Editor’s Note: “Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A direct descendant of the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe, she lives and works in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her two books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and she is at work on a children’s story. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwe, and these features explore the intersection of indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

The river is posted “Indian Camp Creek” on the trail maps, but the sign at the designated campsite reads “Camp Creek.” This adjustment was made by the Superior Hiking Trail Association, the organization that maintains the 300-mile trail that winds through the Superior Highlands along the North Shore of Lake Superior.

Today the creek is moving right along—the force of gravity pulling in the winter snow melt, spring groundwater and the light rain that covers everything. Conditions are well beyond “babbling,” and closer to “raging.” I was interested in seeing this spot because of the name, and also because my partner Cathy wanted me to see the unique rock formations here—massive, smooth stones that form the creek bed. But today the water is so high, it obscures any view of the stones or riverbed.

The name “Camp Creek” raises questions about the origin of place names and how the lakes, rivers and creeks of Anishiinaabe Akiing—Anishinaabe Land—were often changed or adapted over time. There are a few early maps that tell us what these places were called prior to colonization, but many of the oldest names once known by Indigenous people have been lost or buried.

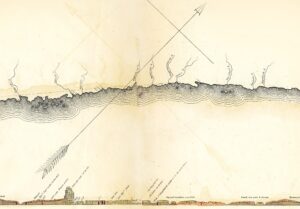

Kurt Mead is the naturalist at Tettegouche State Park in Beaver Bay. The river that runs through the park is known as the “Baptism River,” which comes from the French “Rivière au Baptême.” Several years ago, Jeff Dixon, a geologist friend of Kurt’s picked up a two-volume set of old books by Dr. Joseph Norwood called Geological Map of parts of Minnesota and Wisconsin, designed to show Portions of the Rock Formations now concealed. The set included a very detailed “bird’s eye” view of Lake Superior’s North Shore, complete with technical, geological drawings. The map included many Ojibwe place names from 1848, the year that David Dale Owens and his expedition crew were on the North Shore in search of lead ore and coal. It was an extraordinary find, because the survey and map pre-dated any other written, geological data by several years.

When phonetics are not enough

One of the tricky things about old maps in this part of the world is that the person transcribing them likely used the English language as a reference point. In the case of the Owen Expedition map, the phonetic spelling of the name does not give you the whole picture.

When Kurt began to decode the information, he knew that a speaker of Ojibwemowin was needed to correctly interpret the names, which in many cases are “new” to the canon of Lake Superior history. It took several years for the project to find footing, and last winter Kurt worked with a group of people at Grand Portage to explore the linguistics found on the map.

Miskwaa anang—Erik Redix is the Ojibwe Language and Environmental Education Coordinator for the Grand Portage Band of Chippewa. He paired up with another Ojibwe language teacher, Mike Zimmerman, a UWMilwaukee faculty member to work through the extensive list of place names, which span an area from the Pigeon River in the North (Omimi zibing) to the Nemadji River (Namanjii zibi—Left Hand River) in the southeast, which outlets into Lake Superior at the city of Superior, Wisconsin.

Deciphering phonetically translated words recorded in 1848 requires a deep understanding of how the Ojibwe language is structured, as well as the use of other old maps to compare and contrast the original meaning behind each name. And it turns out that a lot of the early map makers struggled to get it right.

According to Erik, the transcriptions on the Owen map are “. . . the most accurate to other historical resources. There was an Episcopal minister out at White Earth who did a Minnesota Ojibwe place names interpretation. And that guy, Joseph Alexander Gilfillan—his work was published in the late 1800s. So about 40 years after the Owen Expedition. His interpretations are only about three quarters right.”

The Ojibwe language is a beautifully descriptive form of communication, and in every case, the name recorded on the map gives us clues about what it was like, back when the Owen expedition team was navigating through the region in birchbark canoes and speaking with Lake Superior Ojibwe people directly at the source.

Owen map: Baptism River section. (Photo courtesy of Staci Lola Drouillard)

The devil in the details

I asked Erik to share some of the group’s initial findings, and he cited the Fall River as a good example of how the English name is linguistically miles away from the Ojibwe, which is “Oginekan zibi, the place of abundant Rose Hips River.”

Another phenomenon encountered in the uncovering of old names is the influence of missionaries, whose work was focused on converting Indigenous people to the Christian faith, and also converting original place names into something else entirely, in order disrupt the associations Anishinaabe people had with physical locations. Erik’s “go to” example is Devil Track, a well-used inland lake and prominent river that outlets between Grand Portage and Grand Marais.

“If you studied American History, but especially Native American history, you have a familiarity with the fact that not just in Ojibwe country, but throughout the country, missionaries often interpreted any place name, any personal name, that had the word ‘spirit’ in it to ‘devil.’ So, the Devil Track River, Devil Track Lake—the Ojibwe name obviously isn’t [referencing] the devil. Its original name is Manido bimadagakowini zibi, which means, ‘Spirits walking on the Ice River.’ And to me that gives a much richer understanding of that place. It’s just a beautiful name.”

The original name for the Baptism River, the place where Kurt Mead works as an interpreter of the natural world, suffered the same style of conversion. It turns out that the true, original name for the river is “Asin badakide ziibi” which literally translated means, “Standing Rock River.”

Kurt, Erik and the other interpreters are working with the 1854 Treaty Authority to create a map that brings together all of their findings, which they hope will be available this summer in hard copy and online. I asked Kurt why he thought names were important and he said, “We’re on Native land—we’re in the 1854 ceded territory. And I want people to know that. I want people understand that when they’re hiking around, that this place has a history and it has a depth that goes beyond, well, our current culture.”

The Owen expedition did not record the original name for “Indian Camp Creek,” even though it’s noted on the 1848 map. But given what we know about Ojibwemowin, perhaps it was a place where the Lake Superior Anishinaabe set up camp. Or maybe there is another name out there, which describes a place where the water moves over large, smooth stones. In any case, “Camp Creek” leaves out a lot of the story.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Nibi Chronicles: Greeting Old Man Maple during the Sap Boiling Moon

Nibi Chronicles: Acknowledging one family’s knack for finding ancient stone tools

Featured image: Camp Creek (Photo Credit: Staci Lola Drouillard)