When it comes to dealing with Michigan’s regulators on environmental justice issues, Detroit environmental law attorney Nick Leonard wants to change the narrative.

Too often when confronted with decisions that impact environmental justice communities, regulators focus on limitations and what they can’t do, Leonard recently told Great Lakes Now.

But he wants to flip that script so agencies like Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy focus on the possible with an emphasis on substantive outcomes for embattled communities.

Leonard is executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center and arguably his biggest recent challenge has been the Benton Harbor drinking water crisis.

Leonard helped lead a broad coalition of citizens and advocates that secured an intervention by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that was similar to the agency’s intervention in Flint.

Leonard recently spoke with Great Lakes Now’s Gary Wilson where he discussed the shortcomings of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s environmental justice initiatives. He also pointed out the systemic flaws in protecting EJ communities best illustrated by the “massive” effort it took in Chicago to deny a bad permit.

The interview was conducted by phone and email and was recorded, transcribed and edited for clarity and length.

Great Lakes Now: Taking office after the Flint water crisis, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer put an emphasis on environmental justice. Since, you led a coalition that secured the U.S. EPA’s intervention in the Benton Harbor water crisis. And EPA recently announced a civil rights complaint investigation over approval of an emissions permit in a majority-Black neighborhood in Detroit. Is there a pattern of failing to prioritize environmental justice by the Whitmer administration?

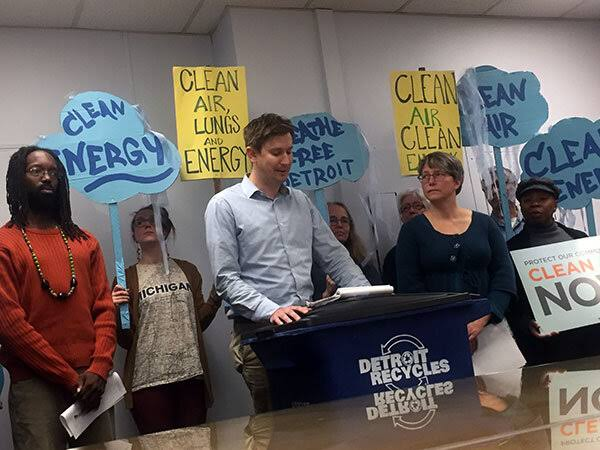

Nick Leonard, executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center (Photo courtesy of GLELC)

Nick Leonard: There’s certainly a pattern of failing to deliver on what environmental justice advocates expected from this administration that said it was prioritizing environmental justice.

What advocates envisioned were changed realities in environmental justice communities, changed substantive outcomes, such as reducing environmental risk in EJ communities. In some cases like Benton Harbor, making sure they’re not subject to environmental repercussions like high levels of lead in their drinking water. We haven’t gotten there yet in Michigan.

The actions of the Whitmer administration have been procedural and administrative in nature, things like establishing the Office of Environmental Justice Advocate within the EGLE. She established the Advisory Council on Environmental Justice, of which I’m a member, to advise EGLE on EJ issues.

At various other points she has sprinkled in references to EJ, as in the climate plan and things of that nature. What we don’t have is something to point to on the ground in the community that says, ‘This is different than it would have been under past administrations.’ Like, this outcome is different and as a result this community is enjoying better protections from environmental risk. That’s ultimately what we’re after.

Procedures are only as good as the better outcomes they produce. We’re short on better outcomes as it relates to EJ. And every state and even the federal government are struggling similarly. Michigan and the Whitmer administration aren’t alone in that shortcoming.

GLN: In general, EGLE director Liesl Clark’s defense on these issues is that the agency follows the law and it doesn’t have the authority to do more. Is that a legitimate defense? Or could she be more aggressive when it comes to protecting human health?

NL: We don’t think that’s a legitimate defense in all areas. Certainly EGLE is constrained by the laws it has to address these issues, there’s no doubt about that. We know what the reality is in Michigan, it is unlikely that our state legislature is going to adopt new laws that will aggressively address and further environmental justice. That’s our political reality.

So, when the Whitmer administration came into office, we spent a lot of time and energy trying to identify things that we thought EGLE could do without requiring a new statute or legislation. We pointed to specific existing laws and regulations where we thought they could do more.

But we haven’t seen the kind of aggressive action that we hoped for. Then we obviously urged EGLE to take a more proactive approach to ensure compliance with EPA’s Title 6 regulations, essentially the agency’s civil rights regulations. Similarly, we haven’t seen the aggressive action we hoped for there.

GLN: What is the role of Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services in EJ issues? This surfaced in the Benton Harbor water crisis where the agency had some visibility. Does it have a role and how’s it doing?

NL: MDHHS certainly has a role in Benton Harbor. It’s squarely focused on public health while EGLE is focused on questions of environmental law and regulation compliance.

We would like to see MDHHS play a large role and be more involved to be a stronger voice for public health in regards to environmental decision making. What we’re finding is that EGLE is not comfortable in that role and that EGLE’s decisions aren’t always accounting for and involving public health considerations. There’s a large role for MDHHS to play.

GLN: In a recent high-profile environmental justice fight in Chicago, community activists engaged in a hunger strike to prevent the city from granting a permit that could have further degraded air quality. EPA Administrator Michael Regan personally engaged on the issue, and the permit was recently denied by Chicago’s mayor. Is there a lesson to be learned for Michigan and other states from this outcome?

NL: I think there is. There are two lessons to be learned.

One is the amazing amount of effort it takes to change decisions involving environmental justice issues. You mentioned that in Chicago there was a very robust community-organizing component, a hunger strike, countless hours put in by advocates to get that decision changed. There was involvement from the EPA administrator. There was a lot that went into it.

One lesson to be learned from that effort is: how do we get to a place where these things don’t take these monumental efforts, where the issues raised by the advocates are just part of the process, where it won’t have to be this ad hoc process where organizers had to create this environment to get the decision maker consider the things that lead to a denial of the permit. How can we ensure that EJ considerations are simply what’s necessary for a company to do business?

A second lesson is to be skeptical of regulatory departments that say, ‘Our hands are tied. There’s not much we can do.’ We find there are often things that can be done, it’s just to what extent are the decision makers going to make that push and explore all there is that would allow a different decision.

And that massive effort previously mentioned from EJ advocates is not sustainable.

GLN: Environmental justice communities face an uphill fight. They’re dealing with dispassionate bureaucracies, laws that favor industry, and elected officials who tend to promise more than they deliver. What’s your advice for advocates and EJ communities on how to proceed from here?

NL: If you can get a state legislature to buy in on environmental justice issues and get key political actors to make EJ a priority, progress can be made. State legislatures can pass laws that direct state agencies to do more about environmental justice.

Or a governor could come along and create substantive, serious directives for their environmental departments and push them to move on EJ and get to those substantive outcomes I mentioned earlier.

Ultimately, I think we need to create a massive culture shift within our federal, state and local environmental agencies to get them to realize the role they play in addressing our nation’s history of race-based discrimination.

We use the short-hand of environmental justice, but it’s important to be clear that environmental justice is a movement that’s essentially seeking to address the environmental manifestations of our nation’s long history of racism. What we know about this history is that it is self-perpetuating, and unless we take strong, decisive action to cut it off, it will continue to grow and impact future generations.

Environmental justice advocates know this, and community members know this. We need the people working within our environmental agencies to know this and ultimately for them to own the problem and commit to addressing it holistically.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Canada’s Maude Barlow chronicles 40 years of activism in new book, “Still Hopeful”

Featured image: Great Lakes Environmental Law Center executive director Nick Leonard speaks at at event. (Photo Credit: Great Lakes Environmental Law Center)