By Kelly House, Bridge Michigan

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan; Circle of Blue; Great Lakes Now at Detroit Public Television; and Michigan Radio, Michigan’s NPR News Leader; who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work HERE.

Six years after Flint stopped drawing its drinking water from the caustic Flint River, Diane Fletcher is still fearful of drinking straight from the tap.

Her property has lost value “because the world knows we have bad water,” she told a federal judge this week. “And I don’t have to speak of the mental anguish.”

But because Fletcher avoided the worst health impacts from the city’s lead-tainted water crisis, the most she can hope to receive from a proposed $641 million legal settlement of civil suits against the state of Michigan and three other entities tied to the crisis is $1,000 for property damage.

In Fletcher’s mind, she and other Flint adults who don’t qualify for substantial payments from the settlement are being “penalized because God blessed us not to get sick or die.”

Meanwhile, lawyers seeking fees that could amount to about 30 percent of the $641 million settlement, she believes, are siphoning off money that “was supposed to be for victims.”

Lawyers who led the effort to secure the partial settlement of lawsuits arising from the crisis, meanwhile, argue they’ve done their best to prioritize those who suffered the gravest harm after a state-appointed emergency manager approved the city’s disastrous 2014 switch from Detroit’s water supply to the Flint River, without requiring anti-corrosion chemicals to prevent lead from leaching out of aging pipes.

As for the fees, the lawyers argued they’re simply seeking fair compensation for more than 182,000 hours of work and $7 millions in expenses they racked up over the years representing residents who sued the state of Michigan and other entities.

Now, it’s up to U.S. District Court Judge Judge Judith Levy to decide who’s right.

Levy on Thursday wrapped up the final day of virtually broadcast hearings designed to give residents and lawyers a chance to argue the merits of the proposed settlement, which she preliminarily approved in January. She is expected to decide later this year whether to grant final approval.

How much should lawyers take?

Stuart Rossman, a director of litigation at the National Consumer Law Center, told Bridge Michigan the proposed fees in the Flint case are not out of the norm.

Class action lawsuits against companies often include lawyer cuts of between 20 and 33 percent, he said. That puts the Flint proposal “on the upper end, but it’s not all that unusual.”

The logic, Rossman said, is that lawyers need an incentive to take on cases that tend to be risky. Unlike lawyers representing individual clients, who often get paid some amount regardless of whether their client wins, lawyers in class-action suits get nothing unless they win.

On Thursday, co-lead attorney Corey Stern defended the proposed fee structure, noting that at least 80 percent of the Flint plaintiffs were not part of a class, but instead signed individual contracts agreeing to give lawyers a certain percentage of their award — typically a third.

Under the proposed fee, he said, his firm has agreed to receive less money than it would have amassed by sticking to those individual contracts (closer to 30 percent than 33 percent).

“There’s no cabal,” Stern said. “This is not a group of people who are, you know, buying yachts together and planning their vacations together.”

But an attorney with the Center for Class Action Fairness at the Hamilton Lincoln Law Institute, which objected to the proposed fee on behalf of Flint residents, argued that logic does not generally apply to mega-awards.

Frank Bednarz, an attorney with the Washington, D.C.-based center, argued that attorney fees in cases with a pot of over $500 million typically average closer to 17 percent, in recognition of the “economy of scale” in such cases.

“The attorneys should get paid,” he told Levy Thursday. “They provided a benefit. But class members should not overpay” for their lawyers’ work.

The closest comparison to the Flint case, Bednarz told Bridge in an interview Wednesday, is the high-profile concussion case against the NFL. In that case, attorneys’ fees were lowered to about 11 percent of the $1 billion settlement after a judge-appointed counsel reviewed lawyers’ higher proposal.

On Thursday, Bednarz urged Judge Levy to take a similar approach. He accused one firm involved in the sprawling litigation of overcharging tenfold for work performed by contract attorneys earning as little as $50 an hour.

Levy said the court already intends to do a “flyspecking” review of lawyers’ reported expenses.

