Shipping companies and ports around the world and on the Great Lakes are launching sustainability efforts to lessen their environmental impact, combat climate change, and improve their efficiency and images. With support from the Solutions Journalism Network, Great Lakes Now Contributor Kari Lydersen is reporting the four-part series “Sustainable Shipping.”

Read them here:

At the Port of Milwaukee the wind blows toward a greener future

Burns Harbor port tries to green Indiana’s industrial coast

And watch for the “Sustainable Shipping” segment in Episode 1031 of the Great Lakes Now monthly program.

When zebra mussels emerged as a dire ecological and economic threat across the Great Lakes in the 1990s, it was a wakeup call that the existing patchwork of international, state and federal regulations were not protecting the delicate ecosystem, the source of drinking water for millions of people.

In response, some industry leaders came together to form a voluntary sustainability certification organization called Green Marine.

Founded in 2007, today it counts more than 150 port authorities, port terminals, shipping companies and shipyards as members who have committed to improving their environmental record on issues like air emissions, spills, community relations and more.

Since its formation in the Great Lakes region, Montreal-based Green Marine has expanded to include members on the U.S.’s East, West and Gulf coasts as well as in Europe.

Since its formation in the Great Lakes region, Montreal-based Green Marine has expanded to include members on the U.S.’s East, West and Gulf coasts as well as in Europe.

Demanding sustainability in shipping is challenging, as the players – ships, ports and other entities – come from multiple countries and states with varying regulations, working in a highly competitive sector.

As a voluntary program, Green Marine encourages its members to adopt best practices and rewards them with different levels of certification that can help in gaining increasingly important support from the public as well as regulators and funders. This can be especially important for port authorities, which are often located in urban areas and need approval or funding from government entities for their operations.

The founding members of Green Marine – including ports in Montreal, Duluth, Milwaukee and other cities – have intended to serve as models. The idea is that, along with motivating ports to become more sustainable and earn a higher rating, the network created by Green Marine helps ports and shippers learn from their peers about innovations and sources of funding.

“Green Marine provides a framework and some discipline,” said Daniel Dagenais, vice president of operations at the Montreal Port Authority, which aside from the Port of Seattle is the only port to earn a perfect score from Green Marine. “You can only improve what you measure. We can offer a green dock and have objectives, but if we’re not measuring our progress, measuring all the dimensions of sustainable development, how can we say we are better today than five years ago?”

How it works

Green Marine membership entails committing to meet at least baseline regulations – represented by a score of one out of five in given categories – and continuing to improve.

Ports receive scores in areas including spill prevention, waste management, community relations, air emissions and environmental leadership. (Categories are slightly different for ships and port terminals). A score of two in the air emissions category, for example entails reducing truck idling and issuing warnings to ships that emit excessive smoke. A score of five requires publicly disclosing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing those emissions by at least 1% per year

To join, a member must have at least one level 2 score, and they are required to move up one level on at least one indicator each year until they have all level 2s.

David Bolduc, Green Marine executive director (Great Lakes Now Episode 1031)

“There is no obligation to improve beyond level 2, but since the program is constantly being updated and reviewed to maintain our requirements beyond regulation, participants have no choice but keep improving to maintain their levels,” said Green Marine executive director David Bolduc. A few members have lost their certification over the years because they did not meet the improvement mandate.

“We have gigantic ports with hundreds and hundreds of employees – they have more capacity to get to level 5 everywhere,” said Bolduc. “For other smaller ports it will be more challenging – for them level 2 or 3 are great.”

Members self-report their plans, actions and progress annually, and independent verifiers enlisted by Green Marine visit members every two years to confirm their reports.

Bolduc said that “when ports join the program they commit to go above and beyond” government and international regulations. “The program itself is a work in progress, we review our requirements every year as regulations change, and there are new technologies to take into account.”

Environmental and business groups and government agencies – like the Environmental Defense Fund and Waterfront Alliance – are also Green Marine partners and supporters, and they advise on the goals for ships, ports and in-port terminals for commodities like oil, steel and grain.

Green Marine also undertakes studies and makes recommendations related to policy, funding, technology and best practices. In one example, the organization prepared a comprehensive July 2021 report for the Conference of Great Lakes St. Lawrence Governors & Premiers.

“That’s what distinguishes Green Marine from other recognition schemes, it’s like a partnership, a long-term dialogue between the shipping industry and stakeholders,” said Bolduc. “There can be suspicion when you hear of a voluntary industry program. If you want to convince an environmental group this is serious, you have to make a real effort to include them in the process, to have real transparency.”

Ports are expected to keep improving their scores to maintain certification, though there is not a specific mandate that they do so.

“It’s not just, ‘Oh, you’re certified as a level 2 or level 3 and you can rest on those laurels,’” said Adam Tindall-Schlicht, director of The Port of Milwaukee, which has three 2s and two 3s on its latest report. “By having sophisticated steps, it does allow Port of Milwaukee a vision for taking those next steps, a roadmap for continuous improvement.”

