By Kelly House, Bridge Michigan

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan; Circle of Blue; Great Lakes Now at Detroit Public Television; and Michigan Radio, Michigan’s NPR News Leader; who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work HERE.

Climate change is irreversibly damaging global ecosystems, economies and human health and wellbeing, according to a landmark report published Monday, and experts say Michigan won’t emerge unscathed.

Monday’s report, authored by a team of scientists from around the globe, outlines the risks of continued dependence on fossil fuels, and warns that society is failing to take steps that could limit human suffering amid worsening floods, fires, droughts and other climate extremes.

The report takes a global view, noting that the poorest nations — which tend also to be those least responsible for greenhouse gas pollution — will suffer first and worst. But experts from the Great Lakes region noted the pattern holds true locally, too.

Look no further than the toll of last summer’s metro Detroit floods on those who lack insurance to replace their destroyed belongings. Or recent Great Lakes high water levels that destroyed homes along Michigan’s coasts. Or the boil water advisories in some Ontario indigenous communities, which one expert said could get worse as warming temperatures increase the risk of pathogens. Or the reality that poor and minority Michiganders are more likely to live in close proximity to air pollution.

Mohammad Al Hajmoussa of Dearborn holds a door he pulled from its hinges after it was ruined during a “thousand-year” storm that filled his basement with chest-deep water. (Bridge photo by Kelly House)

Sapna Sharma, a biology professor and expert on global climate impacts at Toronto’s York University, is studying the uneven toll of climate disruption in the Great Lakes region. She said the disparities will grow worse as climate change progresses — unless places like Michigan act now to prepare for the coming disruptions.

“This is an issue that can and should be fixed immediately, before even further degradation of our communities, and further degradation of the infrastructure,” Sharma said.

The Great Lakes region is comparatively fortunate, climate experts said, because its expected climate disruptions are more manageable than, say, worsening western wildfires, rising seas or prolonged drought.

Instead, said State Climatologist Jeffrey Andresen, worsening rainstorms are the region’s biggest threat. But there’s a solution: Overhauling our infrastructure to better absorb floodwaters, thereby preventing the massive floods that have upended lives from Houghton to Midland to metro Detroit and inflicted billions of dollars-worth of damage in recent years.

“We have to build more capacity into the way we drain water off of the landscape,” Andresen said. “And that comes at a cost.”

In southeast Michigan alone, leaders of the Great Lakes Water Authority estimate it will cost as much as $20 billion to make the region’s infrastructure capable of absorbing enough rainwater to avoid floods like the one that damaged tens of thousands of homes last summer. Planned work includes upgrading pipes that whisk away water and revamping the ancient pumping stations designed to prevent sewer overflows.

Monday’s report comes with more bad news on that front: World governments have set a goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), a task that would require the entire world to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. It’s a goal the world’s nations are collectively not on track to meet. And even if they succeed, climate-fueled extreme weather events are expected to increase fourfold by century’s end.

There are other troubling statistics in the Great Lakes region, too:

- 5: That’s the per-decade, percentage-point decline in annual Great Lakes ice cover since record keeping began in the 1970s.

- 5,679: Number of Northern Hemisphere lakes that will permanently lose winter ice cover this century if fossil fuel use continues unabated (including many in the Great Lakes region).

- 16: Fewer days of annual frost annually, compared to 1951.

- 684: Driving miles from Marquette to Louisville, Ky. If humans fail to curb emissions, scientists say the U.P.’s climate – and the plants capable of thriving there – will be akin to present-day Kentucky by century’s end.

Sen. Adam Hollier, D-Detroit, is part of a contingent of Democratic lawmakers who have proposed a $5 billion climate preparedness spending plan for Michigan. He said he has noticed more acknowledgment of climate change in Lansing in recent years as Michiganders begin to experience the consequences, from flooded homes to shortened ice fishing seasons, and demand action from their elected representatives.

“Some people still want to argue about why” change is happening, he said, “but I don’t think that makes a difference when you lost everything in your basement, when your home lost $60-$70,000 worth of value or you lost the photo album of your grandmother, or your wedding dress, or the things that make your life precious.”

House lawmakers are considering a proposal to spend $3.3 billion on water infrastructure, including efforts to reduce flooding and sewer overflows. And while Republican Legislative leaders have not explicitly framed the discussion in terms of climate preparedness, a spokesperson for Senate Majority Leader Mike Shirkey told Bridge Michigan last year that Michigan’s infrastructure “needs to be able to withstand 200-, 500-, 1000- year weather events.”

A spokesperson for Shirkey did not respond to a request for comment Monday. A spokesperson for House Speaker Jason Wentworth said Wentworth “hasn’t had time to review” the water spending proposal.

Beyond shelling out money for preparedness, regional climate experts said, Michigan and the rest of the world should be sprinting toward a post-petroleum future. The authors of Monday’s global report warned that society risks missing “a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all.”

