A Wisconsin state park bordering the shoreline of Lake Michigan is teeming with dunes, preserved wetlands and protected plant species. It’s a great view – making it an ideal neighbor for a new golf resort that one of the state’s manufacturing giants has been fighting for years to build.

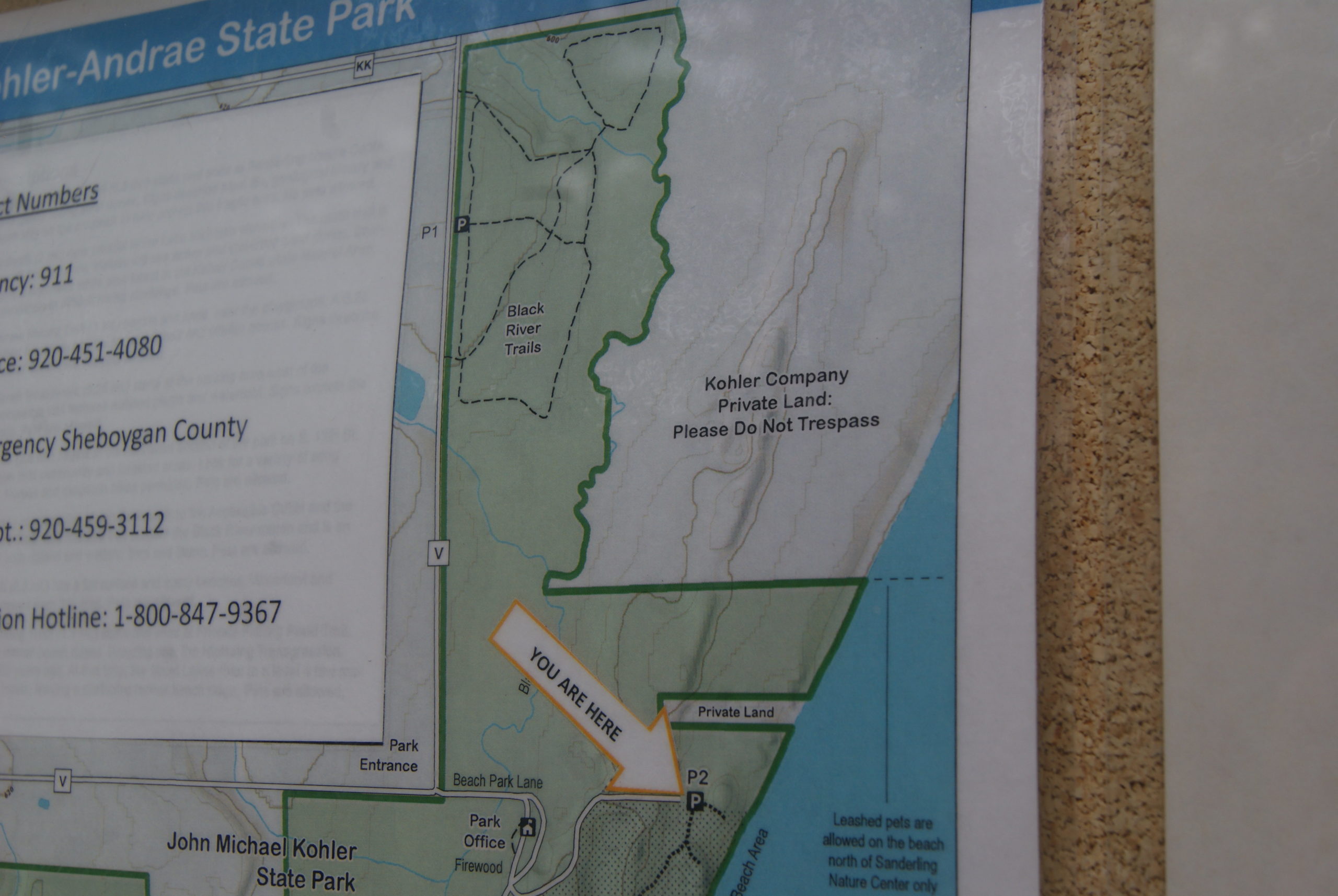

Kohler-Andre State Park is located in Sheboygan County and comprised of two state parks, Terry Andrae State Park and John Michael Kohler State Park. The land totals 988 acres and is managed as a single park. Kohler Co. donated land in memory of the company’s founder, John Michael Kohler, in 1996 to create a state park.

Kohler Company, the Wisconsin kitchen and bath manufacturing titan with 35,000 global employees, introduced plans to develop a neighboring 250 acres into a golf resort overlooking the lake in 2014. Nearby residents and environmental groups have voiced concern over harm to the neighboring ecosystems and chemical runoff from golf course management.

Kohler Co.’s tourism and recreation arm, Destination Kohler, manages four other golf courses in Sheboygan County. The company plans to host the biennial, European and United States Ryder Cup at the end of September at the Whistling Straits golf course. The men’s golf competition is expected to draw crowds of thousands to the area, boosting interest and intrigue for the continued expansion of their resorts in the region.

A map located at Kohler-Andre State Park shows visitors the delineation of public parkland and private Kohler property along Lake Michigan. (Photo Credit: John McCracken)

In late May, a Sheboygan County judge denied a wetland permit Kohler Co. submitted in 2017. The permit to fill a wetland was contested by Friends of the Black River Forest, a local environmental advocacy group. It was appealed by Kohler Co. after being rejected in 2019.

Aside from the wetland permit, the project is waiting on a master plan amendment.

Dirk Willis, vice president of golf, landscape and retail for Kohler Hospitality said Kohler Co. believes the facts and the law show that the wetland permit should have been upheld and the company is currently reviewing options to determine the best plan forward for the project.

