I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I’m a sucker for a whiskered face. I currently share my home with two domestic felines, so it’s not surprising that I also adore catfish. From uber-chill channel cats to the elusive northern madtoms, catfishes are all around cool. And of the 46 species of catfishes found in North America, you can find only nine of them in the Great Lakes.

In the little creek near our house, brown bullhead catfish form large schools on the surface of the water in the springtime. The newly hatched bullheads look more black than brown. The school of tiny fish forms cool patterns on the surface as they continuously swirl around trying to avoid being eaten by water snakes, turtles and larger fish.

At the other end of the scale from little bullhead hatchlings are the big grey channel cats. These big catfish never seem to be in a hurry to get anywhere. Like many catfish, channels are nocturnal and we often find them hang out in the dark shadows of shipwrecks during the day. Their whiskered faces peeking out of the darkness are so cute I’m always tempted to reach out and scratch their heads. The few times I’ve tried they’re gone before my hand even gets close.

The temptation is strong. All North American catfish are scaleless, giving them a soft, velvety feel. Despite their soft-looking appearance however, anglers or anyone holding a catfish should take care as their dorsal and pectoral fins can inflict painful wounds. The illustrations of the different catfish pectoral fins in one of our field guides resembles a cache of weapons from a post-apocalyptic horror movie.

Having that defensive armor helps to protect catfish from being eaten by predators, but when the table is turned and it’s time to sniff out dinner, no other fish does it better.

Channel catfish (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

A catfish’s barbels which remind us of a feline’s whiskers actually have more in common with a cat’s tongue than their facial hair. Burbot, carp, catfish and sturgeon all use barbels to detect food on the bottom. Each catfish barbel has a remarkable 25 taste buds per square millimeter and catfish have eight barbels around their mouths.

In addition to the barbels, catfish have sensory glands across their entire bodies earning them the moniker of swimming tongues. A tiny six-inch northern madtom could have half a million taste buds covering its body. Catfish have a better sense of smell than any other fish including sharks.

A catfish can detect one molecule per 10 billion parts of water.

Years ago, I heard an interesting analogy for a catfish’s ability to taste. Theoretically, if you poured a bucket of blood into the Straits of Mackinac, a catfish at the bottom of Lake Huron could taste it. Of course, this would never work in the actual lake. Rather, it was intended as an illustration of scale.

Put another way, a catfish can essentially detect a lilliputian drop of aroma in a goliath-sized bucket.

Most catfish are bottom feeders. They are considered opportunistic feeders because they eat just about anything they find from tiny aquatic insects like scuds or shrimp to small crayfish and juvenile fish.

