By Kelly House, Bridge Michigan

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan; Circle of Blue; Great Lakes Now at Detroit Public Television; and Michigan Radio, Michigan’s NPR News Leader; who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work HERE.

ALBANY, OHIO—When Mary Ellen Sementilli and her family moved into their creekside home in Ohio’s Appalachian region, the septic system worked like a charm. Which is to say, it was easy to forget it was there.

But the family has grown in the years since, which has meant more dishwashing, showers and toilet flushes — too much for Sementilli’s septic system to handle.

First the toilets started flushing slower. Then sewage started seeping into the yard, right next to the creek that crosses the Sementilli’s property on its way to the Ohio River.

“My first concern was really the health and safety of my family,” she said, “and I don’t want to pollute the creek and the wildlife that’s in there.”

Replacing the septic would cost more than $17,000; money the Sementillis, like most Americans, don’t just have lying around.

But because Sementilli lives in Ohio, a state with dedicated funding to help residents pay to fix failing septic systems, she was able to fix the problem quickly, ending the stream of pollution into the creek.

If she lived in Michigan, which does not have such robust, widely-available supports, Sementilli might have had to let the problem fester, polluting the creek in the process until she could find the cash for a fix. And because Michigan doesn’t have uniform statewide septic regulations and many local health departments take a hands-off approach to septic pollution, there’s a good chance nobody would notice.

Michigan lawmakers on both sides of the aisle hope to change that dynamic by using some of Michigan’s COVID-19 relief dollars to set up a septic repair fund similar to Ohio’s. Some environmental advocates see it as a potential first step toward a renewed push to end Michigan’s reign as the only state in the nation without a statewide sanitary code.

A model for Michigan?

Since 2016, the Ohio annual grant and loan program that made Sementilli’s septic fix possible has paid to repair or replace more than 3,600 systems, and help hundreds of additional people with problem septics connect to nearby sewers instead.

Like Michigan, the buckeye state is plagued by pollution from hundreds of thousands of leaking septic systems that treat household sewage. A 2012 survey by the Ohio Department of Health found that 31 percent of the state’s septic system, or 194,000, are failing.

On the heels of that report, Ohio updated the state’s sanitary code in 2015, making changes that require septic owners across the state to periodically prove their system is still functioning correctly.

Past attempts to update the code had failed in part because lawmakers saw it as placing an unfunded mandate on residents: Septic systems are common in rural parts of the state, which also tend to skew lower-income. Some lawmakers worried new regulations would harm people who can’t afford to fork out thousands of dollars to fix a failing septic sewage system.