Related stories on Great Lakes Now:

Stalled Ships: Shipping industry looks to infrastructure investments to boost demand

‘The water always wins’: Calls to protect shorelines as volatile Lake Michigan inflicts heavy toll

Complicating factors

Reducing emissions of greenhouse gases and the particulate matter, sulfur dioxide and other compounds that endanger public health is arguably one of the most important goals for ports. It’s also one of the most difficult.

“First step is you need to know your emissions, have an audit,” said Bolduc. “Then you need to find ways to reduce your impact, that’s where it can become more complicated quickly. If you really want to reduce emissions significantly it will require new technologies that may not be so easy to implement – like shore power, electrification.”

While ships are in port, they typically continue burning dirty fuel in order to keep the lights on and systems operating on board. But it is possible to power a ship with electricity from the shore instead, referred to as shore power. The ports of Montreal and Milwaukee and other Green Marine members offer this option, but it’s not easy.

“You need to coordinate with a lot of different entities,” including the municipality and utility, said Bolduc. “The ships need to be equipped to be able to plug in to electric power. And you need to consider where the electricity comes from. If it comes from a coal power plant, maybe the gain is not so great.”

Controlling dust and reducing and treating stormwater runoff are also key priorities. Various options are available for both, though they can be costly and take real commitment to implement consistently.

Randy Helland, Green Marine verifier (Great Lakes Now Episode 1031)

Randy Helland, one of the verifiers contracted by Green Marine, noted that capturing stormwater is “particularly important at ports where there may be some residual oil or some residual product that is on the pavement and that would go into the storm drains and then eventually go into a lake or go into a tributary.”

As noted with greenhouse gas emissions, Green Marine puts much emphasis on measuring and planning. Members can move up the tiers in part by quantifying their emissions, for example, and making sustainability plans, even before actually doing anything concrete that will reduce their environmental impact.

When asked for this story, Green Marine member ports listed relatively few concrete physical changes they have made specifically because of being Green Marine members or with help from Green Marine.

Who gets to regulate?

Even if the criteria for Green Marine certification and advancement were stricter, there are of course limits to what a voluntary program can achieve. It’s hard for a port to invest massive amounts in environmental improvements, because they are competing with other ports in attracting ships and on-site tenants, limiting the costs they can pass on, and as quasi-public agencies they may have to justify expenditures to boards or commissions.

Many ports are “landlord ports,” wherein a government body or public-private entity rents space to transport companies and even manufacturers that operate within the port’s footprint. Tenants often include oil and gas companies; agriculture; shippers of bulk materials like salt, iron ore and coal; and steel operations. At such landlord ports, the bulk of environmental impacts likely comes from the tenants, and ports may be reluctant or unable – given various laws – to make demands of their tenants regarding sustainability.

There are international regulations governing ports, namely through the International Maritime Organization, as well as state and federal laws related to air and water emissions, noise, and other factors. Leaders at Green Marine and their members said that increased binding regulations are not necessarily a realistic or desirable way of achieving greater sustainability in the sector.

The passage of the Great Lakes St. Lawrence River Basin Compact limiting water diversion out of the basin is an example of how difficult it can be to pass such regulations. It took years to ultimately enact the historic agreement, involving ratification and legislation from the Canadian and U.S. federal governments, as well as the eight states and two provinces.

The effort to pass stricter ballast water regulations – to prevent invasive species disasters like the zebra mussel – is another example of the difficulty. The U.S. EPA, Coast Guard and multiple states have made their own often conflicting moves to regulate ballast, resulting in years of contentious debate and lawsuits.

A typical Great Lakes port also involves moving goods on truck, rail and barge, sectors that are hard for state or local governments to regulate.

Green Marine and member leaders said financial incentives and grants for individual projects and for research are often better ways to achieve sustainability improvements.

“We’d like to see more incentives and support in research and development in environmental technologies – that’s where governments can really help,” added Bolduc. “More regulations sometimes are necessary, especially to have a level playing field. We don’t like having very different regulations from one state to another, one country to another, especially in the Great Lakes where it’s one hydrographic system. But Green Marine shows that good progress is possible without regulation.”

(Graphic courtesy of Green Marine)

Encouraging open dialogue with local communities

In recent years, Green Marine has placed increasing emphasis on community relations.

Studies have shown many ports have major public health and quality of life impacts on surrounding communities, which tend to be disproportionately people of color and lower income. The diesel emissions from trucks, trains and ships that come through ports, not to mention dust and fumes from chemicals or commodities stored and made there, can have serious public health consequences for neighbors. Noise, traffic and lights from ports are also an issue.

A 2012 study by the Trade, Health and Environment Impact Project based at the University of Southern California for example found that the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles were the single biggest source of air pollution in southern California, with emissions contributing to asthma, reduced lung development in children, cancer and premature death. Environmental justice and community organizations on the East and West coasts have increasingly mobilized around these issues. The Great Lakes has seen less community activism and pressure, but the risks to the public are similar.

“Ports are the window of the shipping industry” to regular people, noted Bolduc. “They are located in urban areas most of the time. They are under scrutiny from different neighborhoods and the communities. They have to show even more than shipping companies that they care about sustainability, that they are proactive.”

He said that ports need to meaningfully involve community members in dialogue and actually listen to them.

