I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

Any year that includes the opportunity to hold a baby sturgeon in my hand is a good year. This season was particularly special as it was bookmarked with lake sturgeon releases. And while every sturgeon release is special, these two were particularly apropos as the fish went into Michigan’s Sturgeon River.

I had the privilege of joining Kris Dey this spring to release 16 sturgeon.

In 2013, the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians wanted to increase youth awareness and participation in their lake sturgeon, or nmé, restoration program. The Tribe’s education department decided to model an outreach program after the Michigan Department of Natural Resources’ Salmon in the Classroom program. But instead of raising salmon, the students would get to raise a lake sturgeon.

Lake sturgeon are listed as a threatened species in Michigan. Anyone working with sturgeon in any capacity has to operate under a permit which includes a strict set of state and federal regulations. Thankfully, the LTBB hatchery was already permitted to raise lake sturgeon, and this enabled them to provide fish to a classroom. Dey, the hatchery manager, played the role of technical advisor.

The LTBB hatchery is located in Pellston, Michigan, about 30 miles northeast of popular tourist destinations Petosky and Harbor Springs. The high number of tribal residents living in the area is reflected in the Pellston Middle and High School student body. Close proximity to the hatchery and Dey solidified Pellston High as the perfect school to launch the new nmé program.

Lesson plans were developed. A 55-gallon tank and assorted accoutrements were purchased by the LTBB education department and delivered to Brooke Groff’s classroom. The first nmé entered Pellston High School in September 2014.

Survival rates for lake sturgeon in their early life cycle are brutally low in the wild. Hatchery survival rates are drastically higher, but the harsh truth is that many still die. And while fish dying is an accepted reality in fisheries management, it’s a harder lesson to learn when the fish has a name.

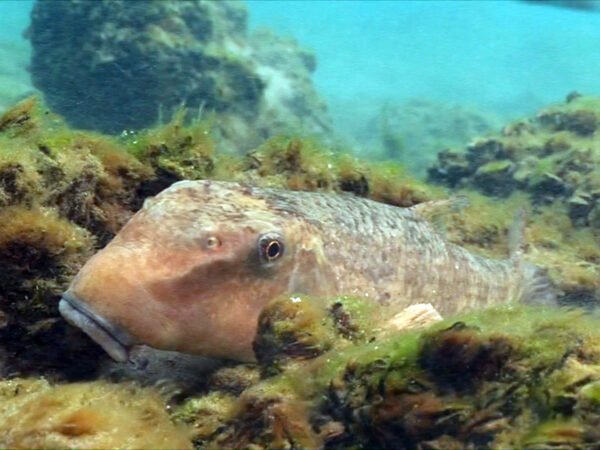

Sturgeon release (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Of course, the goal is for all the fish to survive, and thankfully most do. But in the event of a loss, Dey keeps a special group of replacement fish on standby at the hatchery.

For every fish that goes to a classroom, Dey keeps one to two understudies at the hatchery. If all goes well, the extra fish will never be needed. They will spend the entire school year at the hatchery swimming endless laps around a circular tank.

Each spring, after all the classroom fish have been released by students, the extra fish are loaded into a tank on the LTBB hatchery truck. The nmé are driven 30 miles to a park on the upper stretches of the Sturgeon River. Without any fanfare or singing and just a small blessing with tobacco, the extra classroom nmé are set free.

When it came time to release the 2021 class, I quietly whispered my appreciation for their contribution to the classroom program and thanked each of them for being on standby for the students.

They were beautiful fish, easily 10 times larger than at the start of the school year. Every sturgeon I’ve released in the past I could cradle in the palm of one hand. These fish required two hands to hold.

And they were feisty.

Usually, newly released fish hang around for a few minutes as if to get their bearings. But as we released each of them, they immediately disappeared into the Sturgeon River as if they’d always lived there.

It was unbelievably rewarding to release nmé into the Sturgeon River and an inspiring start to our season.

By September of each year, all the sturgeon that hatched in the spring are large enough and their body armor developed enough that they can be safely released into the wild with confidence that most predators will not try to eat them.

Release events typically take place sometime in September. COVID-19 restrictions continued to affect this year’s events, but I was fortunate to attend the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians nmé release in the Manistee National Forest.

