Overall water usage in the Great Lakes is dropping, largely due to water conservation and management efforts, according to the Great Lakes Commission’s most recent water use report.

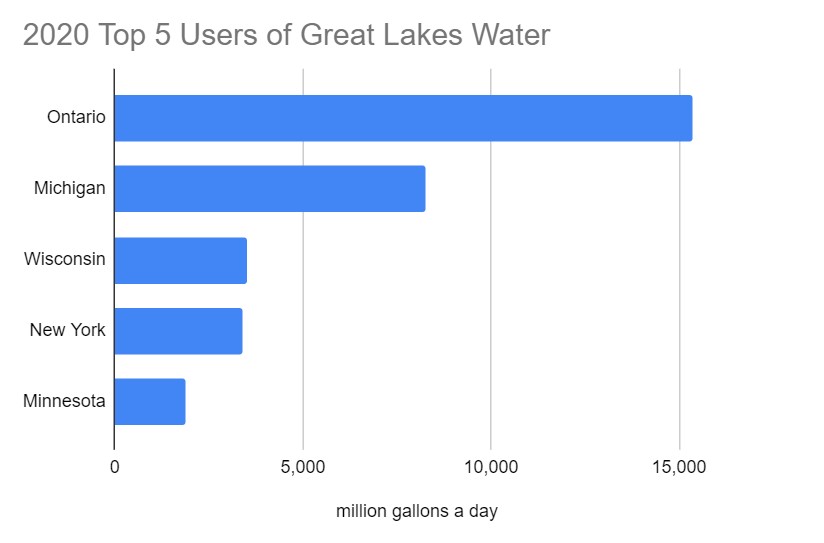

The GLC compiles annual water use data, a stipulation outlined in the 2008 regional water use agreement known as the Great Lakes Compact. In its most recent water use report, the GLC outlines the following jurisdictions as the top five users of Great Lakes water: Ontario, Michigan, Wisconsin, New York and then Minnesota.

(Image by Natasha Blakely, data source: Great Lakes Commission)

But just because these territories use large amounts of water doesn’t mean they are consuming the most.

According to the GLC, water use is when water is removed from its source for any purpose whether or not it returns, while water consumption is the portion of water use that is not returned and is lost to evaporation, incorporation into products or other processes.

Many water users struggle to understand consumptive use or estimate it properly, said Andrew LeBaron, Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy environmental quality analyst.

“There’s a key distinction between water use and water consumption,” LeBaron said in an email. “Both are required to be reported by all large quantity water users in Michigan.”

Ontario is the largest user, but not consumer, and an overwhelming majority of its water use is regenerative through energy creation processes.

From 2016 to 2020, Michigan, Ontario, Indiana, New York and Quebec were the top five consumers of Great Lakes water.

In 2020, the Great Lakes Basin lost a total of 377 mgd (based on consumption and water diversions). This is a noticeable change from the 444 mgd the Basin gained during 2019. Tom Crane, GLC Deputy Director, said this change was caused by a drop in water returned from the Long Lac and Ogoki diversions, which divert water from the Hudson Bay watershed into northern Lake Superior.

Crane said this deviation was not a cause for concern and is to be expected when managing a complex water system.

“As a region, we do not have a water supply shortage because we have so much fresh surface water, but there can be localized areas within the states and provinces, they have water shortages, and those can be due to a variety of things related to population growth, industries, groundwater, or depletion of groundwater resources,” Crane said.

Largest consumers: industry, public water

In the Great Lakes Basin, public water supplies and industrial water consumption are continually both the largest users and consumers of water. In 2020, public water supplies accounted for 5,165 mgd withdrawn from the Basin, with 575 mgd consumed daily. The industrial sector accounted for 4,043 mgd in withdrawals and 532 mgd consumed daily.

GLC data does show that processes such as water turbine-generated electricity and hydroelectric power, such as dams, withdraw thousands of millions of gallons a day, but the processes are not noted as large consumers as the water is returned to Basin through the energy creation process.

The state of Michigan is the largest consumer of Great Lakes water, according to recent reporting by the GLC. According to data provided by LeBaron, Michigan’s estimated top five water consumers are two users in the industrial sector, two users in the energy creation sector and one public water provider. The data did not name names, and the GLC declined to provide them.

Because of the fickle nature of monitoring water consumption, LaBaron cautioned that the data provided aren’t always accurate.

Across the Great Lakes region, industrial facilities make up a large percentage of water users and consumers. In Illinois, the city of Joilet—which wants to start using Lake Michigan water by 2030 as its aquifer is drying up—is home to a large warehouse and industrial sector reliant on millions of gallons of water. GLC’s water use reporting shows that Lake Michigan is continually the largest supplier of water to industrial consumers compared to the other lakes.

While other jurisdictions waver between various sectors for their main uses of Great Lakes Water, the water the state of Indiana uses is almost entirely for the industrial sector.

“Abundant freshwater from Lake Michigan has promoted the development of an extensive urban and industrial belt along Indiana’s coastline,” stated the GLC’s 2020 Water Use Data Report.