“One thing the most advanced ports do is have a permanent committee open to citizens where they discuss port projects, potential impacts,” he said. “Ten years ago no one would do that, they would be too nervous. (Now) they realize in the long-term it’s much better to be transparent. There’s a big difference between an information session you do once every two years and a committee with constant interaction, where you talk about your projects before you start working on them.”

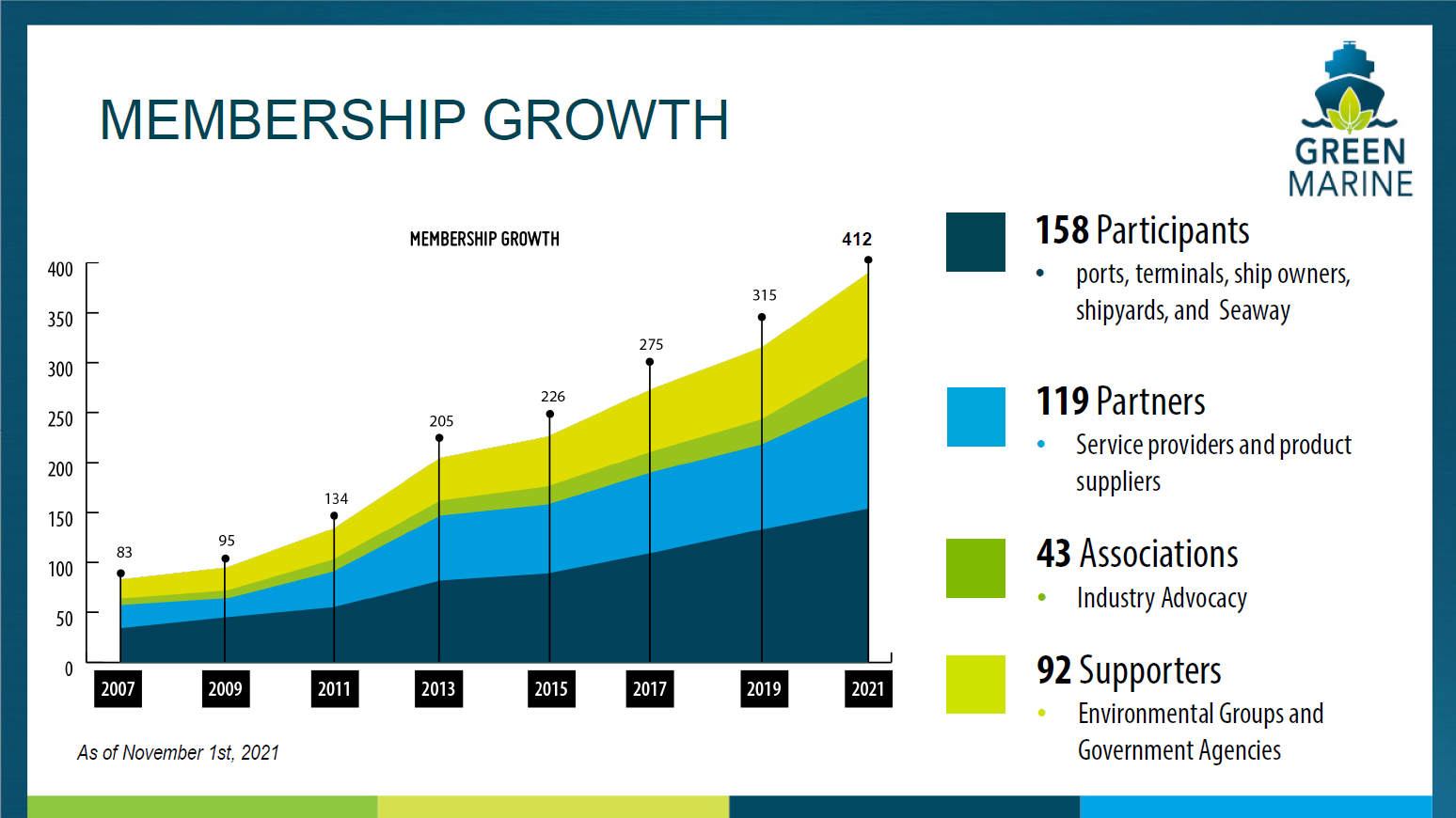

Green Marine’s total membership has increased steadily since its 2007 founding, growing from 34 participants who received certification to at least 158 today, and 412 total members today including industry associations and other partners.

Helland has worked in the maritime industry for three decades, including 16 years in the Coast Guard, on the Great Lakes as well as other coasts. He said the increasing interest in Green Marine is a sign of larger changes in the industry.

“I’ve seen the maritime industry as a whole embrace environmental excellence and really have a seriousness of wanting to comply – if not exceed – federal, state and local requirements,” he said. “This has been a great collaborative effort between the maritime industry, the governments, the interest groups, the environmental groups coming together and really forging a way ahead.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Duckling Docks: Toronto installs floating docks to save drowning birds

Canada expands ballast water restrictions to reduce invasive species spread

Featured image: Ports of Indiana – Burns Harbor (Great Lakes Now Episode 1031)