“The DNR staff put a lot of scrutiny into our wetland application, including nearly four years of analysis, public meetings, and a detailed and comprehensive environmental impact review of this project,” said Willis.

Mary Faydash, a spokesperson for Friends of Black River Forest, said her advocacy began when she heard of Kohler Co.’s plans to develop land adjacent to a rare part of the Lake Michigan landscape.

“I had vacationed in Wisconsin since I was a child, and moved here part time in 1997, full time (in) 2010. I could not believe how the assaults (on) Wisconsin’s common resources of land, air and water had degraded our state,” said Faydash.

The rare part of Lake Michigan’s landscape Faydash describes are some of Wisconsin’s last remaining sand dunes. Faydash said Kohler Co.’s development threatens the protection of these rare land formations as well as the interdunal wetlands inside of the park system.

“I thought to myself, it’s 2014. The rest of the world is planting trees, and fighting pollution and saving wetlands because of (wetlands’) tremendous ability to mitigate flooding, and this company wants to remove a unique area that can never be replaced,” said Faydash.

Wetland dunes, threatened species and human remains

Apart from the dunes, there are several other unique features inside of Kohler-Andre, including endangered plants.

According to The Natural Resource Foundation of Wisconsin, thickspike, pitcher’s thistle, clustered broomrape, sand reedgrass, dune goldenrod and prairie dunewort all reside inside the park system and are designated as threatened or endangered in Wisconsin.

Opponents of the golf course have raised concern over a May report by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism where it was revealed that human remains—thought to be Indigenous people who lived in the region between 500 B.C. and 1200 A.D.—were found inside of the proposed site. The report also detailed that Kohler Co.’s property is in a region some call “ground zero for burial mounds.”

Willis said the archeology work on the proposed golf site represents an important historical opportunity for public education about those who came before us and our state’s rich history that could have remained unknown.

“During the archeology work, a few fragments of human remains were discovered in different parts of the property not near burial mounds. Upon each discovery, work was temporarily halted and the approved recovery plan was followed. These few human bone fragments have already been reburied after consultation, and in the presence of representatives of Wisconsin’s Native American tribes,” said Willis.

The Black River acts as a natural barrier between public walking trails and the edge of privately-owned Kohler land proposed to be turned into a golf resort. (Photo Credit: John McCracken)

While the construction of the golf course has not begun, Faydash said the development—including the deforestation of 250 acres of trees and filling of wetlands, both of which act as natural filters—will be fatal for Lake Michigan and the surrounding state parks, neighbors and visitors.

“The runoff from agriculture comes into the land, it picks up the pesticides and fertilizers from the golf course and it flows into the shallow sand base-aquifer impacting groundwater, and groundwater is where most of our drinking water comes from,” said Faydash. “What you’re doing is you’re exacerbating runoff into Lake Michigan, which increases toxins into the lake.”

Willis said the proposal is a part of the company’s commitment to create world-class golf courses and their approach has been to avoid, minimize and mitigate potential impacts and to enhance adjacent park facilities.

Kohler Co. is still under litigation—brought forth by Faydash and other members of the Friends of the Black River Forest—for a land-swap that occurred in 2018.

Kohler Co. wanted to use a 5-acre plot of land of state park land to build a maintenance storage facility as a part of its proposed development. The company in turn offered roughly 9 acres to the DNR. The swap was approved by the DNR board in 2018.

Faydash, however, sees the land swap as setting a dangerous precedent for other parks and future dealings.

“(The land) is so ecologically significant and it was left in its natural state for the public to enjoy, for recreation, study and viewing wildlife in their natural habitat. That’s the concern,” said Faydash.

Eroding shoreline meets developed upland

Adam Bechile said Kohler-Andre and its dunes are a unique system in Wisconsin with a sand-rich environment that helps sustain itself.

“Taking the forest and making it into a golf course would definitely be a big change,” said Bechile.

Bechile is a coastal engineering outreach specialist with Wisconsin Sea Grant, a statewide research program dedicated to the stewardship and sustainable use of the Great Lakes and ocean resources.

Bechile said an ongoing major effect to Kohler-Andre and Lake Michigan’s shoreline is the Great Lakes rising water levels.

“We’ve seen highs and lows, and we need to be prepared for all things in between,” said Bechile.

Recent years have had record-smashing water levels around the Great Lakes, but 2020 did not see a break in records.

The aftermath of high tides can be seen along Lake Michigan’s shoreline at Kohler-Andre State Park. Recent years have had record-breaking water levels across the Great Lakes region. (Photo Credit: John McCracken)

High water levels have led to erosion of land formations along the coast, including Kohler-Andre’s dunes and beaches.

“There you had pretty wide beaches, hundreds of feet between the dune and the water line. As the water levels have risen, the beaches gets smaller and smaller,” said Bechile.

While Bechile studies the coastal systems from the perspective of the lakes’ impact, he said development—from smaller residential ones to larger projects—along shorelines can led to increased erosion.

“It comes down to maintaining healthy vegetation on the property, especially near the shoreline. Definitely not clearing out healthy vegetation if you can avoid doing that, keeping those natural buffers in place, making sure you know where water is running off,” said Bechile.

Bechile said erosion is a natural part of the coastal processes, and while humans want to protect investments, they should be aware of the impact they have on shorelines.

“When possible, you want to stay out of the way of nature,” said Bechile.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Challengers to dune development win appeal at top court

Michigan’s climate-ready future: wetland parks, less cement, roomy shores

Great Lakes trails become friendlier for users with disabilities

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: The Kohler Park Dunes State Natural Area is a unique feature of Lake Michigan’s shoreline in Wisconsin. The parkland is directly adjacent to a proposed golf resort development. (Photo Credit: John McCracken)