Sturgeon release (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

The LRBOI nmé restoration program operates on a smaller scale than the LTBB hatchery. The LRBOI nmé are reared in shallow tubs in a building that sits just a few hundred yards from the Big Manistee River.

On release days, the tribe opens their facility to the public and encourages people to come play with the nmé. With the staffs’ supervision, of course.

I was surprised by how many people seemed hesitant to touch the little fish. You never have to give me permission twice. I’m the type who is eagerly waiting to plunge my hand into the water the second I get the chance.

But the LRBOI staff really had to coax the first few visitors to reach in and touch the nmé. I don’t think it was a fear factor. Rather, I think we’re all a bit conditioned by the more common societal rule of ‘no touching allowed’.

There was a lot of hesitation.

But once the touching began, the crowd could be heard exclaiming various versions of “That’s not what I expected!”

Lake sturgeon are scaleless, but unlike catfish they are not slippery or in any way slimy. Their skin reminds me more of tanned buckskin tightly stretched over sharp, boney plates. Those sharp plates are called scutes, and they help protect the young fish from predators.

While the LRBOI pipe carrier offered a traditional blessing, the hatchery staff distributed 300 nmé into 150 aluminum 1-gallon pails.

When the ceremony was complete, everyone in attendance was given a pail of fish. I loved seeing toddlers, teenagers and adults of all ages including grandmas and grandpas walking towards the river all carrying little silver buckets filled with nmé.

Each release is personal.

Some people simply pour the fish out of the pail into the river. Some immerse the bucket and let the fish find their way out.

Other do hand releases, often talking to the little nmé before letting them go.

A little boy was startled by the feel of the fish in his hand and unceremoniously toss the nmé about 3 feet out into the river.

A pair of women in their fifties walked barefoot into knee-deep water and blessed each nmé they released with 100 years of prosperity.

I always release mine by hand, usually while kneeling in shallow water.

The atmosphere at the LRBOI release events is always festival, joyful, optimistic. It feels good to give back even if we only get to participate in one tiny moment of the fishes’ journey. But for the professionals who work with fish daily, release days have a different vibe.

The LTBB hatchery released almost 2,000 lake sturgeon this year over about a three-week period. Although the sturgeon enter the hatchery at the same size, some grow faster and each fish needs to reach 10 grams before it can get its tracking marker. The tiny puncture wound caused by the tagging procedure takes around 10 days to heal. When the wound heals, the fish are ready for release.

This year, the LTBB’s first release date was open to the public, but COVID-19 restrictions meant there would be no ceremony or social gathering. A forecast for all-day rain showers proved accurate.

Not surprisingly, only a couple of seasonal staff members were waiting beside the Sturgeon River when the hatchery truck filled with the first 200 nmé to be released pulled into the access site.

A temporary lull in the rain showers had the hatchery staff moving with particular efficiency.

Tobacco offerings were made, but these nmé got no ceremony, no drum, no sweet whisperings from children or blessings from elders. The atmosphere was still optimistic and positive but with a far more practical feel. These were fisheries professionals. Their job was to get the nmé into the river with the least amount of stress for the fish as possible.

Only after all the fish were released did the staff stop to appreciate the moment. I could tell it was poignant for all of them. They’d dedicated the last three months to caring for these fish. They fed them. Cleaned up after them. Worried about their well-being.

In this case, the release-day joy came not from a personal moment of interaction but rather from seeing hundreds of little nmé scattered across the bottom of the Sturgeon River and knowing that many would outlive all of us. The small group of researchers stood in the drizzling rain beside the river until every single little nmé swam away.

Talk quickly turned to next week’s release. But as we walked away from the river, I caught a tiny twinkle of well-earned pride in a couple of their eyes.

Like every other sturgeon release event I’ve attended, I drove home feeling better about life and the future.

There is something about holding a nmé in my hand, even for that brief moment before it swims away, that moves my heart, and I highly recommend it.

Catch more from Kathy Johnson on Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: No petting for these cats

I Speak for the Fish: Shell middens reveal interesting clues about the humble muskrat

Sturgeon release (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)