I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

When your dive buddy is a professional underwater cameraman, it is not unusual to spend 30 minutes, 45 minutes or even an entire hour-long dive in one spot without moving.

More often than not it is reproductive behaviors that keep us glued in place. Courtship rituals, nest building and nest guarding are all guaranteed to lock us down.

Unlike my partner, my mind is not occupied with exposure adjustments, image composition or spot focusing. And because my assistance is rarely needed for filming, I tend to let my eyes wander even if my body can’t.

One of my favorite pastimes is playing spot-the-sculpin.

Looking for sculpin is similar to playing a hidden-object app or perusing a Where’s Waldo book. With an average length of only three inches, camo coloring and a penchant for hiding, sculpin are worthy opponents at hide-and-seek.

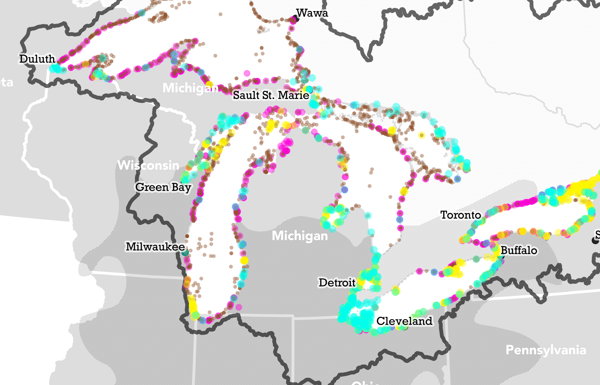

There are 300 known species of sculpin worldwide but only four are found in the Great Lakes. Deepwater, mottled, slimy and spoonhead sculpin are all native to the Great Lakes but the majority of us will never encounter one.

In the Depths

Sculpin are dedicated bottom-dwellers. They have no swim bladders but unlike bladderless round gobies who constantly pop up off the bottom, sculpin prefer their bellies never lose contact with the rocks.

They feed on aquatic insect larva, worms and small crustaceans. The sculpin’s lower jaw has tiny nerve endings that can detect vibrations from prey buried in the bottom.

Deepwater sculpin are aptly named as they are generally found below 60 feet and have even been documented more than 1300 feet deep in Lake Superior.

Personally, I’ve been over 100 feet deep in Lake Huron and Ontario and to 175 feet in Lake Superior but I’ve yet to meet a deepwater sculpin.

Once abundant in Lake Ontario, the deepwater sculpin nearly disappeared and were thought to be extinct for 25 years until being rediscovered in 1996.

The preference of deepwater sculpin for extreme depths makes it very difficult for researchers to study them. Often the only way to confirm the presence of deepwater sculpin is by stomach-content surveys of deepwater predators like burbot and lake trout.

Spoonhead sculpin are as elusive as the deepwater variety. Spoonheads are no longer found in Lake Erie and Lake Ontario but small populations may still remain in parts of the Great Lakes.

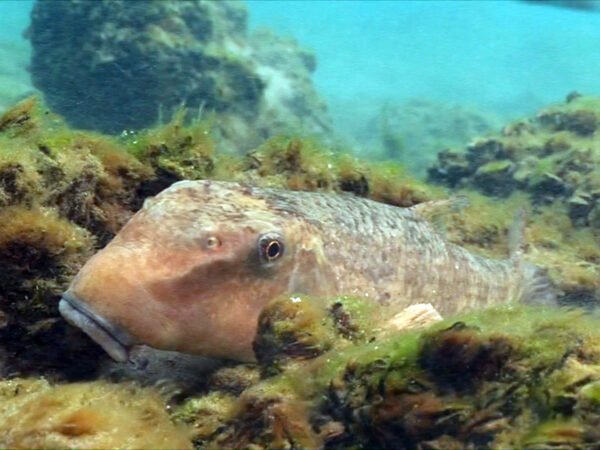

Sculpin Bass. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Camo Kings

In the Lake Huron to Lake Erie area, we mostly see mottled sculpin although it is very difficult to distinguish between mottled and slimy. The two species are so similar that they often hybridize and the hybrids basically require an ichthyologist to identify them.