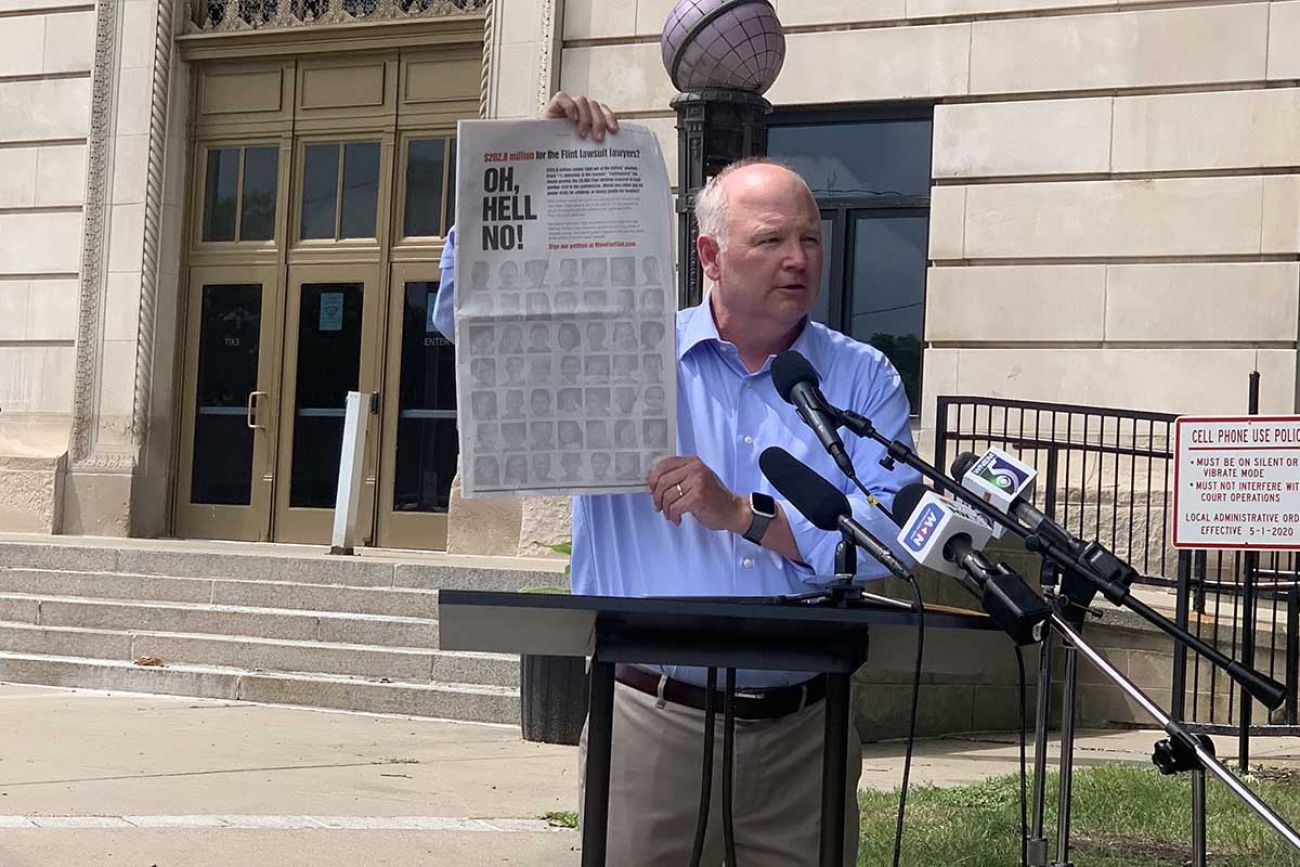

The fee proposal has also received blowback from members of the Michigan House of Representatives, who in March adopted a resolution against it.

State Rep. John Cherry, D-Flint, who co-sponsored the resolution, called the proposed fees “wildly inappropriate,” in an interview with Bridge. He argued lawyers should get closer to 10 percent of the settlement pot.

Levy gave no indication of whether she’ll accept the fee proposal, but noted that “I personally have a very hard decision to make.”

‘No one was untouched’

The proposed settlement, which would resolve only a portion of civil suits tied to the Flint water crisis, includes commitments of $600 million from the state of Michigan, $20 million from the city of Flint, $20 million from McLaren Regional Medical Center and $1.25 million from Flint-based engineering firm Rowe Professional Services Co., for their respective roles in the failure to protect city residents.

More than 50,000 people have registered to participate in the settlement, although it won’t be clear for months how many of them have valid claims. Registrants will have to prove they qualify and submit medical records or other proof that they suffered physical harm or business or property loss.

Payments won’t come until next year at the earliest, and there’s a chance the pot could shrink between now and then. Case Special Master Deborah Greenspan said during Thursday’s hearing that it’s unclear whether McLaren will remain part of the settlement because plaintiffs with claims against the hospital declined to participate in the settlement.

Lawyers continue to pursue lawsuits against four other parties tied to the Flint water crisis, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The current settlement prioritizes children, who will receive some 80 percent of the pot after attorneys fees. Another 2 percent will go toward special education programs in Genesee County, where Flint is located.

That leaves 18 percent for adults who can prove they suffered health impacts or property damage, and 1 percent for business losses.

That breakdown has drawn rebuke from adult residents who say they shouldn’t be left out just because they can’t prove they were poisoned.

“No one was untouched by this,” resident Claire McClinton said in an interview with Bridge. “There’s a lot of emotional consequences to this whole experience that we’ve shared as a community.”

McClinton called the $641 million far too little. She wants to see money for traumatized residents to receive counseling. She wants more compensation for residents who had to repeatedly replace water heaters destroyed by caustic water.

The proposed settlement, she said in remarks to Levy this week, “might be legal, but it’s sure not right.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

‘Some crumbs’: Critics urge rejection of $641M Flint deal

Dispute over Flint bone scan device heats up in water cases