I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

One of the most mesmerizing sights to behold underwater is the fluid undulations of a synchronized school of fish.

Not all fish swim in schools. Many swim together in loosely formed groups but they do not move together as a single unit. Predators like bass, perch, trout and walleye often swim in these small loose groups which are called shoals not schools.

A true school of fish is a single entity that can be made up of hundreds or even thousands of individuals that magically, mystically moves as one. While beautiful to watch, schooling is actually a defensive mechanism.

Forming large shifting shapes makes it difficult for predators to single out individuals.

When threatened, some schools tighten into perfect spheres called bait balls. Other schoolers like shiners and shad perform elaborate, perfectly synchronized maneuvers to avoid being eaten. When a predator strikes their school, they split off in opposite directions and then reform almost instantaneously.

- I Speak for the Fish: Taking the measure of a rainbow darter

- I Speak for the Fish: Not all lampreys are killers, but all are paying the price for their reputation

- I Speak for the Fish: Inside a trout feeding frenzy

Fish on the perimeter of any school are the most vulnerable while those near the center are protected, giving rise to the olde adage that there is safety in numbers.

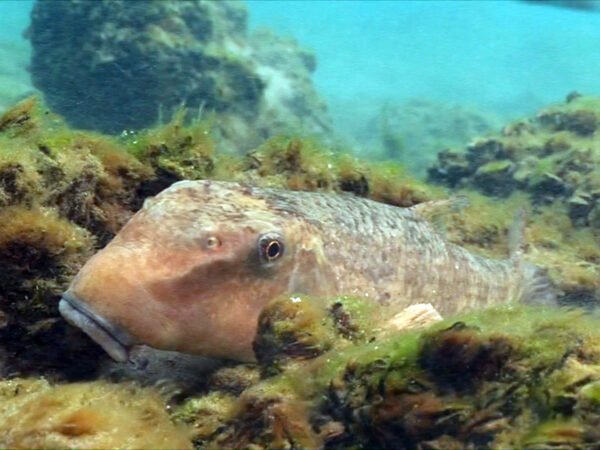

Gizzard shad are a type of herring. They grow to an average of about 19 inches.

Shads’ sterling color offers another line of defense against predators as the school can shimmer into one massive silver form. Their metallic bodies also display a distracting flash of light when they catch the sunlight just right.

Recent studies have found that schooling is not a learned behavior but rather part of a fish’s genetic code. There is no learning curve. Shad hatch with the ability to school.

Blackouts

In her novel, The Everglades: River of Grass, Marjory Stoneman Douglas recounts an early visit to the Everglades. Douglas vividly described her wonder at seeing flocks of birds so dense they blocked out the sun in America’s sunshine state.

Witnessing that level of abundant biodiversity is increasingly rare these days. So far, my husband, Greg Lashbrook and I have only experienced it once in the Great Lakes.

Shad blackout. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

A fisherman told us the shad were running in the St. Clair River.

We picked a familiar spot in the upper river where the sandy bottom extends as far as the visibility allows. On this day, the river blessed us with 40 feet of visibility.

One of the biggest challenges of filming schooling fish is that they seriously dislike our exhalation bubbles. Much like the ducks I recounted in a previous column, schooling fish do not like divers breathing below them.

Thankfully, the shad were a bit more tolerant than the mallards.

We settled ourselves and our camera on the downstream side of a steep slope beneath a large mound of sand. The sand ridge sheltered us from the river’s strong flow and shielded us from view upstream.

While we waited for the school of shad to move closer, I found myself admiring the rippling sand surrounding us. The crystal-clear water allowed the sun to penetrate all the way to the white-sand bottom where it cast the same wavy shadows as in an arid desert.

The school approached slowly. The outliers became a little erratic when they spotted us but when we remained still and non-threatening, the school coalesced above us. It was noticeably darker in the shade of the shad.

Shadows no longer rippled across the sand as thousands of silver bodies began to deflect the sunlight from reaching the bottom. But we were not yet beneath the bulk of the school. As more of the school shifted over us, it got even darker.

