I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

Some dives are so pivotal that they permanently fuse themselves into my memory bank.

I’ll never forget my first open water dive in the St. Clair River under my family’s dock, or the first time I looked for a drowning victim as a member of the St. Clair County Sherriff Department Dive Rescue and Recovery team. I can clearly recall the moment and know the exact spot on my right calf where a male sturgeon struck me during a spawning run. And I’ll never forget the night dive where I had my first and, so far, only American eel sighting.

And then there was the dive when the Great Lakes changed forever.

Greg and I were diving behind my parent’s house just as we had dozens of times before.

I was still a newbie at the time, so after each dive Greg would tell me the names of all the fish we saw. I remember asking him what fish had the big black dot on its dorsal fin and was shocked when he said he didn’t know. He had never seen one before.

Back home, we looked through all our Great Lakes’ fish identification books but didn’t find anything that matched what we saw. Curiosity had us calling one of our favorite fish experts.

We met and become friends with Gary Longton, a research biologist working at the Detroit Edison Belle River power generating station, when we were working there as commercial divers.

We called and asked Gary which fish was about 6 inches long with a round head, a light grey body and a big black dot on its dorsal fin. We noted the concern in his voice as he pressed us for details. Where exactly had we seen it? Our answer, on the river bottom in 10 feet of water, a mile upstream of the plant, was not what he wanted to hear.

But without the actual fish, a photo or even some shaky video, it was impossible to know for sure what we saw.

Just a few weeks later, David Jude, a research scientist at the University of Michigan School of Environment and Sustainability, was doing a study at the Belle River Power Plant.

His research team was monitoring impingement, which is a fancy way of referring to all the fish caught and killed by the power plant’s water-intake filtering system. For days, the researchers laboriously sorted through hundreds of dead fish carcasses to identify all the impacted species.

“I picked this one up and I thought, ‘I haven’t seen anything like this before,’” Jude said, while reminiscing about the discovery. His initial thought was that it was “a darter of some kind.” Except darters don’t have fused pelvic fins and this fish did.

Jude took the fish to his colleague Jerry Smith at the University of Michigan Fish Museum. Smith quickly identified it as a tubenose goby. Although it was an invasive, an intensive literature review satisfied the researchers that the tubenose did not pose a serious threat.

“We figured it probably wasn’t going to have much of an impact on the Great Lakes fish populations,” Jude said.

The researchers were right. But the tubenose find still made the local newspaper.

“Not long after the [Detroit] Free Press article I got a call from a Canadian,” Jude recalled. The man said that his daughter had caught a fish that looked a little bit like the fish in the newspaper. They were keeping it alive in a goldfish bowl.

Jude had already received numerous calls reporting additional sightings, but so far they had all turned out to be mottled sculpin, a native species. Still, just to be thorough, Jude took the ferry to Canada.

“I went into his house and down in the basement, and here’s this giant fish. And I thought well, that’s not a tubenose goby.” Jude brought the fish back and once again took it to Smith.

Smith identified this one as a round goby.

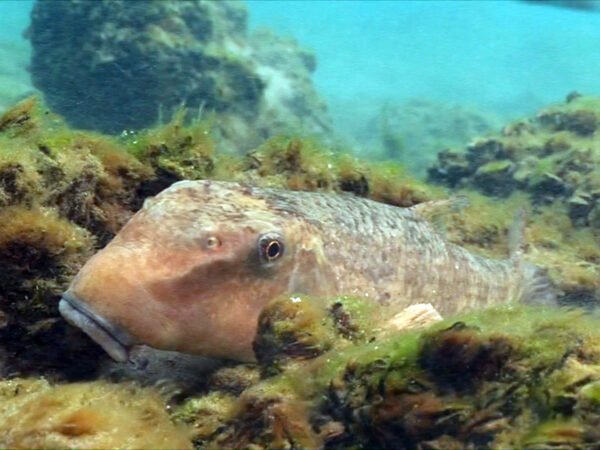

A round goby eats a zebra mussel. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

“The round goby was a different story,” Jude said. Round goby were known to be very aggressive and had successfully expanded their range when accidentally introduced into river systems in Europe.

“We were very concerned about it expanding its range into the Great Lakes,” Jude said.

As it happened, their expansion would be aided by the same industry that introduced them.