A bird’s eye view of Port of Indiana-Burns Harbor. This bustling port is one of the busiest shipping hubs in the Great Lakes. (Photo Credit: Ports of Indiana – Burns Harbor)

From 2019 to 2020, Indiana saw a 14% increase in its consumption of Lake Michigan water. This increase is attributed to “increased use at a steel plant” by the GLC.

Crane said that while small pockets of the water system can experience water shortages, overall usage of Great Lakes waters has gone down in recent years, citing an increase in water conservation processes in the region’s communities, and a change in the industry use.

“Some of the older industries and some of the high-water-using industries have either moved out of the region or have become more efficient in the way that they use water,” Crane said.

While overall use of the Great Lakes waters has declined in recent years, Crane said he is keeping an eye on agricultural uses for water, such as irrigation and livestock uses. While those two sectors make up small percentages of overall use, he said climate change is impacting how these sectors respond to and predict their water use, which can cause spikes in usage.

“When we have more intense rainfall events that are occurring at different times of the year,” Crane said. “We also have long stretches in any given growing season that are hotter and drier.”

Keeping Great Lakes water in the Great Lakes

All of the data collected by states that use Great Lakes water is a part of a stipulation spelled out in the Great Lakes Compact.

The compact, signed in 2008 by then-President George W. Bush after years of regional water battles, prohibits the creation of new or increased water diversions to communities outside of the Basin.

Water has become an increasingly finite resource around the world and country. The U.S. Forest Service warns half of the current basin won’t be able to keep up with current monthly user demands by 2071.

Crane said, among other things, outside communities looking at Great Lakes water led to the eventual creation of the compact.

“Most of those proposals never went anywhere,” Crane said. “Most of them were not feasible either for engineering or for economic reasons. But nonetheless, there was an awareness that people were interested in the water.”

In 1988, Sault Sainte Marie businessman John Febbraro sought to bottle and sell up to 427,000 gallons of Lake Michigan water a day to Asian countries. The plans were eventually thwarted, but fear of increased sale of Great Lakes water lingered.

“If one Asian shipper and one Canadian water retailer believe it is economically feasible to ship Great Lakes water to Asia, the door is open to putting the waters of all the Great Lakes on the market,” then-US Rep. Bart Stupak (D) of Michigan told The Chrisitian Science Monitor.

The compact prohibits the sale of water, but in recent years, Great Lakes water diversions have increased. These diversions are few and far between while being highly contentious amongst environmental groups and local water users. Nestle’s attempt to increase its withdrawals for its North American bottled water business drew widespread public protest. Eventually, the company that bought the bottled water business from Nestle dropped the permit.

Back in 2015, when the Southwest was reeling from a different drought, the idea of a Midwest-to-Southwest pipeline for Great Lakes water was floated, but the compact warded this idea off.

Crane said there are a variety of hurdles for outside communities to receive Great Lakes water, including logistics, costs, legality, and political will. He said there are currently no active proposals for outside communities seeking these waters, but that could change.

“As the water crisis continues in some of these different parts of the country these proposals are likely going to start coming up again,” Crane said.

In addition to non-Great Lakes communities looking at the water, Crane said it is likely for “straddling” communities to propose more water diversions to consume Great Lakes’ water.

In 2016, the Wisconsin city of Waukesha secured a permit to use roughly 8 million gallons of Lake Michigan water per day as the municipality needed to replace polluted water.

Soon after, controversial Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer Foxconn wanted to use upwards of 7 million gallons a day for a Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin, LCD screen factory. Unlike Waukesha’s request, Foxconn only needed (and eventually received) approval from the state of Wisconsin for its water diversion. The state of Wisconsin has been embroiled in controversy over land and water use by the tech company since 2017, but none of the promised screens have been produced with Great Lakes water.

More recently, cities around the Great Lakes have seen their underground aquifers or water infrastructure dry up or falter, causing them to look elsewhere for a public water supply. In Joilet, Illinois, a city roughly 45 minutes southwest of Chicago, anticipates its aquifer will be unusable as early as 2030, prompting area officials to begin looking at Lake Michigan water. On the outskirts of Green Bay, the rural village of Denmark has recently announced its groundwater wells are not repairable and the community will soon join the Central Brown County Water Authority to receive its water supply from Lake Michigan.

Crane said the GLC will continue to monitor incoming proposals to divert water, but he also expects more communities that rely on groundwater will begin to shift to Great Lakes’ water due to anything from increased demand from growing populations seeking climate refuge to cities abandoning groundwater due to PFAS pollution.

“In the next 10, 15, 20, 25 years, if we begin to see people coming back into the region, communities are going to have to be able to accommodate the increase in population which will put pressure on the water,” Crane said.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Lake Michigan Water Pipeline: Waukesha receives federal loan for water supply project

Question of Diversion: Great Lakes governors group silent on future water threats

Company formerly known as Nestle drops water withdrawal permit

Featured image: Lake Superior from Presque Isle Park in Marquette, Mich. (Photo Credit: Zosette Guir/Detroit Public Television)