When biologist Jillian Farkas stepped into the position of piping plover coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in January 2020, there was no way she could have predicted just how unprecedented the coming season would be.

Her role involves coordinating dozens of scientists and volunteers across six states, two tribes and multiple government agencies—all to help preserve the endangered Great Lakes population of piping plovers. In a normal year, this would mean monitoring plover nests and collecting abandoned eggs to be incubated and captive-reared, while also protecting the birds from predators.

Plover chicks spend daylight hours in these lakeside pens for captive plovers at the University of Michigan Biological Station in Pellston, where they learn to forage along the shoreline and experience the shoreline environment. They are also exposed to variable weather conditions like rain and wind that are not found in the captive rearing building. (Photo Credit: Francie Cuthbert)

But last year, Farkas also had to worry about record-high water levels around the Great Lakes (a threat to the birds, because they nest in the sand on the shoreline) as well as a botulism outbreak that killed several newly hatched chicks.

Oh, and a global pandemic that resulted in travel restrictions, which meant reorganizing the captive-rearing program that normally relies on scientists from around the country being stationed at the University of Michigan Pellston Biological Research Station.

“Any given season can have a monkey wrench thrown into it,” Farkas said. “My job is to manage these efforts and have the best response. To do what’s best for the birds.”

An ongoing recovery

Historically, the Great Lakes piping plover population has been as large as 500 to 600 pairs, Farkas said. But in 1986, only 12 to 17 pairs remained. The birds were listed as endangered, and a recovery plan was created to boost their numbers back to 150 pairs, with at least 50 pairs living outside Michigan (since the state hosted the majority of the population). At that point, the birds would be moved down to “threatened.”

Young Piping Plover chicks at Captive Rearing Center. (Photo Credit: Detroit Zoo)

At this point, the breeding pairs have reached a high of 76, which happened before the lake levels started rising. The numbers have fallen slightly since then, but this fluctuation is normal, according to researchers.

It’s no easy task protecting birds whose main form of defense is to fly away—which does nothing to help the eggs. Around the lakes, crows, gulls, opossums, skunks, raccoons and dogs can scare off the birds and feast on their eggs. Property development and human activity also threaten the birds’ nesting grounds on the beach. The strategy has been to track the birds with bands, protect the eggs with wire nest enclosures, and retrieve abandoned eggs or chicks for captive rearing.

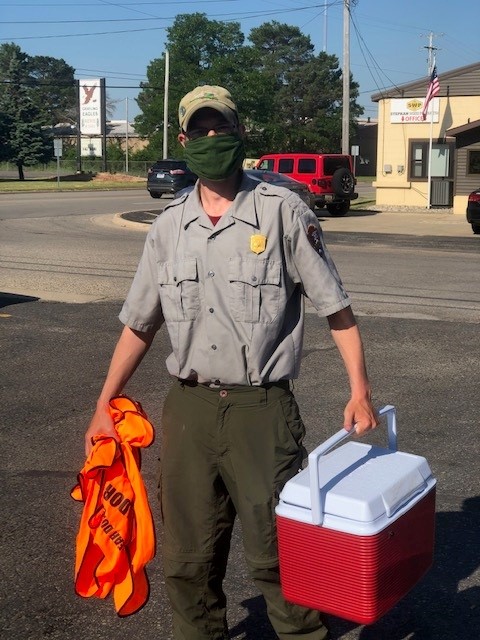

Picking up abandoned eggs from a Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore ranger to transport to the Detroit Zoo where eggs were hatched and chicks raised until stable to transfer to U Michigan Biological Station. (Photo Credit: Francie Cuthbert)

Last year, for instance, 39 chicks were fledged from the captive rearing facility, the highest number ever. That’s largely because so many nests were washed out by high water. The eggs were collected, taken to the Detroit Zoo to be incubated. The chicks were cared for through their first 10 days of life, then transported north to Pellston where outdoor flight pens allowed the new birds to stretch their wings in relative safety.

Thanks to slightly lower lake levels this year, nests haven’t been getting washed out. Only four chicks have hatched in captivity so far in 2021, which means that most plover parents have been able to care for their chicks on their own.

Worth the worry

Francie Cuthbert, a University of Minnesota professor of conservation and biology, has been working with piping plovers for decades. It’s a slow, time-consuming process—but the population has continued to grow, despite all the challenges. To her, the birds are worth all the time and effort because their protection can benefit other species, and because they represent the Great Lakes coast.

Maureen Stine releases a group of captive reared chicks along the Great Lakes shoreline. (Photo Credit: Stephanie Schubel)

This year, 72 pairs have come back to the Great Lakes, and their arrival has brought a few surprises. For the first time in 83 years, a pair built a nest and laid eggs in Ohio, which has been a major cause for celebration. Wildlife monitors in the area are taking a page out of the Monty-and-Rose playbook, since the birds drew so much attention with their arrival in the Chicago area.

A nest in Wilderness State Park, Mich., that hatched the morning of June 23, 2021. Photo taken same day. (Photo Credit: Francie Cuthbert)

Even though most birds don’t achieve the level of celebrity attained by Rose and Monty, Cuthbert says that researchers have almost a personal relationship with the plovers.

“More than 90% of the adults we can recognize as individuals,” Cuthbert said. “We know their histories, we know where they hatch, we know who they nest with.”

Farkas added that the birds’ charisma makes a world of difference in getting the public to support the extensive measures taken to help the plovers recover.

“My background is amphibians and reptiles,” she said. “Most don’t get that following except for sea turtles, and sea turtles don’t count.”

One of the first times Farkas saw a piping plover was in Muskegon, Michigan. The male bird was 10 years old, captive reared and running along the shoreline. He would get hit by a wave and pushed back, ruffle himself, then dart straight back at the wave.

“You are just a little stinker,” Farkas remembers thinking.

Whether the birds are scurrying around, engaged in courtship behaviors or getting territorial with other males—they look like an angry little football, according to Farkas—they’re always fun to see.

“With each state getting more pairs, it’s all very exciting,” said Farkas. “It makes me optimistic for the future.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Piping Plovers: Film fest spotlights endangered bird’s return to Chicago’s Lake Michigan shore

Habitat Focus: To help the birds, nonprofit organization looks to Great Lakes habitats

U.S., Canadian researchers conduct binational birds conservation research

Trump administration rule ends prosecuting industry for unintentionally killing birds

Featured image: Young captive chicks in a lakeside pen where they experience close to natural shoreline habitat. (Photo Credit: Detroit Zoo)