By Eleanore Catolico, Energy News Network

This story was first published on the Energy News Network and was republished here with permission.

This article is co-published by the Energy News Network and Planet Detroit with support from the Race and Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University.

It was the violent smells, his pounding headaches, and burning eyes.

Longtime resident and activist Robert Shobe’s home on Beniteau Street stands in the shadow of the Stellantis Mack Assembly Plant on Detroit’s east side.

Part of a larger complex, the plant occupies a large swath of industrial land, where thousands of hulkish vehicles like the Jeep Grand Cherokee are manufactured annually.

Shobe believes the car factory’s noxious fumes are assaulting his senses and health. His neighbors are hurting too.

“We’re still getting sick and having issues with outside air,” he said. “We need new policies and procedures in place to protect the citizens.”

For decades, environmental justice activists have been fighting polluting industries, which they say inflict long-term damage on their community’s health, well-being and quality of life.

Multiple state and federal mapping efforts are underway, aiming to better quantify the lived realities communities face because of their exposure to pollution and other environmental hazards. Among them are the Michigan Environmental Justice Screening Tool, or MiEJScreen, and the federal Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool.

These agencies hope such data-driven technologies will bolster their quests for environmental justice — which ensures all people are treated fairly and equally protected from environmental hazards through laws and regulations — following decades of citizen activism. But some environmental justice experts and activists remain skeptical that more data will create urgency to solve problems that have been common knowledge for generations.

They question whether they’ll make any meaningful difference in their lives because of regulators’ past decision-making. Environmental justice activists have long scrutinized the ways regulators have continued to grant permits allowing companies to operate where they’ve lived, underscoring a legacy of distrust. Some have described these efforts as an empty measure with no regulatory teeth.

While urgency around the climate crisis intensifies, people who live in communities heavily impacted by pollution are frustrated with agencies for failing to limit industry on their behalf in the first place.

“This situation has been going on [for a while],” said Shobe, referring to the community’s issues with Stellantis. “It’s overwhelming.”

Visualizing environmental hazards

While still in its draft stage, the MiEJScreen represents another crucial step for Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s broader environmental justice mandate.

Three years ago, Whitmer issued an executive order which created the Office of the Environmental Justice Public Advocate, tasked with advancing Michigan’s environmental justice initiatives and investigating related concerns and complaints. In 2020, Whitmer formed the Michigan Advisory Council on Environmental Justice, which advises the state on environmental justice actions.

The tool is intended to help guide policy decisions and increase public engagement and participation in the permitting process and enforcement matters, as well as where resources should go.

“MiEJScreen was developed to better identify communities and locales disproportionately impacted by environmental hazards and to provide a common platform for assessing what communities face,” said Jill Greenberg, a spokesperson for Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, which is helping oversee the development of the tool.

“The goal of the tool is to have a common set of data as we identify the ways we can better work toward ensuring everyone in our state benefits equitably from our environmental laws and regulations.”

The creation of Michigan’s mapping tool follows similar endeavors to visualize environmental conditions and risks.

The MiEJScreen was developed by several state departments working together and modeled after California’s CalEnviroScreen and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s EJScreen. Maryland and New Jersey have launched similar tools, and Wisconsin is developing their own.

Michigan’s mapping tool shows how people living within a census tract may experience potential environmental threats. The tool also shows socioeconomic characteristics like racial composition and income level, and health data, such as rates of asthma or heart disease.

The tool also allows users to dig even deeper: They can learn whether or not a community was once a victim of the racist housing practice called redlining or is classified as a food desert — an area where people have low access to affordable, nutritious food.

In all, there are 26 environmental, socioeconomic, and demographic indicators, according to the tool’s factsheet. An overall score, displayed as a percentile, is calculated by multiplying an environmental conditions subscore and population characteristics subscore together.

