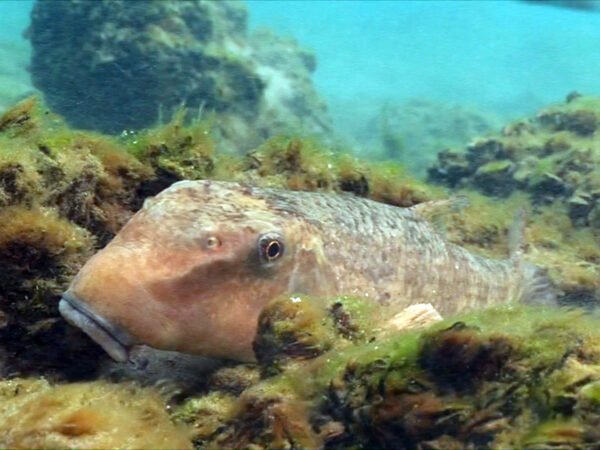

Adult crayfish. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Just Deserts

As an underwater model, I’m often called upon to position myself with the subject of the photoshoot between me and the camera lens.

Having a diver in-frame is one of the easiest ways to show scale. A school of emerald shiners on a clear summer day makes a pretty picture. But adding a diver silhouetted in the distance allows viewers to better gauge the impressive size of the school.

Holding small creatures up to my face was another technique for showing scale and something I used to do — emphasis on the past tense.

Initially, I had picked up the crayfish and held it at arm’s length towards the camera. If you know how to hold a crayfish, they are quite harmless. But with each shot the camera moved steadily closer and I gradually brought the crayfish closer and closer to my face.

It never occurred to me that it might latch onto my nose.

It was an act of pure desperation by the crayfish with only a 1 in 100 chance of it landing a perfect blow. Too bad for me, the odds were in its favor that day. Even as my eyes watered and my face throbbed, I held no malice towards the crayfish.

If a giant picked me up by my ponytail, I’d lash out too.

It was a pain-filled lesson in not mistreating others. A significant life lesson driven home by a 4-inch crayfish.

Thankfully, I was aware that like many venomous snakes, once a crayfish latches on, the worst thing to do is try to pull it off as this typically only causes them to squeeze tighter.

Any hope of assistance from my buddy had already vaporized behind a wall of bubbles. As soon as the crayfish grabbed my nose, Greg began laughing so hard he drained half his tank.

Eventually, the crayfish would let go. Until then, all I could do was eat my just deserts.

Yeah, definitely not my finest hour.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Searching for the elusive sculpin

I Speak for the Fish – What’s the most popular freshwater fish?

Featured image: Crayfish latched onto, contributor, Kathy Johnson’s nose. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

2 Comments

-

I really like this blog! You’re a very good writer Kathy and I love aquatic life.

-

Kathy Johnson, I have studied crayfish for over 50 years and this is the best popular article about crayfish I have ever read (I haven’t read them all but …). I am interested in where the encounter took place. The crayfish in the lead photo is a Cambarus robustus, Bib Water Crayfish. In the Great Lakes they are found in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. I am not aware of records for Lake Huron and Lake Michigan but I suspect they are there, maybe even Lake Superior but that getting out there a ways. Can you let me know the approximate locality of your encounter? I am assuming it was in one of the Lakes.