This article was republished here with permission from Great Lakes Echo.

By Danielle James, Great Lakes Echo

Great Lakes invasive species cling to shipments and navigate canals to migrate, but one aquatic invader – sea lamprey – benefitted from border closures instead.

In recent years, U.S. and Canadian crews jointly treat lakes and streams to kill the invaders, which can feed on and destroy 100 million pounds of Great Lakes fish each year, said Marc Gaden, the communications director for the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

But the pandemic border crossing crackdown meant that treatment programs were much harder to complete, Gaden said.

“It’s really hard to be a binational organization when the border’s closed,” he said.

Gaden said this is due to requirements that both US and Canadian crews be present for large lamprey treatments.

The result?

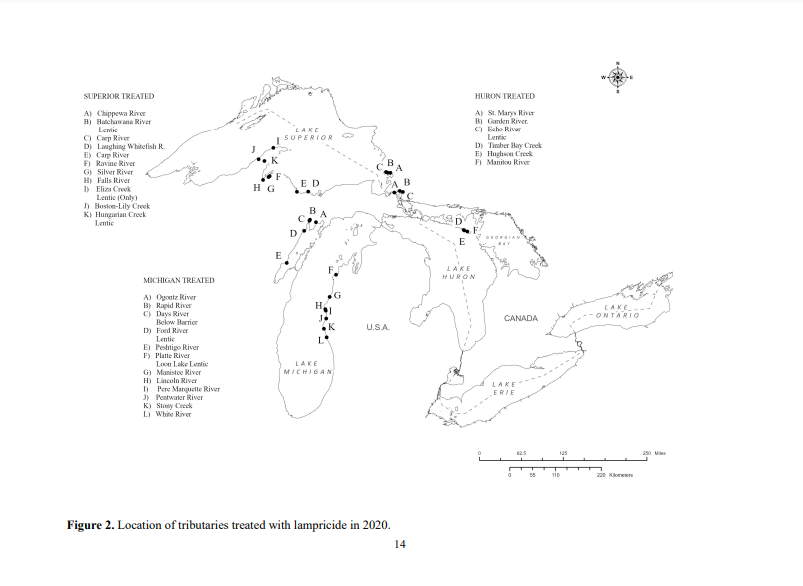

During 2020, 93 Great Lakes tributaries and 11 standing bodies of water were scheduled for chemical treatments for lamprey, according to research recently published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research.

Only 26 tributaries and six standing bodies of water were completed.

“We’ll know in a couple of years if the smaller number of treatments is going to lead to a big spike or a blip in lamprey numbers,” Gaden said. “We are anticipating a spike because of the number we had to defer, but we also think that the luck made us as well-positioned as possible.

Sea lamprey populations have been a concern for researchers since they entered the Great Lakes from the Atlantic Ocean through shipping canals in the 1920s. They spread quickly and had a detrimental effect on fisheries, Gaden said.

“They’re the perfect storm of invasion because the sea lamprey found an unlimited food supply, abundant habitat for spawning and there’s nothing that keeps them in check,” Gaden said. “They have no predators in this system of any consequence.”

“All they do is eat and spawn until they die,” Gaden said. “They’re very good at it.”

A fish with a sea lamprey bite is shown next to the invasive species. (Photo Credit: Great Lakes Fishery Commission)

Lamprey feed off Great Lakes fish by puncturing holes in their side and draining their body fluid. Each lamprey will kill approximately 40 pounds of fish until they spawn, Gaden said.

The large lamprey population killed many times the commercial catch of native fish, at a time when fisheries were already stressed due to overfishing and lack of regulations.

“They’re vampires,” he said.

Both the US and Canada attempted individual control programs, which proved ineffective, Gaden said.

Then, in 1954, the US and Canada created the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, a collaborative effort to treat and limit sea lamprey populations in the Great Lakes.

“We knew lamprey control was going to need a border-blind combined US and Canadian effort,” Gaden said. “It requires boots on the ground, boats in the water and it requires that the US and Canadian lamprey control crews work together.”

When these crews can’t work together, problems arise. In 2020, crews were limited to day trips, meaning they did more small and nearby treatments than usual.

In Lake Michigan, 11 streams and two standing bodies of water were treated, according to a 2020 report to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission. But 28 streams and two standing bodies of water were scheduled and not attempted because of pandemic travel restrictions.

Ten streams and two bodies of water were treated in Lake Superior, but 20 tributaries weren’t attempted due to border closures or low water.

In Lake Huron, five Canadian tributaries were treated, but 11 were deferred and two standing bodies of water weren’t treated.

Lake Erie and Ontario were not treated at all by the commission, according to the report.

Gaden said Canadian crews typically treat both sides of Lake Ontario.

“If they couldn’t cross over, it was difficult or impossible for crews in Michigan to go out and do those treatments,” he said, “especially given that they could only do day trips.”

Gaden said partners near Lake Champlain and the Finger Lakes in New York were able to pick up the slack on the U.S. side of Lake Ontario.

He said increased funding and more treatments before the pandemic also helped the commission stay on track.

“U.S. and Canadian crews had been pretty aggressive with treatments leading up to 2020,” Gaden said. “We actually had been ramping up because of increased funding, so we were ahead of the curve going into 2020.

“We had wiggle room in treatments. We could defer some. That was lucky,” he said.

But researchers who published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research still anticipate that pandemic constraints will result in more juvenile sea lamprey and an increase in sea lamprey attacks.

Gaden said it takes several years for the survivors of treatments to return to spawn, so researchers won’t immediately know the impact of deferred treatments.

“We’ll know in a couple of years if the smaller number of treatments is going to lead to a big spike or a blip in lamprey numbers,” he said. “We are anticipating a spike because of the number we had to defer, but we also think that the luck made us as well positioned as possible.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

New Ontario watercraft regulations fight invasive species

With new invasive carp money, the Great Lakes learns from past invasions

Featured image: The locations of tributaries treated with lampricides in 2020, according to an annual report to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission. (Photo Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Fisheries and Oceans Canada)