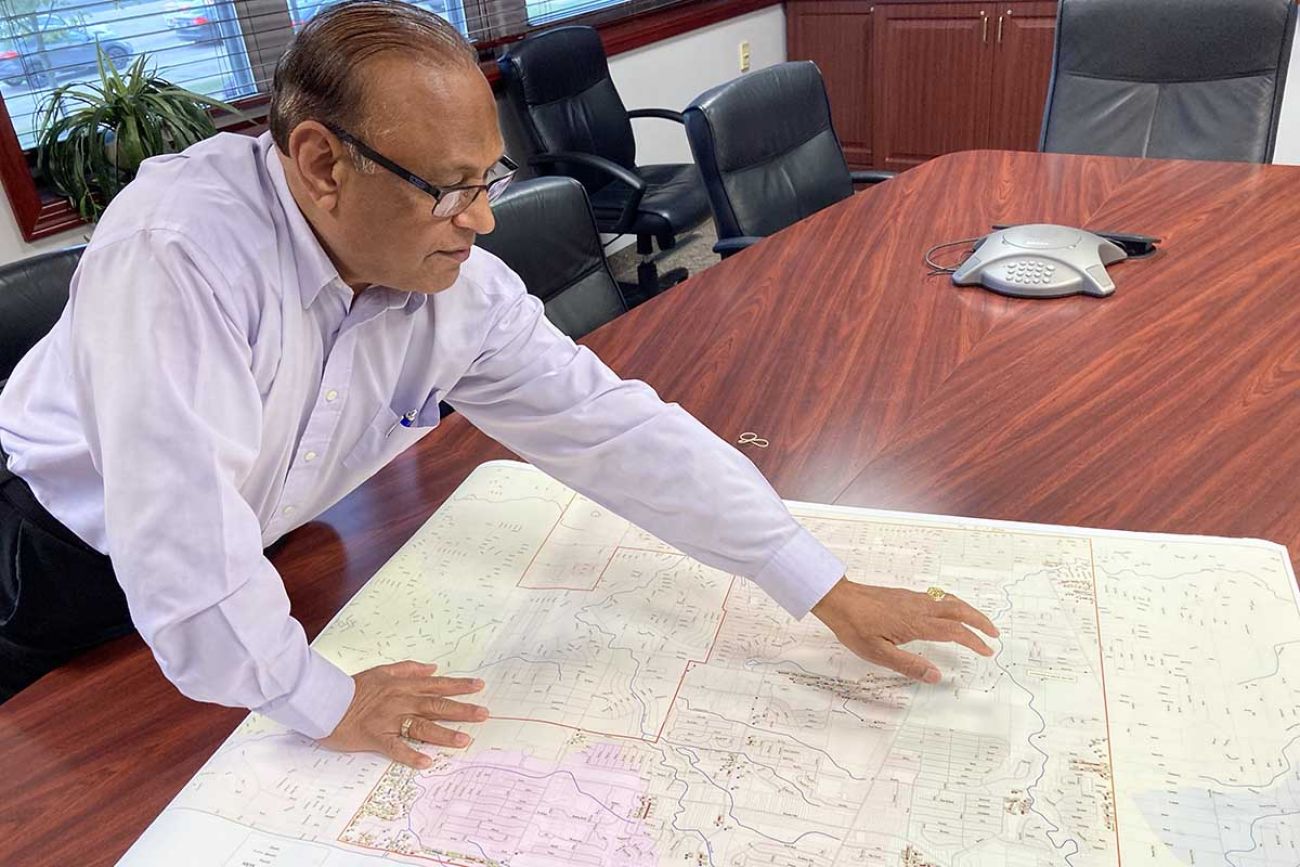

Parma City Engineer Hasmukh Patel points out parts of the Ohio city where residents still use septics to treat household waste. The city is in the process of eliminating septic systems, hooking neighborhoods up to the city’s sanitary sewer system in hopes of alleviating bacteria issues in local waterways. (Bridge photo by Kelly House)

Having funding available to septic system owners through the state’s Water Pollution Control Loan Fund, said Rebecca Fugitt of the Ohio Department of Health, was “a key component” that helped create buy-in for a new code.

Since 2011, the Ohio EPA has used that fund and others to award $82.6 million to help people repair and replace home sewage systems. Homeowners must be of low- or moderate-income to access the funds through their local health department, covering all or part of the project cost depending on the applicant’s income.

Athens County Environmental Health Director Patrick McGarry said the state funds help local governments in the high-poverty region fix looming public health hazards without creating financial crises for individual homeowners.

Common in rural areas without municipal water treatment systems, septics are private systems that typically capture sewage in an underground tank, where solids settle to the bottom and liquids slowly disperse into the soil. They can last anywhere from 15 to 40 years with proper maintenance, including periodically hiring someone to inspect the tank and pump waste out of it.

But many septics in Michigan have exceeded their lifespan without being replaced, causing them to pollute nearby waterways.

Failing septics can send raw sewage into the environment, where it can make people sick by spreading bacteria such as E. coli, viruses and algae-feeding nutrients. Even working septics can sometimes harm the environment and human health when packed too densely in a given area, experts have found.

But without assistance for low-income septic owners, McGarry said, “when you have homes and property that are worth less than the sewage system is going to cost to put in, it just doesn’t happen.”

Ultimately, he said, the Ohio funding program saves public dollars. By footing the bill for septic replacement, he said, taxpayers save on costs tied to water pollution, from healthcare bills to cleanup efforts and lost recreational opportunities when waterways become so polluted, they’re unswimmable and unfishable.

It’s too early to tell whether the program is having a measurable impact on water quality across the state, said Fugitt of the Ohio Department of Health. The department this year will begin a process to survey local health departments to understand whether septic failure rates declined since the new regulations took effect.

The goal, Fugitt said, is to get that down as close to zero percent as possible.

On a local level, McGarry said, it’s clear the program is working. Raccoon Creek, near Sementilli’s home, was once plagued by pollution from septics and mining. Now, he said, it’s water quality is among the state’s best.

In Michigan, spotty oversight, polluted lakes

Michigan’s efforts to better-regulate septic pollution have followed a similar pattern.

Lawmakers have repeatedly attempted to create statewide standards for how Michigan’s septic systems are designed, built and maintained, only for the efforts to disintegrate amid complaints that new regulations would burden the poorest homeowners with hefty repair bills, overtax local health departments, make it harder to sell houses and unduly intrude on private property.

But as a consequence of failing to fix failing septics, pollution is getting worse in Michigan’s waterways, said Joan Rose, a Michigan State University microbiologist who has studied the problem.

Rose led a team of Michigan State University researchers who tested 64 Michigan waterways, discovering that those with the most nearby septics had the highest levels of human fecal bacteria.