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has set a goal to make the state carbon-neutral by 2050. A state task force will soon release a final report outlining the steps Michigan should take to achieve that goal.

At the national level, legal and political resistance has hobbled President Joe Biden’s climate agenda.

Key climate provisions were cut from the federal infrastructure bill as Congress whittled Biden’s original $2.25 trillion proposal down to $1.2 trillion by the time the bill passed in November. The U.S. Postal Service last week finalized plans to purchase up to 148,000 gas-powered mail trucks instead of the electric vehicles Biden has pushed. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in a lawsuit by Republican-controlled states seeking to block the EPA’s ability to regulate emissions from the electricity sector.

And gas price spikes caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have sparked an oil industry lobbying push for more domestic drilling.

Andresen, the state climatologist, said he still sees reason to believe society can act fast enough to avert the worst impacts of climate change.

But he added: “This report is reminding us we’re really running out of time.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Even in water-rich Michigan, no guarantee of enough for all

Risky Drinking Water Pathogen Has Outsized Effect on Black Americans

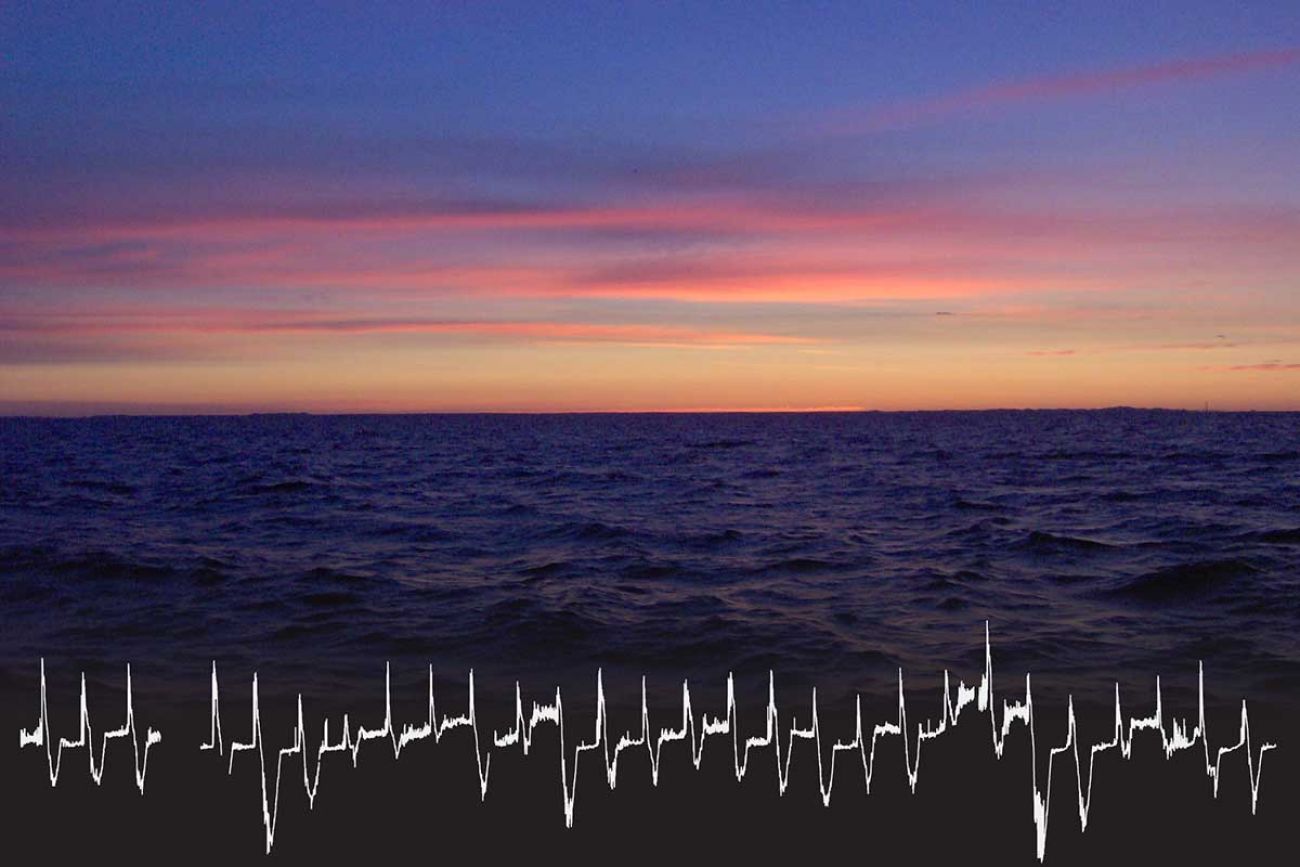

Featured image: A National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration study found that Lake Michigan’s depths, at 361 feet, have warmed 0.11 degrees Fahrenheit per decade in the past 30 years. The seasonal temperature variations in the lake’s water look similar to the markings on an electrocardiograph. (Courtesy of NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory)