This article was republished here with permission from Great Lakes Echo.

By Jack Armstrong, Great Lakes Echo

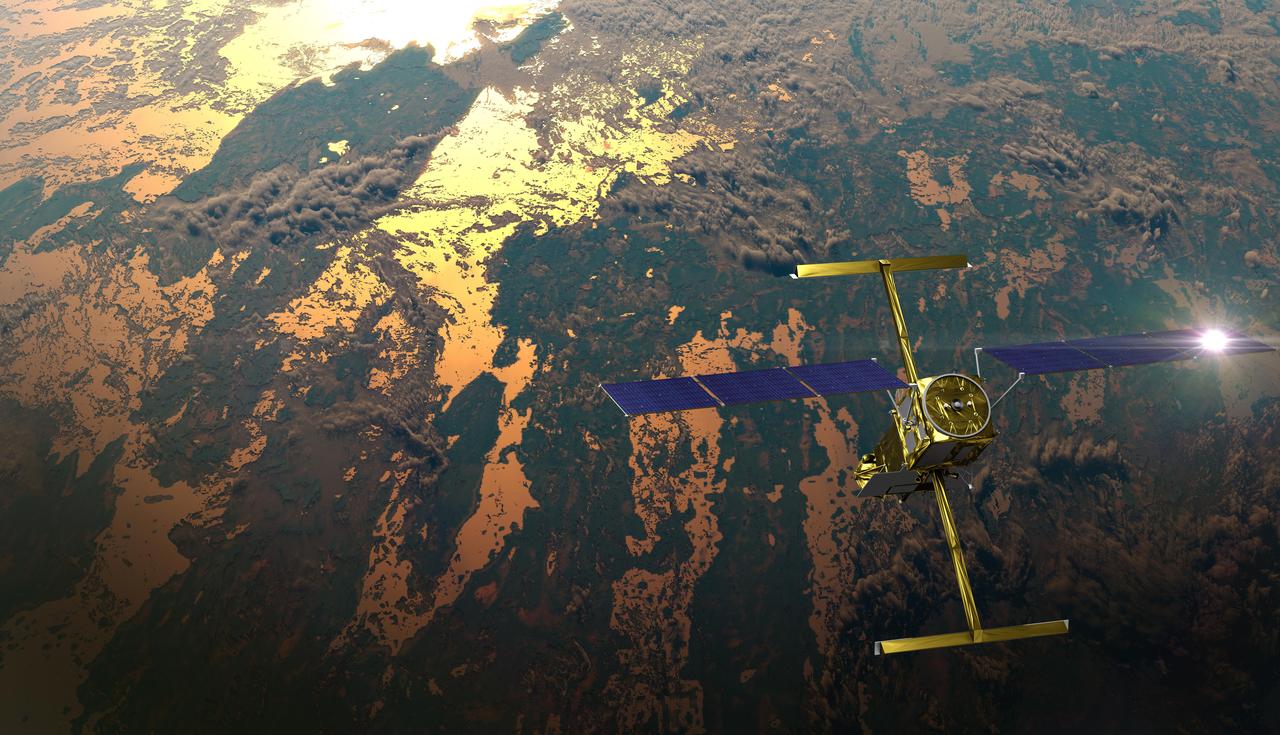

NASA’s new satellite is a huge upgrade for measuring Earth’s surface water that could help scientists. It’s like swapping out your old iPhone for a new model with a better camera, and it could help us better understand the Great Lakes.

The Surface Water and Ocean Topography, SWOT for short, is about the size of an SUV and carries an array of instruments to measure surface water.

The product of a more-than-20-year collaboration between NASA and France’s Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, the satellite was launched last December. It will measure surface currents and the height of water in Earth’s lakes, rivers, oceans and reservoirs. It’s the first mission to observe nearly all the water on the Earth’s surface.

This data, slated to be public this summer, will help scientists better understand the Midwest’s greatest natural resource.

“The things that we haven’t been able to measure in the Great Lakes, we might be able to measure now with the higher resolution,” said Sam Kelly, an associate professor at the University of Minnesota Duluth and a member of SWOT’s science team.