Michigan has roughly 1.4 million septic systems, and Molly Rippke, an aquatic biology specialist with the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy, estimated as much as 20 percent of them could be failing.

About half of Michigan’s rivers are harboring too much E. coli to safely swim in them, Rippke said. That pollution comes from a variety of sources, including septics.

“But of course, all rivers lead to lakes, and also to the Great Lakes where our favorite beaches are,” Rippke said.

And harmful algae blooms, which thrive in water bodies that are packed with nutrient pollution from septic systems, lawn fertilizers and farm runoff, are also a growing problem across the state.

The new Michigan spending proposals from both Republican and Democratic lawmakers, both of which build upon an earlier proposal by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, call for spending tens of millions of dollars to fix septics.

They’re among several priorities for how Michigan should spend billions in federal stimulus funds that weren’t allocated when lawmakers passed a state budget last month. The Republican proposal would make $35 million available for failing septics, while the Democratic proposal would dedicate $100 million to the issue.

Either of those sums would make a significant dent in Michigan’s septic pollution problem. But unless the funds continue year-over-year and are paired with regulatory changes, they are unlikely to solve it.

The 21st Century Infrastructure Commission, a group appointed by then-Gov. Rick Snyder, concluded Michigan needs both regulatory changes that require homeowners fix their septics, and about $20 million annually to help people with “demonstrated financial need” get the job done.

Septic owners who can afford to fix their system themselves should be expected to do so, commissioners said.

In the absence of statewide standards, local communities are largely left to decide for themselves when and whether to regulate septics. Often, local officials don’t even keep tabs on where all the septics are, let alone which ones are failing.

“The local codes vary a lot, and that can be an issue,” Rippke said.

Funding to fix septics could be key to making future conversations about septic regulation more palatable in Michigan, said Dendra Best, executive director of the nonprofit Wastewater Education.

“You need one in place before you can do the other,” Best said.

Health departments across the state must permit and inspect newly-constructed septic systems. But once that’s done, there is often little to no follow-up in the ensuing decades to make sure the system continues working properly.

Health departments in 10 counties around the state go further, requiring a septic inspection before a property is sold. What they’ve found has been cause for concern: In Ingham County, 13 percent of septics weren’t working properly. In Macomb, it was 15 percent. In Barry and Eaton Counties, whose point-of-sale inspection program has since been rescinded, 27 percent.

But in the rest of the state, where such periodic inspections don’t happen, health officials have little idea how many polluting septics are out there.

As a result, some local communities are left to contend with worsening water quality problems due to failures or simply too many septics in a confined area, sometimes leading to fights over how to fix them.

Townships around Higgins Lake, for example, are trying again to get area homes off septics and onto a public sewer system after past attempts fell through in part because of concerns about the high up-front costs to install sewers.

Residents near Higgins Lake in Roscommon County have long debated how to address septic pollution in the lake. After a past failed attempt to transition area residents onto a sanitary sewer system, local officials are trying again. (Shutterstock)

Nutrient pollution from lawn fertilizer and septic systems is choking Higgins Lake, turning its crystal-clear waters green with algae. The problem has only gotten worse in recent years as small cottages were replaced with large homes that generate more sewage, said Greg Semack, vice president of the Higgins Lake Property Owners Association.

“A lot of the houses that were on the lake and in the area years ago were different houses than they are today,” he said. “They were houses that were used maybe seasonally, by a couple people. And they’ve been … replaced by four bedroom houses with washers and dryers and dishwashers and three bathrooms.”

Similar problems along densely-developed Elk Lake, east of Grand Traverse Bay, have sparked a citizen petition drive to get local officials to study the concept of installing public sewers.

“The integrity of the lake, the clarity of the lake, is being threatened,” said Robin Sims, a lakeside property owner who’s spearheading the campaign.

Michigan’s proposed funding programs would also help communities like the townships surrounding Higgins and Elk lakes pay for sewer connections to eliminate septics altogether.

Rose, the MSU researcher, called the proposed funds “a step in the right direction” toward eliminating the bacteria and algae problems that increasingly plague Michigan’s waterways.

But absent a statewide requirement for health officials to keep tabs on septics and force fixes to those that are polluting waterways, Rose said, “we’re just going to kick (problems) down the road, waiting for it to turn into a crisis somewhere.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

2 Comments

-

Great work by Hasmukh Patel. Amazing model for Michigan. It’s great to know that the funding program will save public dollars. Keep it up!

-

Here in Lake County Illinois, a property with a septic system needs to have the system inspected when its sold. Requirements for septic system evaluations are, generally, requirements of mortgage lenders or the real estate industry. There are no statutory requirement for routine evaluations, no established protocol for inspections, and no particular licensure specified.