“Something was clearly wrong with Lake Erie.”

That’s how filmmaker David J. Ruck remembers being inspired to begin working on “The Erie Situation,” a feature-length film that’s been shown at film festivals this year and now will air simultaneously on PBS stations in four states at 9 p.m. ET on Monday Sept. 12.

To see if your station is one of them, click HERE.

In examining the notorious “harmful algae blooms” largely caused by nutrient runoff from agricultural fertilizers, Ruck says he discovered the problem isn’t simply a matter of blaming farmers. And the blooms are not limited to Lake Erie.

“Just this past month we’ve seen alerts for them in more than a dozen states, all over the country,” Ruck says.

Great Lakes Outreach Media’s David Ruck and his dog, Billie.

In advance of the Sept. 12 airing, Great Lakes Now’s Sandra Svoboda interviewed Ruck about his work and the inspiration he takes from the Great Lakes. The interview was conducted via email and edited for clarity and length.

Here is a playlist of Great Lakes Now segments that Ruck worked on:

Great Lakes Now: When did you first realize you wanted to connect your background as a resident of the Great Lakes, someone who grew up here, with your work in documentary and video production?

Ruck: I was first interested in narrative filmmaking. That’s what I started going to school for. When a friend’s aunt, who was working with what is now called Alliance for the Great Lakes approached me about doing a documentary on the Hooker Chemical Company and its toxic legacy in Montague, Michigan (It’s the same company responsible for the Love Canal fiasco.) That’s when I realized I really enjoyed the process of digging for facts and truth and how that journey was transformative.

Environmental storytelling is really the story of how humans interact with the planet. And because I’m so connected to the Great Lakes on many levels, my work has just naturally been drawn to these vast and diverse bodies of water and the people who surround them.

Great Lakes Now: “The Erie Situation” started as what we call a “passion project,” something you work on before there is any outside funding or commitment from a TV station or film festival to show the finished work. What was it about this topic that made it worth it to you to invest yourself like you did?

Ruck: Something was clearly wrong with Lake Erie. My friends at NOAA and LimnoTech were always talking about “the bloom” and so I wanted to learn more. What I discovered was a classic case of what is essentially well-funded industrial entities perpetuating a system that allows for and indeed fuels the impairment of Lake Erie.

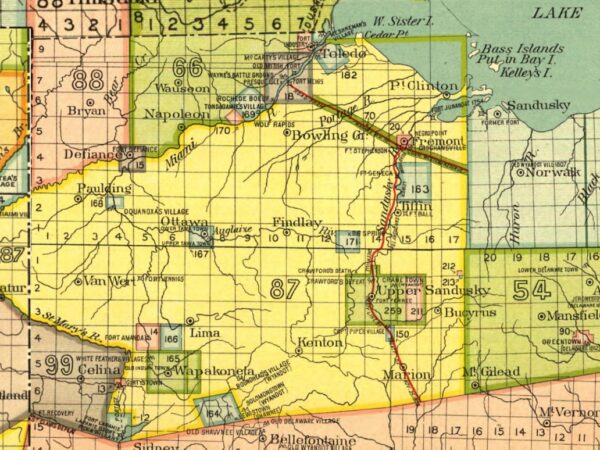

The science of why and how Lake Erie experiences harmful algal blooms on a level that attracts national attention is basically settled: nutrients from high concentrations of industrial agriculture along the Maumee River drive blooms on an annual basis. So what is being done about it? That’s what I wanted to find out. So “The Erie Situation” is really my journey of understanding in certainly what the bloom is and what it can do while it’s there, but it’s also a story about a system that is perpetuating what amounts to Lake Erie being a disposal pit for industrial agricultural runoff. There is a system that enjoys the fact that there is little to no practical oversight with regards to the practices that are driving this runoff. So how do we balance to need to grow healthy food with the need for a healthy water system and environment? And what forces stand in the way of that progress?

Watch “Feeding the Blooms,” a Great Lakes Now segment that Ruck produced:

Great Lakes Now: It would have been easy to just show the “problem” of the algae blooms and blame it on agriculture. Tell us about your portrayal of farmers in the documentary and how that side of the issue is really more complex than people might realize.

Ruck: What I realized in making this film is that we should state the clear distinction between what we call “farms” and “farmers” versus “industrial agriculture”. The agricultural lobby uses phrases like “our farmers” to describe both and that’s really what is standing in the way of an honest conversation about the drivers to the problem.

“Farmers” are practical people with common sense and ingenuity, and they are really great at solving problems. The vast majority want to take care of the environment the way they want to care for their farm. Unfortunately, the way the system is set up benefits mostly the largest farms – farming on an industrial or near-industrial scale.