Mottled sculpins (Cottus bairdii) are named for Spencer F. Baird (1823-1887) the first United States Fish Commissioner and the majority of sculpins surveyed by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources in the Huron-Erie waterway have been mottled.

Sculpins have smooth scaleless bodies. The mottled have a cream colored belly, dark brown saddle patches and tan to chocolate brown splotches camouflaging their bodies, head, and even their fins.

Sculpins have large flat heads which is how they earned the moniker miller’s thumbs.

In days gone by, millers would occasionally cheat their customers by placing their thumb on the scale to increase the weight and, thereby, the customer’s bill. Savvy customers learned to keep an eye on the miller’s plump thumbs.

I imagine at some point, someone standing on a fishing pier said, “Those fish look like my miller’s thumb.” And the nickname stuck.

Sculpin camouflaging. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Don’t Move

One of the unique things about sculpin is that they remain completely motionless when disturbed.

Most fish dart away when their shelter gets dislodged. Not sculpin. They don’t move a fin. It’s an effective defense strategy and their best option given they have no chance of outmaneuvering a trout, bass or similarly skilled predator.

Instead of bolting away, sculpin rely on their blotchy-brown coloration to blend into the river bottom, like donning a cloak of invisibility.

Smallmouth bass often hover right beside me hoping I will dislodge objects on the bottom. Their goal is to capture whatever pops out. Crayfish, catfish, darter, goby, anything that tries to make a run for it is gonna have a bass right on their… ass.

Another effective survival strategy sculpin employ is sharing shelter space with other species. If the shelter is compromised, the sculpin can almost bank on the other species bolting away and taking the predators with them.

If sculpins are alone, their cloak of invisibility and commitment to motionlessness is often enough. I find bass are not overly patient and with no obvious prey in sight they generally back away from me until I dislodge another rock. But only after re-covering the sculpin I spotted and the bass missed.

Sculpin hiding. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Standing Guard

Sculpin are nest guarders.

The male picks the nest site then lures the females in with courtship displays that include head shakes, swelling of their gill covers and drumming sounds made by slapping their fins on the bottom.

The female turns upside-down to deposit a single layer of eggs on the ceiling of the nest site and then leaves. For the next two weeks, the male will continuously fan the eggs with his pectoral fins to aerate them and keep them free of silt.

The male will also defend the eggs against predators like crayfish and logperch.

After about 14 days, the eggs hatch and the fry drop to the bottom of the nest site where the male will continue to guard them for another week until they can absorb their yolk sacs and gain enough strength to venture out on their own.

Sculpins do not produce a lot of offspring each year. Rather, they invest a lot of energy and effort into rearing a small batch. And securing a good nest site is critical to their success.

Sculpin. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Housing Crisis

Before the arrival of round gobies, I could find a mottled sculpin under most rocks I checked.

The round goby’s impact on sculpin was threefold. Predation on sculpin eggs. Predation on sculpin young. And direct competition for nesting sites.

Gobies are also nest guarders. They prefer the exact same type of nest site and they are far more aggressive than sculpin.

The gobies took all the really good nest sites and left the hard to defend sites to the sculpin which further compromised their ability to reproduce successfully.

These days I have to check a lot of rocks before I find a sculpin. But then, my search area is usually limited.

I can never allow my attention to drift too far away from my cameraman-buddy.

While that might seem like an easy task given his sculpin-like tendency towards stillness. The paradox is that he might not move at all for 47 minutes and then suddenly dart away faster than a muskie after a walleye.

If a cormorant zooms past. A soft shell turtle meanders by. Or a steelhead suddenly appears. My buddy is quite likely to depart with them. Which is why I always need to be prepared to quickly switch from playing hide-and-seek to follow-the-leader.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish – What’s the most popular freshwater fish?

I Speak for the Fish: Eyeballing Walleye

Featured image: The elusive sculpin fish. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)