The seemingly endless process of crafting, negotiating and passing the infrastructure legislation is over.

The bill topped out at a trillion dollars, and $1 billion of that funding is coming to the Great Lakes region for continued restoration of the lakes. That’s in addition to the ongoing federal funding of over $300 million annually the lakes have received since 2010.

For a billion-dollar windfall, there’s no shortage of demand for a piece of the federal pie.

It comes from multiple constituencies, like members of Congress who want to bring funding back to their district, the various state agencies that are involved in much of the restoration work, and the non-profit environmental groups who have their own priorities.

The U.S Environmental Protection Agency oversees Great Lakes restoration, and Great Lakes Now recently asked the newly appointed regional administrator Debra Shore for her office’s priority for the funding.

“A significant portion of that increase will be dedicated to continuing work and accelerating clean up on the Areas of Concern in the Great Lakes, in particular cleaning up the contaminated sediment in these Areas of Concern,” Shore said.

Shore was referring to the multiple sites that remain on a 1987 list that includes a corridor containing the Detroit, Rouge and Clinton rivers in Michigan, and the Maumee River and infamous Cuyahoga River in Ohio.

With demand high for the funding, Great Lakes Now asked the EPA for priorities. Should specific sites like the Detroit River, with 3-4 million cubic yards of toxic sediment go to the front of the line? Or should the funding be parsed out evenly across the region?

EPA spokesperson Taylor Gillespie said the toxic sediment sites are “likely to be top priority” and agency management is currently reviewing various approaches. Gillespie did not provide a timeline to announce a plan.

Great Lakes Now canvassed the region for comments from constituent groups on whether any sites should be given a priority.

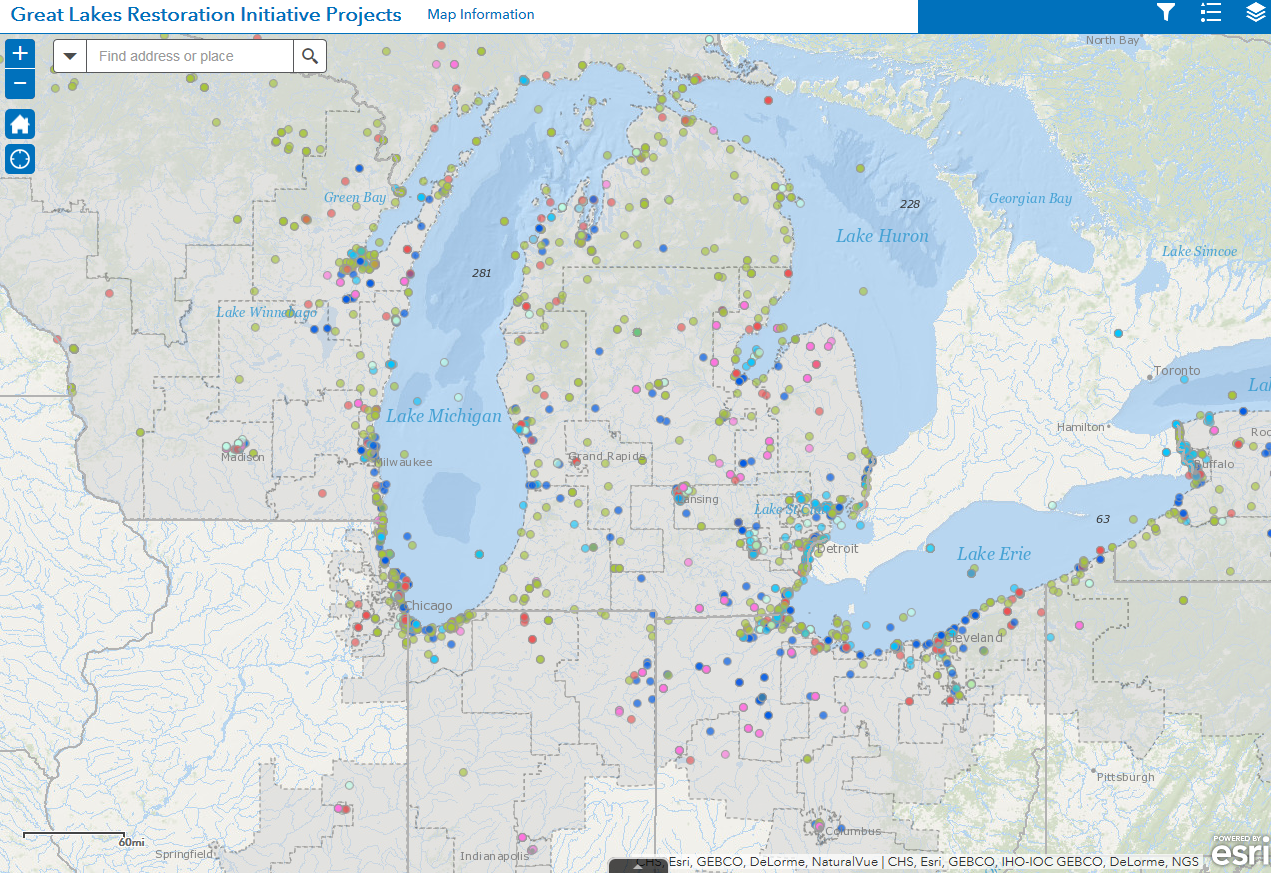

Great Lakes Restoration Initiative Projects (Image by glri.us)

Teresa Seidel at the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy is not in favor of designating priority sites to receive funding.

