For Professor Nancy Langston, our intransigence in protecting struggling species like caribou and others is a puzzle. These species exist in our memories and culture, and we’ve invested in protecting them, so why do their populations continue to crash?

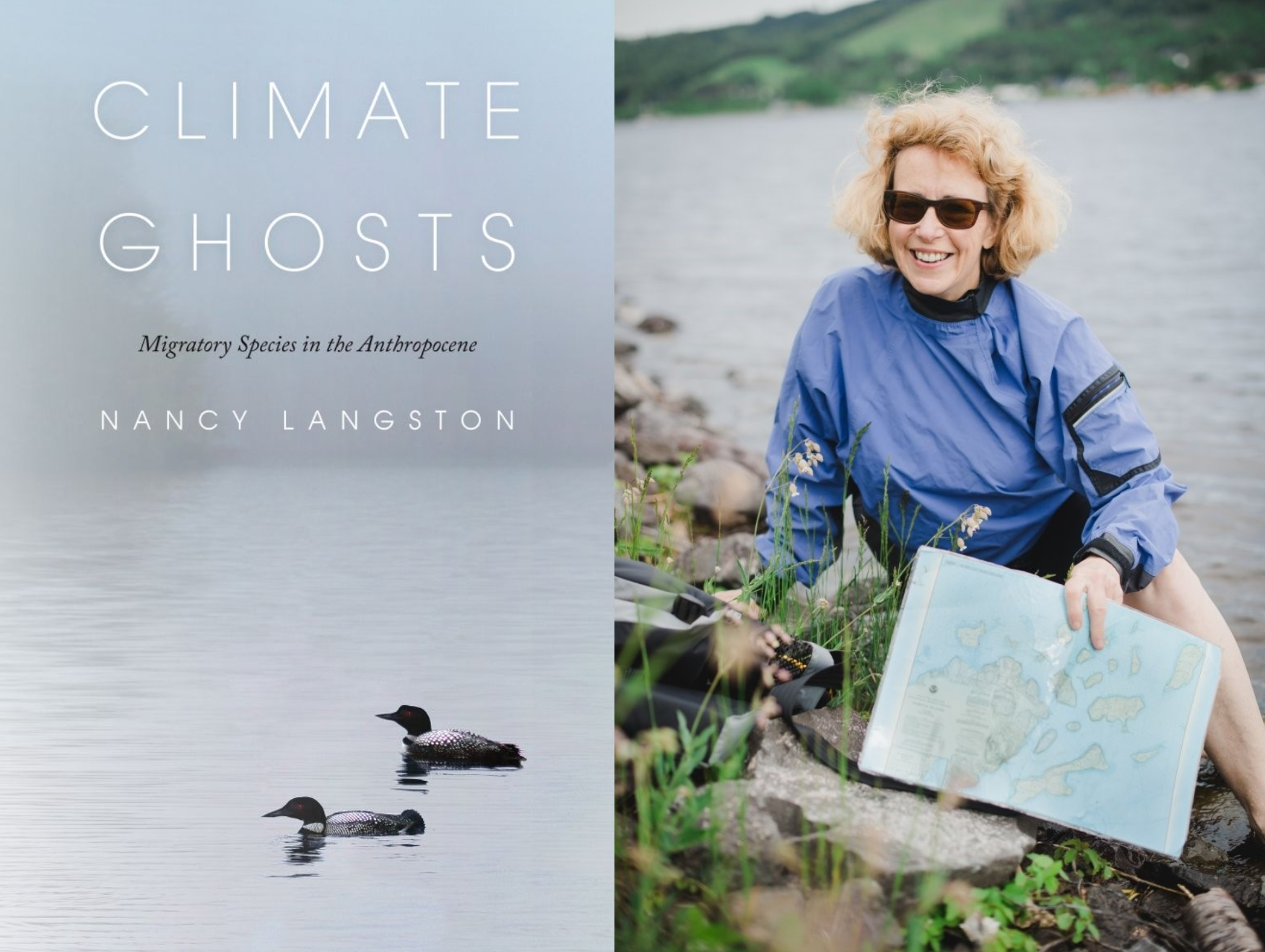

That’s the question at the core of Langston’s latest book, “Climate Ghosts: Migratory Species in the Anthropocene”. Langston is an environmental historian at Michigan Tech University in Houghton, Michigan.

Great Lakes Now’s Gary Wilson recently talked with Langston about Climate Ghosts and the need to merge Indigenous people’s scientific and cultural practices with traditional western scientific techniques. Langston explained “two-eyed thinking” and how an over-reliance on collaborative practices can inhibit restoration efforts.

Langston also shared her thoughts on the status of Lake Superior and U.S. and Canadian relations concerning the lake, with the Line 5 dispute between Michigan and Canada looming in the background.

The interview was conducted by phone and email and was recorded, transcribed and edited for clarity and length.

Great Lakes Now: What are climate ghosts and why write about them now?

Nancy Langston: Climate ghosts are individuals or species that are on the verge of extinction or whose populations are crashing. They’re species that some biologists call endlings. They can be restored, but it would take an enormous amount of effort. So, these are species where we still have traces of their DNA remaining in fragmented populations. But often they’re three female caribou roaming the Selkirk Mountains in Idaho with very little possibility of ever finding a mate.

These are species that are still present in our memories, in petroglyphs and place names all around the basin, but they’re species that are on the verge of being forgotten.

I wrote Climate Ghosts and chose three different migratory species: a bird, the common loon; a mammal, the woodland caribou; and a fish, the lake sturgeon. Three species that people have been trying to restore for well over a century. Yet, there’s a puzzle. People love them, and we’ve invested a huge amount of energy and economic resources into restoring them and they’re still struggling.

So, the puzzle I address is why has restoration failed to restore resilient populations. My argument is that in order to have better futures for these species, we need to look at the history of restoration efforts in order to devise better and more resilient strategies for the future.

GLN: At the core of Climate Ghosts is your premise that humans need to expand their view of the natural world to blend science and cultural practices. And to include what Indigenous communities call “two-eyed seeing.” What is meant by two-eyed seeing?

NL: Two-eyed seeing is the effort to combine western scientific techniques and perspectives and insights with Indigenous scientific and cultural practices of thinking of other species as our kin. Taking them seriously as relatives and as individuals with their own agency. Rather than focusing primarily on populations, which is super important, it combines a way of looking at population ecology while also paying attention to the individual animals.

GLN: Related to the natural world, your colleague, Western Michigan University Professor Lynne Heasley wrote in the foreword to Climate Ghosts that “western society has anointed western science as the pinnacle of knowledge.” Is that still the prevailing view?

NL: I love Professor Heasley’s foreword to Climate Ghosts, but I disagree with her on that point.

I was trained as an evolutionary ecologist and did my PhD research in avian ecology, working in Zimbabwe. I really value western scientific perspectives. I’m in love with creating hypotheses that can be refuted, setting up experimental and observational tests of these hypotheses. One of the great things about western scientific perspectives and techniques is that we’re taught to understand that our preconceived notions of the world can shape what we see and measure. To avoid cherry-picking data that confirm your own biases, you start with close observations, then design falsifiable hypotheses and set out to refute them. I wish people took that more seriously. I would like to see more scientific empiricism guiding our decisions about restoration ecology and our decisions about which policies make the most sense in a particular context.

The two-eyed seeing that Professor Healey and I urge also starts with that close observation of the world but also urges us to pay attention to individuals of other species as kin. Both ways of seeing can help us be surprised by what we learn about the world outside of our own particular perspectives. Both are essential in a sustainable future.

GLN: In the book you said that participatory management and collaborative practices are widely used today in restoration efforts. If there is one word that describes the Great Lakes restoration process, it’s collaborative. But you caution that participatory and collaborative practices can also provide ready excuses to delay hard decisions that might anger key constituents. Can you elaborate?

NL: I applaud the ecosystem system management perspective, trying to understand that there are multiple stressors affecting any ecosystem. But I’ve seen over and again in the historical record and also in modern management the need to include all participants, the need to take all perspectives seriously, while valuable can also mean that we delay decision-making for decades in a way that we no longer have to make a decision.

One example is when a species is in crisis where there are only several individuals left. For example, the 18 individuals of the woodland caribou population that remained three years ago in the Lake Superior basin. The parks department in Canada wanted to do a full participatory management process and full environmental impact statement process before making any quick decisions about rescuing those individuals.

That whole process would have taken over a decade. While it’s important to start that process, to delay sending a helicopter in and rescuing some individuals to give a future for the population doesn’t make any sense. That’s a simple example of this impulse to do full participatory management meaning that there is not going to be anything to manage if you’re not careful.