A collective burden

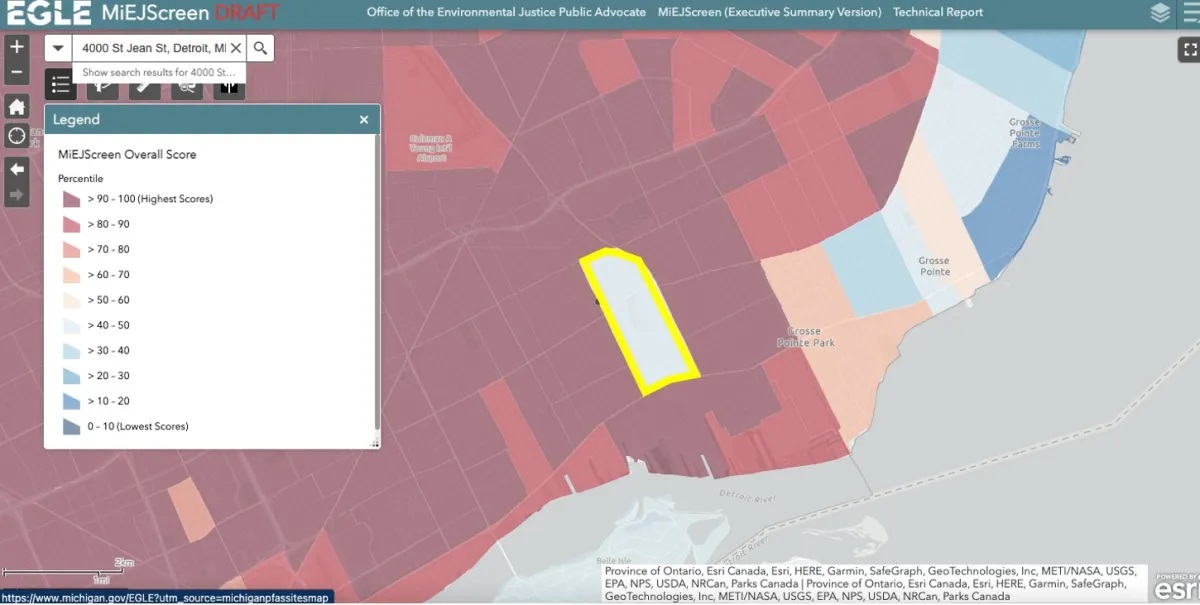

Shobe is among the nearly 17,500 people who live across the nine census tracts bordering the Stellantis plants along Conner, Jefferson and St. Jean Streets. One of the tracts near the Stellantis complex in Detroit is shaded red on the MiEJScreen map, with an overall score of 99 out of 100.

The people living in Shobe’s neighborhood are mostly Black and many live in poverty. They confront greater risk and exposure to pollution and other detrimental environmental effects.

A screen capture from the MiEJScreen tool shows the area around the Stellantis complex, highlighted yellow. The dark red surrounding the complex represents the highest score for environmental injustice on the tool’s scale. (Photo Credit: Energy News Network)

Since the Mack plant became operational last year, the state Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) has received multiple community complaints.

Stellantis has already incurred three odor violations and another violation for failing to properly install emissions control ductwork, which ended up leaking volatile organic compounds. These harmful chemicals, when contaminating the air, can irritate the eyes, nose, and throat.

Environmental regulators said the Stellantis complex doesn’t pose immediate health threats. That conclusion doesn’t ring true for Shobe.

Shobe is among five residents who filed a federal civil rights complaint against EGLE for issuing permits that allow Stellantis to increase emissions of air pollutants, despite the area’s high asthma rates.

Nick Leonard is the executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, the firm that filed the complaint on the residents’ behalf last November. Leonard said communities of color often face a disproportionate level of environmental risks.

“Part of the reason that’s come to be is because, essentially, race and disparate impact hasn’t been given enough consideration by the state in its decision making,” Leonard said.

Scientific research shows race is the strongest predictor of where toxic facilities operate. Meaningfully evaluating race can help regulators make more informed assessments on whether decisions meet environmental as well as civil rights standards.

Leonard hopes the tool will be used to inform policy-making decisions, like the approval of air quality or hazardous waste permits.

Greenberg said the MiEJScreen will not change laws and regulations, but will help inform processes like community engagement and translation.

“While we have to work within existing environmental laws and regulations, the tool certainly will help shape and impact the permitting process,” she said. “EGLE is also encouraging the regulated community to use the tool early on in their process prior to submitting permit applications.”

So far, EGLE has yet to release specific plans on how this tool will be implemented in its permitting processes moving forward.

In Flint, environmental justice activists are clamoring for regulators to understand the full scope of the coalescing toxic threats communities face year after year.

Thick plumes of smoke billow from the nearby Genesee Power Station incinerator. Automotive suppliers and meatpacking plants dumped so much industrial waste into the Flint River that its untreated waters, along with government negligence, spurred the city’s lead crisis beginning in 2014, one of biggest public health disasters in a century.

So when an asphalt company chose to construct its plant on a sprawling industrial park across the street from River Park Townhouses, a large public housing complex where many Black and low-income residents live, Mona Munroe-Younis and dozens of others fought to halt the permit which would allow the company to build its plant.

“We’re not saying, ‘Don’t build a plant.’ We’re saying, “Don’t build it in this location.’ It’s really egregious to do that,” said Munroe-Younis, who also serves as the executive director of the Environmental Transformation Movement of Flint.

“We are hearing a lot of reports of high levels of cancer and asthma and other upper respiratory problems,” she said. The public housing complex is located in another area of potential risk, receiving an overall MiEJScreen score of 77.

Munroe-Younis has measured optimism for the promise such environmental justice screening tools may help fulfill, like identifying neighborhood-specific hotspots.

While their bid to stop the construction of the asphalt plant was unsuccessful, the Flint environmental justice group, along with other local organizations, filed a federal civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development last December, alleging the approval is part of a broader pattern of discrimination. They also sued EGLE over granting the company’s air permit.

“Specific to the Ajax permit, EGLE recognizes this area’s history, challenges and the disproportionate environmental health burdens that already exist in this community,” Greenberg said. “While the law does not allow EGLE to make a permit determination based on the EJ status of a community, the agency can help ensure through permit conditions that a new facility — if permitted — has minimal impact on the neighborhood.”