The SWOT satellite is about the size of an SUV. ( Photo courtesy of NASA Image and Video Library)

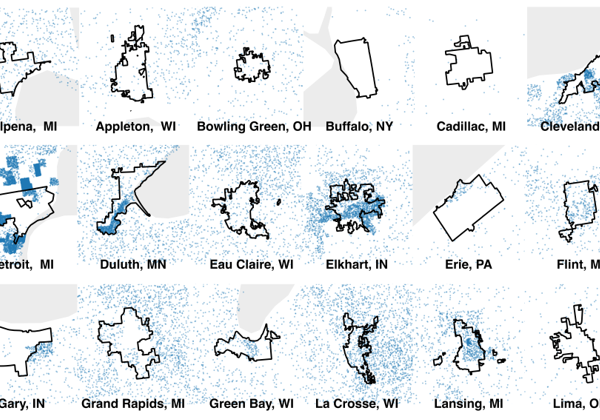

The extremely high clarity of the satellite allows it to collect data on small water features like fronts and eddies that previous instruments couldn’t detect. Right now, scientists and engineers are slowly turning on SWOT’s instruments, making sure everything works correctly, and taking preliminary data.

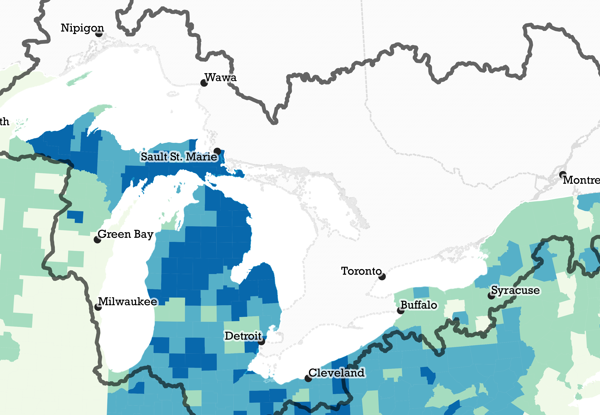

Understanding our water is useful for many reasons. Measuring water levels helps keep track of flood hazards and study the effects of climate change. Mapping currents allows scientists to understand the path pollution takes and maximize the efficiency of boats and vessels.

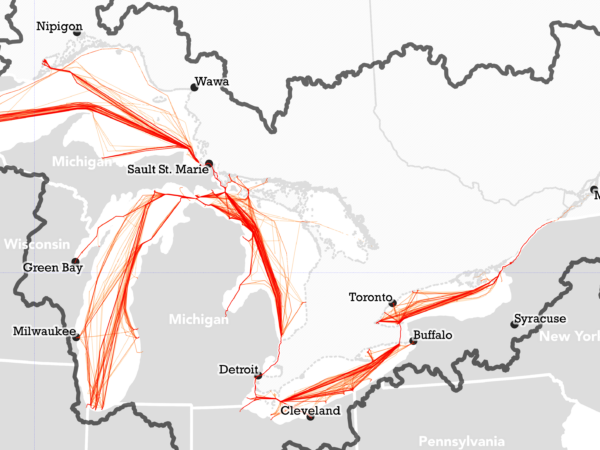

But models and measurements of the Great Lakes are not as detailed as scientists would like them to be. A lot of our knowledge on Great Lakes currents comes from a forecast system that simulates lake conditions in real time, said Dan Titze, a physical scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. This simulation is supplemented by a handful of underwater current-sensing devices. But the sensors can only provide data for currents where they are located, and the forecast model needs real-world observations to affirm and improve its measurements.

The SWOT satellite awaits launch last December at Vandenberg Space Force Base. (Photo courtesy of NASA Image and Video Library)

“Having better information on currents from a program like this would give us more information to validate our models and determine where we could make additional improvements,” Titze said.

Satellites have measured water levels since the early 90s, Kelly said. But these satellites only measure the water directly underneath them.

“You get one line and only a few of those lines cross the Great Lakes,” Kelly said.

SWOT will change that. The craft will measure about half a lake in one crossing with a 62.13 mile swath (just over half the size of Lake Michigan) and will map currents with a resolution five times higher than present devices do, he said. The satellite will produce about a terabyte of data every day.

Tahani Amer, the program executive for the SWOT mission, compared the upgrade to SWOT to the James Webb Space Telescope replacing the Hubble Space Telescope.

SWOT will also aid researchers studying the coastal effects of climate change and how the oceans absorb carbon, allow us to assess our global water inventory, and help communities predict and be better prepared for floods and droughts.

“It is endless possibility to help everybody on planet Earth,” Tahani said.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Michigan’s Magnet Man attracts river trash

Artificial reefs bring wild lake trout to Lake Huron

Featured image: An illustration of the SWOT satellite orbiting Earth. NASA planned a 3-year-mission for the craft, but hopes to collect data for longer. (Photo courtesy of NASA Image and Video Library)