Looking up, I could barely distinguish individual bodies. It just looked like one massive shimmering grey mass that moved with the grace and ease of a dolphin. And then it got really dark.

The school of shad was so dense that when the center passed overhead it blocked every spec of sunlight from reaching us.

Our eyes and lungs bulged as we watched the school glide over us in perfect synchronized formation. Within too-few seconds, sunlight began to once again dart between the bodies. And within just a few minutes the entire school had moved past us.

Moments like these help me to imagine the Great Lakes in all their historical abundance.

A school of shad. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Glory Days

I recently came across an excellent NPR article with some super interesting historical information about shad.

- Shad have been an important food source for some Native American communities since time immemorial.

- George Washington made a good income after his presidency by selling shad that were netted from the Potomac River at his Mount Vernon estate. In 1772, he reportedly caught and sold upwards of 1 million shad.

- Civil War soldiers were given shad in their rations.

- The fishery began to decline in the late 1800s due to the now archetypal insults of overfishing and habitat loss.

One of the classic tomes of Great Lakes research is The Fishes of Ohio by Milton Trautman. In a 1992 memoriam, Harold Mayfield called Trautman’s book “an indispensable reference for anyone studying the freshwater fishes of North America.”

From a young age, Trautman was a keen observer of Lake Erie and when referencing shad, he notes that “spectacular permanent decreases in abundance have taken place.” Trautman attributed their decline, in part, to the loss of nearshore vegetation beds used by shad for feeding and reproduction.

Juvenile shad eat zooplankton but adults are herbivores. Gizzard shad are one of the few species in the Great Lakes that can exist solely on plant material because of their specialized digestive systems which are able to breakdown aquatic plants, according to the ROM field guide.

In The Fishes of Ohio, Trautman provides some helpful observations about the state of gizzard shad before 1950.

In the spring when the surface of Lake Erie was smooth, a great area estimated at 10 or more acres thrived with dozens of juveniles per square meter. These giant schools could be observed swimming just below the surface.

Trautman found “Concentrations of gulls, ducks, and other species of waterfowl remained for days feeding avidly upon this readily available food supply. Since 1950, only infrequently have birds been observed eating young shad.”

He speculated that the increase of recreational boat traffic may have been another contributing factor in the fishery’s decline due to “boats traveling at high speeds leading to the mortality of fry from propellers.”

Jarring Shad

We were heading back to shore after the school passed that day when Greg noticed the jar. The clear glass vessel was laying on the river bottom. It appeared to be a discarded 24-oz. pickle jar although the labels were long gone. It was large enough to hold about 16 pickle spears.

Right then, it contained three small gizzard shad.

The three young fish had managed to swim straight into the jar. Now, they were too tightly packed to back out. Their tails were wiggling, so they were alive, but likely not for long.

Greg picked up the jar and pinched the edge of a protruding tail. With a gentle tug he pulled the first fish free. It seemed a little disorientated but quickly recovered.

I watched it zoom away while Greg worked on freeing the next fish.

Shad in a jar. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

He repeated the tail pull with the second shad but it came out and rolled onto its side when released. Greg righted it and performed fish CPR by gently rocking it to help aerate its gills.

It didn’t zoom away but it did revive and swam off into the blue.

Greg turned his attention back to the jar. The last fish was the smallest and its tail did not extend outside the jar’s lip. Try as he might, Greg could not reach inside far enough to grasp its tail.

Nothing was holding the fish inside the jar so Greg tried shaking it. He shook the jar like he was trying to get the last bit of ketchup out of the bottle, to no avail.

When Greg started moving towards shore, I figured he was going to take it topside with us. To my utter astonishment he stopped beside a small rock and with one quick whack smashed the jar to pieces.

The shad was lethargic which seemed understandable given its jarring ordeal and explosive release. Thankfully, it did not require resuscitation before leaving us to rejoin the school.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Modern sea lamprey control pits technology against the invaders

Who caught the world’s largest muskie? Even the experts don’t agree

Featured image: Gizzard shad are a type of herring. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)