“It is important to ensure that work continues at all of the remaining Areas of Concern and the funding be available to all AOCs to ensure progress on implementing Remedial Action Plans,” said Seidel, who directs EGLE’s Water Resources Division.

Seidel said EGLE has worked with local AOC advisory councils and it’s important to demonstrate continued progress “to retain public support for the program.”

EPA expects the Detroit River AOC’s 3-4 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment to be cleaned up in 10 years, according to Chris Korleski, who directs the Great Lakes National Program Office that oversees the AOCs.

But EGLE aquatic biologist Sam Noffke isn’t that optimistic. Noffke said in September that the Detroit River has been the recipient of industrial waste for decades and clean up could take another couple of decades.

And in the meantime, the state of the Detroit River isn’t helped by seawall collapses and industrial spills that continue to happen.

The non-profit Friends of the Detroit River works with state and federal agencies on restoration projects and spokesperson Mickey Lyons told Great Lakes Now the group does not comment on how funds are allocated.

Great Lakes Commission Executive Director Erika Jensen praised the “dual investment” of the annual restoration funding and the $1 billion coming from the infrastructure legislation. The commission represents Great Lakes governors and premiers from Ontario and Quebec on issues important to the region.

Jensen said the two tracks of investment will accelerate cleanup of the AOCs while allowing for continued restoration on projects like habitat restoration and aquatic invasive species.

Jensen declined to provide a priority recommendation for specific AOCs for cleanup but said the commission will continue to work with the EPA and the states to identify projects that “maximize regional benefits.”

Ann Arbor’s Laura Rubin directs the non-profit Healing Our Waters Coalition and she expressed support for the EPA’s decision to focus on removing toxic sediment from the AOCs.

“Healing Our Waters supports the EPA’s approach” to spending the $1 billion, Rubin said. “There’s a huge need for sediment cleanup at the AOCs. They need a big investment.”

The infusion of infrastructure funding will free up money that can be used on climate issues, according to Rubin, who said it will also provide an opportunity to give greater emphasis to areas and people neglected in the past.

Rubin declined to recommend specific sites for cleanup.

The federal Great Lakes restoration program has invested $3.8 billion in the region since 2010 with approximately $1.2 billion directed to the Areas of Concern, according to the EPA.

In 2020, Congress extended the program until 2026, though funding has to be approved annually and is subject to the uncertainties of the budget process. In 2010 it was funded at $475 million but was cut to $300 million under congressional pressure to reduce federal spending in President Barack Obama’s 2011 budget.

Former President Donald Trump tried to eliminate all funding for Great Lakes restoration, but Congress blocked that attempt.

The GLRI is modeled after similar programs for the Everglades and the Chesapeake Bay that started in the early 2000s.

Florida Republican Sen. Marco Rubio requested $5 billion for the Everglades from the infrastructure bill, but the funding was not included in the version that passed.

Since, members of Florida’s congressional delegation have written to the Army Corps of Engineers requesting the $5 billion to be included in its work plan. The Army Corps has until Jan. 14, 2022, to submit its plan to Congress.

Separately, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis recently announced his 2022 budget proposal includes $960 million for Everglades restoration.

Michigan does not have a line item in the state budget for Great Lakes restoration similar to Florida’s, EGLE spokesperson Scott Dean told Great Lakes Now. The funding Michigan receives for AOCs comes from the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and tends to be used for habitat restoration, according to Dean.

Federal funding Michigan receives for toxic sediment clean up requires the state to provide partial funding to support the project, but those funds are no longer available.

“State bond funding to address toxic sediment sites from the Clean Michigan Initiative has been depleted and not replaced,” Dean said.

Restoration programs for the Great Lakes, the Everglades and the Chesapeake Bay are generally seen as mature.

GLRI is entering its 13th year and it’s not unusual for members of Congress to ask how much longer it will need to be funded, former Obama Great Lakes adviser Cameron Davis told Great Lakes Now.

The question assumes the Great Lakes are “fixable” like a car, according to Davis.

“We are past the point where the Great Lakes can take care of themselves without our intervention,” Davis said.

A complete list and the status of the Areas of Concern is at the EPA’s website.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Q&A: New EPA Great Lakes administrator talks Benton Harbor, infrastructure, AOC cleanup

Your Federal Tax Dollars: How they are funding the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative

In Perpetuity: Toxic Great Lakes sites will require attention for generations to come

Featured image: Chemical Valley in Sarnia, Ontario, sits on the St. Clair River upstream of drinking water intakes for several Detroit metropolitan municipalities. (Photo Credit: Lester Graham/Michigan Radio)