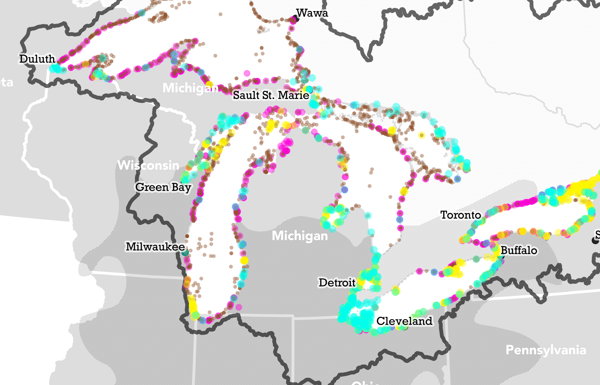

From the St. Clair River, the round goby next appeared in the Grand River in Northwestern Lake Erie. Except, none were found in between. A little investigation revealed that once again the goby had been transported by ship, in this case by a lake freighter making a regular run between the St. Clair and Grand rivers.

It was not long before round gobies were transported all the way to the Calumet River in southern Lake Michigan and as far as Duluth in Lake Superior.

“They showed up at each of these harbors all the way across the Great Lakes,” Jude said.

Within five years of their arrival in the St. Clair River, freighters had delivered round gobies to all five of the Great Lakes.

After the round goby discovery, Jude received a federal grant to study their impact and we joined his research team. Our job was to document the round goby’s behavior in the wild and provide the researchers with real-time feedback on how the natives were responding.

At one point, we found a new nest and dove the site every day for 32 days in a row, which is how long it takes for the male to rear a brood. Some days we did multiple dives documenting nest guarding behavior and offspring development.

After two seasons of dedicated observation, we came to view the goby in a new light.

They are a remarkably resourceful fish that took full advantage of the lack of predation to rampage the Great Lakes like marauding Vikings, so I get why they have been villainized. I just do not think that is a completely fair assessment.

Round goby were not stowaways. They didn’t intentionally sneak on board a freighter bound for the United States in an attempt to escape the Black and Caspian seas. It’s more accurate to say they were kidnapped or even abducted.

The most likely scenario is that the tiny larvae were just floating in a harbor minding their own business when a freighter sucked them up and literally shipped them across the world. Their ability to survive and even thrive is one of the reasons Gobiidae are the largest family of marine fishes in the world with 1950 documented species.

Kathy Johnson holding a round goby (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Goby are found in all types of habitats from coral reefs and brackish bays to freshwater rivers. One species of goby in Hawaii can even climb waterfalls over 300 feet high.

My admiration of gobies puts me in good company. The Emperor Emeritus Akihito of Japan is also a world-renowned ichthyologist who specializes in goby research. The Emperor is said to have a deep affinity for gobies and has personally identified 10 new species.

Round gobies have a cute facial structure with downturned lips that gives them a pouty expression I find oddly appealing. It reminds me of Oscar the Grouch from Sesame Street. And while their aggressive nature is bad for native species, it emboldens them to sit in the palm of my hand with only a bit of coaxing.

It’s hard not to bond with a cute fish nestled in your palm.

I remember diving off the St. Clair boardwalk in the late 1990s and feeling completely hopeless. The river bottom was a solid blanket of zebra mussels over which schools of round goby swam and nothing else. I feared the entire river would eventually reach a similar lack of diversity.

For a good 10 years, we watched them spread unchecked.

Thankfully, my worst fears and the direst of expert predictions were not realized.

The round goby and zebra mussel introductions changed the Great Lakes forever, and both are here to stay. But 30 years later, the Great Lakes are coping far better than most expected.

Last summer, I was enjoying a leisurely river dive in Marysville, Michigan. The previously unremarkable dive suddenly turned memorable when I realized what I wasn’t seeing. There were still lots of little gobies, but I saw almost no big ones!

I’m usually an optimist, but my younger self could not imagine a future where round gobies did not own the bottom. I’m so happy I was wrong.

The St. Clair River is a testament to nature’s ability to adapt. I do not remember the exact moment I saw my first round goby, but I will never forget the dive when I realized the river I know and love, while different, has retained its amazing diversity.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Playing peek-a-boo with the ducks

I Speak for the Fish: Logperch rocking, rolling and rebounding

Featured image: Kathy Johnson holds a round goby while diving. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

1 Comment

-

I wish you presented the available research on the debilitating affect this and other invasive species have done to our perch stocks,