That’s not a satisfying answer for Munroe-Younis. It’s why she wants officials to use the MiEJScreen to conduct deeper risk assessments.

“It’s really important to have tools like this to be able to do a good cumulative impact analysis during the state’s permitting process,” she said.

A cumulative impact analysis considers how the total burden of environmental stressors and the ways they interact, affect health, well-being and quality of life for an affected population over time. She said the current permitting process may underestimate a community’s true level of risk.

“It’s really a very incomplete picture for making a permanent decision,” she said.

A legacy of need

As communities across the country grapple with toxic air and sewage-filled waterways, environmental justice activists want more financial relief to help make their neighborhoods more resilient against these hazards.

Some help may be on the way. The Biden administration is developing the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, which is designed to guide federal agencies to offer more direct aid.

Still in its beta form, the federal climate tool supports the implementation of a broader environmental justice strategy called the Justice40 Initiative, whose primary goal is to send 40% of overall climate benefits, such as federal loans or grants, to communities deemed disadvantaged.

Such benefits could also include funding for weatherization projects, which help fortify homes and buildings against the elements while also reducing energy costs and retrofits, or improvements to commercial buildings in order to decrease energy waste.

The map is populated by a mix of federal data, including census estimates. In the wake of the 2020 census, some cities, including Detroit, have challenged the results, claiming the U.S. Census Bureau significantly undercounted residents.

Significant holes in the data could fail to represent a community’s true level of risk, vulnerability, and need, said Justin Schott, a project manager for the Energy Equity Project, a national mapping effort to determine whether or not communities have equitable access to clean energy services and programs. (Editor’s note: Schott is a member of Planet Detroit’s advisory board).

Because of these gaps, Schott worries climate benefits may not flow toward struggling communities.

“That’s something that I find really concerning,” he said. “How are we dealing with these communities when there’s a blank?”

In the tool, disadvantage is measured across a range of categories, from diesel emissions exposure to high energy bills.

A community may be defined as disadvantaged if it scores above the threshold for environmental or climate as well as socioeconomic indicators. For this tool, many of the threshold minimums are set at the 90th percentile.

Setting a high bar for disadvantage, Schott said, could also mean some communities may not receive benefits if they fall below the threshold.

There’s also one glaring omission from the federal climate tool many environmental justice experts and advocates agree is a true metric of disadvantage: race.

After the White House rolled out the tool in February, many environmental justice advocates volleyed criticism against the exclusion of race. In response, government officials said including race could imperil the tool by attracting legal challenges.

In an email, a spokesperson from the White House’s Council on Environmental Quality acknowledged how race contributed to where pollution has been concentrated and led to a lack of government investment, enforcement, and help.

“The environmental and socioeconomic data we are using in the tool endeavor to reflect this reality and legacy of injustice,” the spokesperson said. “We launched the tool in beta version so that we could solicit feedback from the public and update the tool to identify more accurately communities that are shouldering a disproportionate share of environmental burdens and climate risks.” The spokesperson did not address questions about the tool’s disadvantage thresholds.

If race isn’t included, then the federal climate tool’s information will be flawed, said Detroit activist Theresa Landrum.

“We know historically race, throughout America, has played a major factor on how Black people and low-income people are treated, where they live, where they’re forced to live in, and environmental justice issues that they face,” she said. Landrum, along with Leonard and Munroe-Younis, served on Whitmer’s environmental justice council.

The arc of Michigan’s toxic legacy is long, stemming from generations of environmental racism, which saw laws and policies fail to protect BIPOC communities from pollution and health threats.

Landrum is a longtime resident of 48217, located on the city’s southwest side. The area lies in the epicenter of heavy industry and truck traffic and once held a reputation as the most toxic zip code in Michigan. Many Black and low-income residents live here.

These days, different studies and limited air monitoring describe competing realities of the magnitude of contaminated air burdening these neighborhoods. But this area’s reputation for pollution is undisputed, keeping the more apocalyptic moniker of “sacrifice zone.”

Landrum is angry that impacted communities, like her own, won’t get federal dollars to create equity and resilience in their neighborhoods if race isn’t considered.

“The ones who’ve gotten the least over the years, who’ve suffered the most, must be prioritized,” she said.

Shobe, the Detroit resident, remains skeptical. Based on EGLE’s permitting track record, he doubts such tools will meaningfully influence policy actions that will help protect his neighborhood.

“I think any tool that lets us know something about our environment is useful,” he said. “But as far as protecting certain communities and impacted areas, I don’t see it having any real value. … This doesn’t make a difference.”

The public comment period for the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool has been extended to May 25. To leave a comment, go here.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Mapping tools help Ohio cities chart course for environmental justice

“Thank God that smell is gone”: Detroit incinerator to be demolished after decades of complaints

Featured image: I-75 near the Marathon Oil Refinery complex in 48217. (Photo courtesy of Bill Kubota)