There are plenty of other examples where, in the effort, say with the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement with the U.S. and Canada, the continuing decision to focus on the full ecosystem rather than to do forensic ecology and remove dioxin from pulp mills was really destructive both in the short and long run. Ecosystem management is critical to think about multiple stressors. But when a focus on them means that you’re not going to act on the stressor that’s about to drive a population to extinction in the next two weeks, it’s counterproductive.

GLN: By geography and profession, you are close to Lake Superior and wrote in your 2017 book, “Sustaining Lake Superior”, that people tend to see the lake as “outside of history; a place so cold, remote, and pristine that little has changed for eons.” Has that perception changed in the last five years?

NL: I certainly hope so. The perception that the lake is incredibly remote and pristine is problematic, because we stop paying attention to the global processes like coal consumption and carbon dioxide release that are leading the Lake Superior basin to probably be the fastest warming of all large lakes on Earth.

It’s not happening just because of local processes but because of global processes. In western discourse we have this idea that Lake Superior is impossibly remote and pristine, but for Annishinabe people it’s not at all remote. It’s been at the center of their economic universe, their trade networks, and their cultural and spiritual practices for generations. The lake is remote from industrial production if you measure it by distance, but it’s not remote in terms of atmospheric currents that bring toxics from distant shores to our wetlands.

And the extraordinary need we’re about to have for rare Earth metals and also for common minerals such as copper which are going to place enormous stress on the Lake Superior ecosystem.

GLN: With the seat of Great Lakes policy and power in Chicago and the Great Lakes media in lower Michigan where the majority of the population resides, does Lake Superior get the attention and resources it needs?

NL: Yes, we’ve actually done quite well in the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative’s sweepstakes. The EPA has tried hard to not ignore Lake Superior. We don’t have the human constituency that Lake Michigan has, and Lake Michigan is enormously important. If any of the lakes are overlooked, it’s Lake Huron that gets less attention than it probably should.

A lot of people across scientific communities look to Lake Superior as being this example of what the other lakes have a chance of aspiring towards. It’s possible to clean up enough of the toxic sites, to remove enough of the invasive species to make other Great Lakes as healthy as Lake Superior. I’m not sure that’s possible in a rapidly warming world where invasive species are expanding, but it’s a great aspiration.

But of course, Lake Superior would love to have more funding for restoration initiatives, and above all, we’d love to have more funding for green infrastructure. It’s really important to do restoration, but as I tell my undergraduate engineering students in our environmental policy classes, it is much less expensive to prevent pollution, flooding and climate change problems than fix them afterward. We’re spending a lot of money on restoration, and it’s time to spend money on infrastructure and protection to prevent restoration needs 20 years down the road.

GLN: Lake Superior is a shared resource and responsibility with Canada. What’s the state of the relationship between the U.S. and Canada on Lake Superior? Considering the backdrop of the tension between Michigan and Canada over Line 5 which has been elevated to the highest levels in Washington and Ottawa.

NL: Before the whole Line 5 disagreement and Canada’s efforts to enforce the 1977 pipeline treaty, in seeming defiance of much earlier treaties, I would have said it’s a fairly strong relationship. On the bi-national forum we’d have half Canadians and half Americans, and we met four times a year around the basin to listen to community concerns about projects that were on the verge of being permitted.

Then, Environment Canada was the first to cut our funding saying it wasn’t necessary and the agencies didn’t need public input that could have potentially prevented events such as Flint and Benton Harbor. Canada was the first to pull back from those agreements, and all along with the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreements, I think a lot of Americans think of Canada as being this great, conservation-oriented country to the north.

Canada has had many problems enforcing environmental protection like respecting tribal sovereignty and providing clean water for Indigenous communities. Canada has as many problems as the U.S. and that continues. So, while I was disappointed with Canada’s decision to object to Line 5 decommissioning and to defy the Tribes in Michigan, I wasn’t completely surprised by it.

Editor’s Note: 1/21/22 This story was update to correct one misspoken word.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Fresh, local and forgotten: On Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, families fight to save their fisheries

The next source of trouble for Great Lakes fish populations: tires

Featured image: Climate Ghosts cover; Nancy Langston photo by Sarah Bird / Michigan Tech

University