I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

How many species of lamprey live in the Great Lakes?

If you answered five without asking Google or phoning a friend, you did better than me. I thought it was three.

At this point, I expect most people to have heard of sea lamprey, the notorious headline stealing invasive species. But there are four native species of lamprey in the Great Lakes that generally get reviled by association even though none kill their host fish: silver, chestnut, American brook and northern brook.

All lamprey species in the Great Lakes reproduce in the same way. Male lampreys prepare a nest site by moving rocks to form a 2-foot circular depression with a ring of rocks around the edge.

Males secrete a reproductive pheromone that drifts downstream and out into the lakes. It’s a powerful attractant for other lamprey who follow the scent to the nest site.

Females enter the nest site and attach themselves to a rock. The male then attaches himself to the female’s head, coils his body around her, and they spawn.

After hatching, the larval lamprey burrow into the river bottom where they can remain dormant for up to 12 years before morphing into adults. While buried in the river bottom the larvae will eat plankton and microscopic bugs.

As adults, some lampreys are parasitic – meaning they attach themselves to a host fish – while others are not.

The American brook lamprey which is the most common lamprey species in the Great Lakes have such a short life span as adults that they don’t bother to eat anything!

They just hatch, make or find a nest site, spawn and die.

A Canadian study found the silver and northern brook are genetically indistinguishable, according to the Royal Ontario Museum Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario, so they may actually be the same species that evolved with different adult feeding techniques. Silver lampreys are parasitic while northern brooks are not.

It’s common to see lake sturgeon with one or more native silver lampreys attached. In contrast, my husband has filmed hundreds of adult lake sturgeon, and we only have footage of two individual adults with a sea lamprey attached.

Many adult sturgeon carry obvious marks from prior sea lamprey attachments. The large circular scars are unmistakable. But given that sturgeon can live for more than 100 years, some of those scars could be 80 or more years old.

As a champion of native species, it naturally irks me to see article after article extolling the horrors of sea lampreys without even mentioning that there are four other native species. This tends to fuel a “kill them all” mentality that many well-intentioned individuals adopt.

In addition to not killing fish, native lampreys are actually beneficial. The ammocoetes are like little farmers tilling the river bottom which distributes nutrients and helps to keep the river healthy.

Surprisingly to me, sea lampreys are actually native to Lake Ontario. It was manmade canals that granted them access to the upper lakes in the 1920s. For perspective, when they reached Lake Superior in 1938, World War II had yet to be fought, Ella Fitzgerald was on the top of the music charts and ballpoint pens were a new invention.

I think it’s safe to say, they have been here for a very long time.

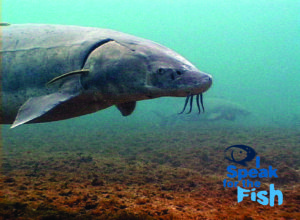

A sturgeon swims by with a silver lamprey attached to it. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook / PolkaDot Perch)

Yet even 100 years after their arrival, sea lampreys continue to garner headlines as if they are a current threat in the Great Lakes. I’m guessing every politician and celebrity in the world could only dream of such media staying power.

I just wish stories that sensationalize sea lampreys as killing thousands of fish in the Great Lakes each year would clarify that as historical rather than current information.

For more historical context, sea lampreys have been well managed in the Great Lakes since Neil Armstrong walked on the moon.

There is no question that the sea lamprey invasion of the upper Great Lakes was devastating for the ecosystem as a whole. I’m not suggesting otherwise. Thankfully, that was not and is not the end of the story.

In the 1940s, barriers were installed in rivers to try and prevent the sea lamprey from traveling upstream to spawn. But they are hard to maintain and are not always effective during spring flood events. Some physical barriers can also limit access for other species.

Stopping the sea lamprey invasion required a more aggressive approach.

The Great Lakes Fishery Commission was created and funded in the 1950s specifically to manage the sea lamprey invasion. With their support and funding, a new pesticide – 3-trifluoromethyl-4-nitrophenol – was created.

In 1958, the first successful field test of the newly developed lampricide was welcome news across the basin and a turning point in the sea lamprey invasion. An upcoming segment on Great Lakes Now will describe how lampricide is applied.

But just because a pesticide is effective does not necessarily mean that every stakeholder supports its application.

One of the concerns was that lake sturgeon and sea lamprey use the exact same spawning habitat. And the two species spawn at the same time of year. So, while lampricide has not been proven to harm lake sturgeon, there are some that question the wisdom of dumping a ton of pesticides into rivers where larval lake sturgeon are actively hatching.

Concerns over the use of lampricide contributed in part to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission’s funding of additional research into alternative control methods.

One of the alternative methods developed turns the sea lampreys’ mating ritual against them.

About 10 years ago, my husband and I visited one of our favorite Lake Michigan tributaries. The Little Manistee is a shallow river that gracefully meanders through the Manistee National Forest.

Standing on the riverbank, we could see a 3-foot metal cube sitting on the river bottom. The sides appeared to be constructed from steel chain-link fence. We had never seen anything like it before and immediately donned our gear for a closer look.

Underwater we were surprised to find half a dozen adult sea lamprey trapped inside the steel box. Our curiosity was officially piqued.

My post-dive inquiries found that the box was part of a research study.

Researchers have been able to copy the lamprey’s spawning pheromone. And it is such a powerful attractant that releasing a small amount from inside a steel cage will cause the spawning adults to willingly swim inside.

It’s a clever and very effective trap.

As part of my research for this column, I was curious to learn what the results of this study found and if the idea was functionally scalable.

As we observed, the pheromone traps work. But like all control methods they have limitations. They are more suited to small shallow tributaries than large deep rivers like the St. Marys. But they are great at capturing live adults for research purposes.

Some of the newly designed physical barriers are also effective in limiting the sea lampreys’ access to rivers while allowing for safe fish passage. Again, these barriers work better in some areas than others.

Lampricide remains the primary means by which sea lamprey are controlled in the Great Lakes.

So, a hundred years after arrival, where do we stand?

The real headline making news is that 90% of all sea lampreys have been eradicated from the Great Lakes!

The researchers I spoke with are all in agreement that complete eradication is unlikely. But then again, 75 years ago removing 90% from the Great Lakes was also unimaginable. Yet here we are.

Lampricides will continue to be a necessary tool in the management of invasive sea lamprey, but what about our four small native lampreys? How have they weathered the sea lamprey controls?

A recent article in the Journal of Great Lakes Research found that native lamprey species are “no longer found in about three-quarters of the number of streams in which they were historically present.”

My hope is that the decision to save lake trout and other native fish at the expense of native lamprey is the right choice. But there is still so much we don’t know about what the impact on our native lamprey will mean in the long run, so I guess only time will tell.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Inside a trout feeding frenzy

I Speak for the Fish: How the round goby changed the Great Lakes, twice

Featured image: A mix of native and sea lamprey (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook / PolkaDot Perch)

1 Comment

-

Sounds like native Lampreys just might be a “Keystone Species” to the upstream river environments akin to how the earthworm is a Keystone Species for soil