In his book “Great Lakes Champions: Grassroots Efforts to Clean Up Polluted Watersheds,” John Hartig looks at how 14 Great Lakes residents are working to restore some of the region’s most degraded areas. While significant challenges remain, there is much to celebrate, including the return of sentinel fish and wildlife species, lower contaminant levels in fish and wildlife populations, and greater public access to these waters.

Hartig, a Great Lakes Now columnist, spoke with Great Lakes Now interim editor Sharon Oosthoek about the book. Here’s an edited version of that conversation:

Great Lakes Now: I understand why you would want to focus on ecosystem success stories, but you don’t shy away from explaining the huge challenges the Great Lakes face. Were you surprised by the ability of any of the champions to beat the odds?

Yes, I was surprised. If you were a betting person, you would not have bet on these champions because of the enormous challenges. In the case of the Buffalo River, floating oil caught fire in 1968. At the time, the river was grossly polluted with industrial and municipal waster, and there were no fish in the lower stretch. Today, you can find 25-30 species of fish, an improved invertebrate community living in sediments, peregrine falcons nesting near the river after a more than 30-year absence, and a community that has rediscovered the lower river for recreation and waterfront redevelopment, attracting hundreds of thousands of people. At the helm has been Jill Jedlicka Spisiak, executive director of the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper.

Hamilton Harbour on Lake Ontario is another good example. It was one of the most polluted areas in the Canadian portion of the Great Lakes. In 1969, a Canadian House of Commons debate described the harbor as “a stinking, rotten quagmire of filth and poisonous waste.” Today, it is a shining example of an ecosystem approach, a Great Lakes leader in habitat restoration, and an international model for contaminated sediment remediation. Nobody thought such improvements were possible in the Steel Capital of Canada – Hamilton, Ontario. But John Hall, a planner by trade and employee of a Conservation Authority, stepped forward to guide stakeholder efforts to cleanup the harbor and expand a conservation ethic throughout watershed communities.

Great Lakes Now: You write about the distinction between environment and ecosystem. Your champions seem to understand the difference too and make good use of it. Can you elaborate a bit?

The difference between environment and ecosystem is like the difference between house and home. A house is external and detached, whereas a home is something we see ourselves in even when not there.

Therefore, we all must recognize that we are part of our ecosystem and what we do to it, we do to ourselves. In addition, we all must work together to care for the watershed we call home. Each of these champions were part of grassroots efforts to use an ecosystem approach to clean up their watershed. These champions helped bring stakeholders together to envision a desired future state of their river or harbor, co-produce knowledge, and co-innovate solutions to restore their aquatic ecosystem.

Great Lakes Now: You note near the end of your book that each of the 14 champions has certain traits in common. What are they and how can we encourage these traits?

Each of the champions share nine traits in common:

- Passion for the Great Lakes and their restoration

- Big dreamer with a compelling vision

- Collaborative team builder

- Eagerness to learn and share knowledge with others

- Practical problem solver

- Action oriented and adaptable

- In it for the long haul

- Honesty and integrity

- A generous servant leader

One of the reasons I wrote this book was to amplify these traits and to pass on the lessons learned to the next generation. These stories, champion traits, and lessons learned must be taught in schools to help inspire the next generation of Great Lakes champions.

Great Lakes Now: Asking you to choose your favorite champion would be like asking you to choose your favorite child, and I’m not going to do that to you. But which champion’s story most resonated with you?

They are all my favorites, but if you were to pin me down, I would say a husband-and-wife team who led restoration of Fox River and Green Bay, Wisconsin. The lower Fox River received discharges from 13 pulp and paper mills – the largest concentration of such industry in the world. These discharges resulted in substantial PCB contamination. Bud and Vicky Harris, from University of Wisconsin-Green Bay and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources respectively, guided the responsible companies, governments, and nongovernmental organizations through a scientific process that resulted in a $1.3 billion cleanup of PCB-contaminated sediments. The Harrises were also instrumental in restoring a chain of islands and associated wetlands called the Cat Island Chain. Critical success factors were sound science-based decision making, inclusive governance for ecosystem-based management, and effective community engagement.

Great Lakes Now: What is the primary take home message from Great Lakes Champions?

The Great Lakes have suffered greatly from human use and abuse since the advent of the fur trade and the agricultural and industrial revolutions. But progress is being made as evidenced in the stories of Great Lakes champions. These champions and the progress in restoring pollution hotspots are signs of hope, not only for those working to restore the Great Lakes but others working to restore degraded watersheds throughout the world.

John Hartig’s book is available online at:

https://msupress.org/9781609177058/great-lakes-champions/

https://www.amazon.com/Great-Lakes-Champions-Grassroots-Watersheds/dp/1611864356

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/great-lakes-champions-john-h-hartig/1141527768

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes Moment: Solving the contaminated sediment remediation funding puzzle

Great Lakes Moment: Decreasing Great Lakes ice cover has consequences

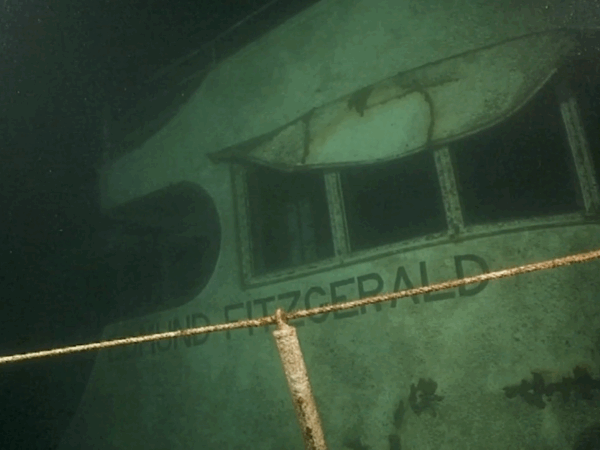

Featured image: Photo courtesy of John Hartig