The condition of Lake Erie is a consequence of the way we have the Farm Bill set up. Small farms or farmers just getting started – farmers truly interested in soil health, crop diversity, and nutritional content, minority-owned, organic – there is very little in the budget to help these farmers out. Instead, the money goes to farming at scale, or industrial agriculture, which is fueling innumerable issues around the country.

Watch “Toxic Algae and the Climate Conundrum:”

Water scarcity, water pollution, fish die-offs, harmful algal blooms. So really what needs to happen is the use of language that distinguishes between industrial agriculture which is likely amplified or perpetuated by national policies and the family or small farm. The lobby wants you to think when we are questioning one we are questioning all of them. They want the non-farming public to see any criticism of the agricultural system to be seen as a criticism of all farming. And that’s a really powerful message in places like Columbus, Ohio or Washington, D.C.

Unfortunately, that’s the politics of it all. In truth, what needs to happen is for the food-growing system – the Farm Bill – to be completely overhauled in a manner that supports what we think of generally as “farmers” in order to foster a system that is both healthy and sustainable for working farmers and consumers and makes it more difficult to operate on an industrial scale where so many of the environmental problems we are facing begin.

Great Lakes Now: Since you started contributing to Great Lakes Now, in addition to algae bloom topics, you’ve work on stories about fossils in the Great Lakes region, the Water’s True Cost project, a lighthouse restoration and more. What drew you to these stories? Is there a common thread that audiences can connect them with?

Ruck: Some of these stories are projects that the team throws my way and asks me to dig into and they are just fun stories that people would be interested in. Others really dive into issues like our water infrastructure and the future of supplying Great Lakes citizens with clean water – something we take for granted. I think what I like to do is find a balance between stories where there’s a clear right vs wrong aspect to it, but that can get confused by wordsmiths and talking points and stories about fundamental research and what it can teach us about our understanding of the planet.

Great Lakes Now: Your segment “Lake Huron Sinkholes” is the most-viewed video on Great Lakes Now’s YouTube channel. What do you think makes that video and story so popular?

Ruck: For me, I this story is interesting because it’s about fundamental, basic research and exploration. Before we started looking at the bottom of the lakes in high definition with multibeam sonar, there was very little we knew about the bottomland of the Great Lakes. The fact that the Great Lakes has surprises like sinkholes and microenvironments like the low-oxygen, microbial ecosystems we find in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary is exciting. They’re like deep sea vents you might find deep in the ocean or the kinds of basic systems we might look for on other planets. Sinkholes in Lake Huron – and there are others around the lakes – are a glimpse into the early days of the planet and there is so much they can tell us still.

Great Lakes Now: Going back to “The Erie Situation,” what do you hope audiences take away from your piece?

Ruck: I want audiences to understand that ultimately food is grown in a manner that is supported by consumers. You vote for how you want something grown by what you purchase at the grocery store or at the farmer’s market. If you want your food to be fast, cheap, low-nutrient and low cost, expect more “Lake Erie’s” on the horizon.

If on the other hand the quality of your food is a priority, in terms of nutrition, diversity, humanely raised, locally grown, etc., and you want your lakes, rivers, and streams to also be healthy, people need to start voting with their dollars. We need to raise these issues to national importance, but it starts locally with what you buy, where you buy it, and how you want it made. The system will respond to what the consumer demands. But make no mistake: powerful interests want to keep the current system in place because a few people are making a lot of money keeping it that way.

Videographer David Ruck on assignment for Great Lakes Now in August 2020. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Outreach Media.

Great Lakes Now: What’s next for you? Can you talk about the next big project yet?

Ruck: I’m about to go to Nepal for a month to kinda reset and digest everything that I’ve learned creating “The Erie Situation” with my incredible team. I have lots of ideas and interests which could constitute what might be the next project, but I don’t want to dive into anything on that level just yet.

I think it’s a safe bet my next project will also involve exploring human impacts on ecosystems, but which direction I go with that is TBD. In the meantime, I’m exploring shorter projects that illustrate Great Lakes issues including science, research, habitat restoration, environmental monitoring, exploration, and how people interact on a spiritual level with the Great Lakes. I think it’s important to take time between large projects and I like to cast a wide net on a diversity of possible next adventures before settling into just one.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

“The Erie Situation” – and beyond

Featured image: Videographer David J. Ruck on assignment for Great Lakes Now in August 2020. Photo courtesy of Great Lakes Outreach Media.