Northern madtom (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

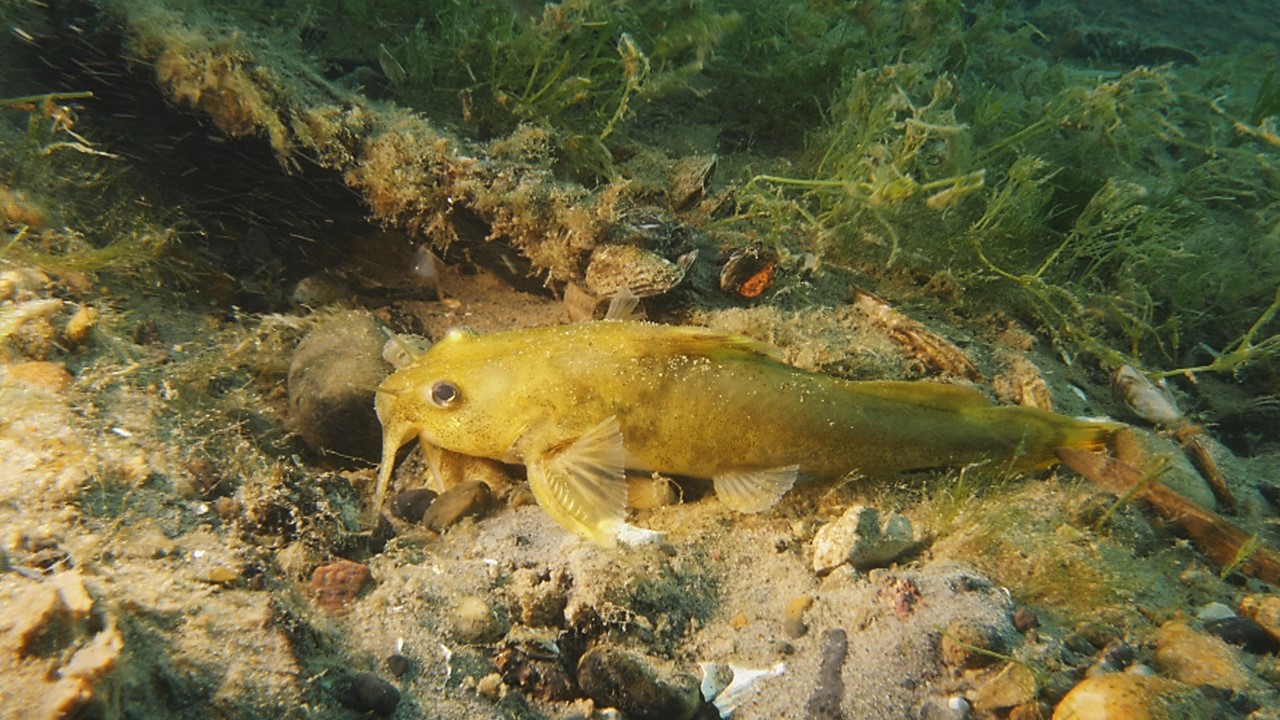

One of my favorite types of catfish is the madtom. They are small, reaching only about 6 inches in length when full grown. The northern madtom we see in the lower St. Clair River are a rich golden color. Their bodies shimmer and glow under our dive lights.

If it wasn’t for some old bottles, we might never have found those madtoms.

A few years back, Greg decided to film a group of divers that liked to dig for old bottles in the lower St. Clair River near Algonac. Treasure hunting is a popular pastime for many divers. We almost never get stock footage requests for divers since our specialty is freshwater fish. But we both agreed that having a little footage of divers hunting for treasure couldn’t hurt.

Greg came home that day without shooting a single frame of with a diver, but he did come home with some golden footage.

One of Greg’s underwater superpowers is an uncanny ability to find and identify aquatic life. He can spot a single 3-inch-long stickleback in a school of a hundred 3-inch-long minnows while they all undulate along the seawall in a three-knot current.

On this dive, he spotted the northern madtom under a log near the dig site and spent the remainder of his dive filming the little golden catfish.

We returned to film the madtoms on multiple occasions to document more behaviors.

Catfish are nest guarders. In the case of northern madtom, the male watches over the eggs and hatchlings. The male shelters them from crayfish, gobies or anything looking for an easy meal. An ideal nest site has no front or side entrances and an easily guarded back door.

Northern madtom eggs (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

A northern madtom’s bright orange eggs form a ball the size of a small marble. When the eggs hatch, the translucent babies cluster together forming slightly larger swirling balls that are annoyingly difficult to bring into sharp focus. Within days, the tiny hatchlings fan out and scatter on the bottom of the nest. When they start to wander off, they are on their own.

About a year after filming our first northern madtom, we got a call from Mary Burridge at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. Burridge is a co-author to the ROM Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario and she had heard we might have footage of northern madtom. If she could get some images, their publisher had agreed to do a reprinting of the book just for the little golden catfish. We were happy to oblige.

Bullhead catfish (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

When we got our revised copies, we were surprised to learn that northern madtom are considered “one of the rarest fishes in Ontario.”

The northern madtoms really are little pieces of gold.

From hypnotic schools of swirling bullhead to chilling channel cats and nesting madtoms, I’m as crazy for cats underwater as the ones sleeping in my living room.

Catch more from Kathy Johnson on Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Shell middens reveal interesting clues about the humble muskrat

I Speak for the Fish: Mussel memory, the race to save an endangered species

I Speak for the Fish: April showers bring vernal pools and baby salamanders

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.

Featured image: Northern madtom (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)