Great Lakes Moment is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

The United States and Canada now have over 40 years of collaborative history in use of an ecosystem approach to protect and restore the Great Lakes.

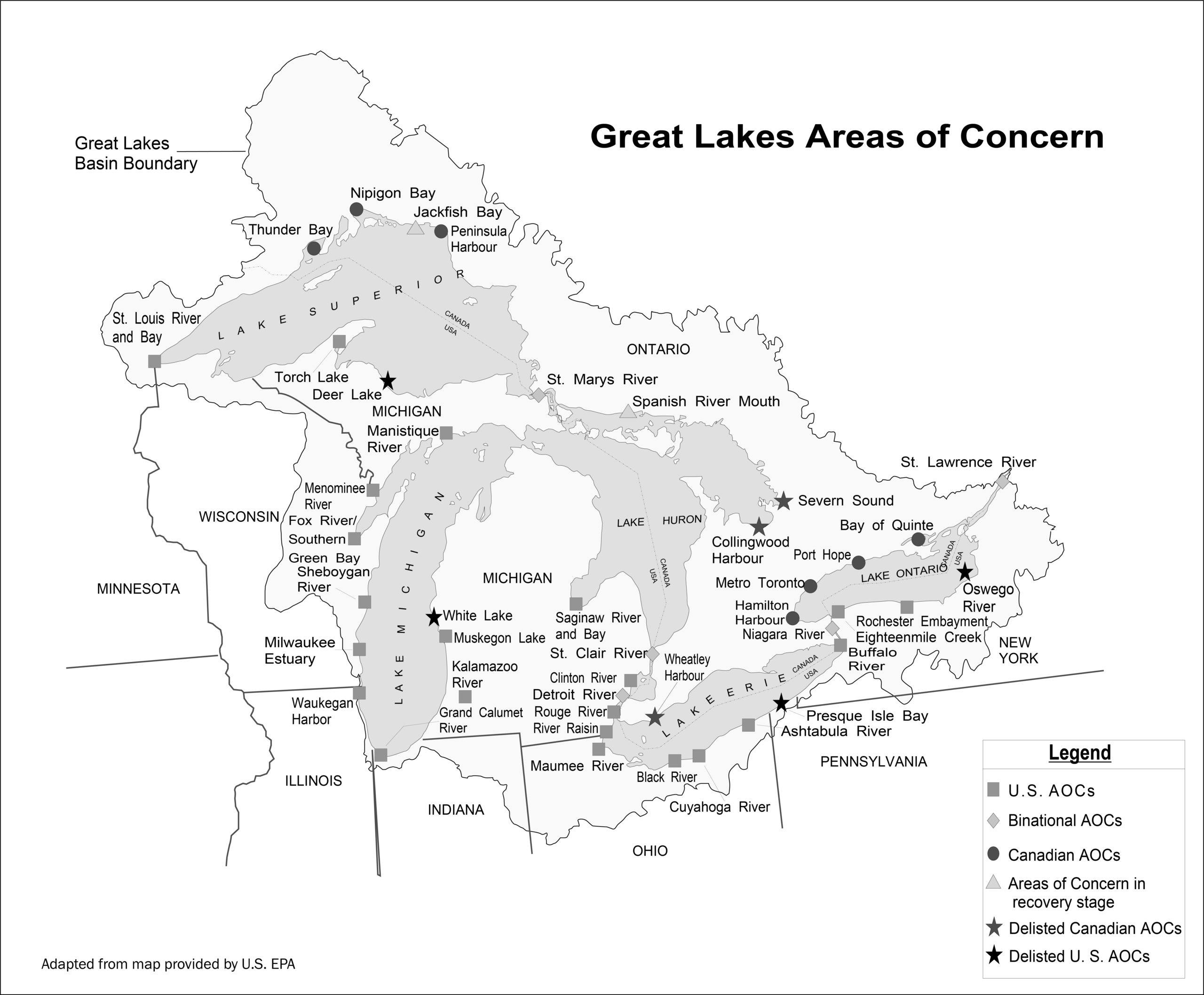

One of the best examples of this is the cleanup of Great Lakes pollution hot spots called Areas of Concern under the Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

A recently published U.S.-Canada study in the journal Sustainability sheds light on how and why institutional arrangements have changed over time to apply an ecosystem approach in restoring AOCs and to address emerging challenges in each local area.

Humans are an integral part of ecosystems

The difference between environment and ecosystem is like the difference between house and home. A house is something that is external and detached – it sits across the street or down the block. In contrast, a home is something we see ourselves in even when not there.

That is why scientists, when describing an ecosystem approach, talk about humans-in-a-system, rather than a system-external-to-humans. What humans do to their ecosystem, they do to themselves.

Ecosystem approach

An ecosystem approach accounts for the inter-relationships among air, water, land and all living things, including humans, and involves all user groups in management.

In 1985, the eight Great Lakes states and Ontario committed to working with the federal governments and local stakeholders to develop remedial action plans to clean up each AOC within their political boundaries and restore impaired beneficial uses.

At the outset, use of an ecosystem approach in action plan development was earth-shaking for state, provincial and federal governments. They were used to implementing water quality programs in a top-down, command-and-control fashion – telling local communities and industries what they had to do. For example, one of the primary programs of state, provincial and federal governments was issuing discharge permits to municipal wastewater treatment plants and industries that prescribed the level of wastewater treatment required and the quality of effluent.

Through use of an ecosystem approach in remedial action plans, all stakeholder groups were charged to work in a collaborative effort.

Think of an ecosystem approach as grassroots ecological democracy for cleaning up polluted areas of the Great Lakes. An ecosystem approach brings all stakeholders who impact or are impacted by a natural resource together to sit around a table and reach agreement on what needs to be done to clean up and care for their ecosystem as their home. Can you imagine the difficulty in bringing factory managers, fishing groups, conservation and hunting clubs, port authorities, sewage treatment plant operators, governments and others together to reach agreement on what needs to be done to clean up their shared waters?

An ecosystem approach is both a way of doing things and a way of thinking. In addition to recognizing an ecosystem as a home, an ecosystem approach acknowledges that everything is connected to everything else, pursues sustainability and works to understand places and integrate processes. Another way of thinking about an ecosystem approach is as a more holistic way of undertaking integrated planning, research and management of specific places like Great Lakes AOCs.

If there was an ecosystem approach to drivers’ training for four students, the driver training car would have four steering wheels to show how all need to work together.

Ecosystem approach (Image Credit: Scott Raft via John Hartig)

Collaboration and partnerships

The above recently published study found that an important part of using an ecosystem approach in cleaning up AOCs is establishing a public advisory committee, stakeholder group or watershed organization broadly representative of the environmental, social and economic interests in each AOC.

Essential characteristics of these remedial action plan institutional structures include broad-based participation to achieve implementation, clear responsibility and authority for both agencies and remedial action plan groups, financial and human support, flexibility and continuity in the process, strong linkages between science and management, and effective education and outreach.

Experience has shown that there was no single best approach to implementing an ecosystem approach in remedial action plan development and implementation.

It is fair to say that there were 43 locally designed ecosystem approaches that helped involve stakeholders in a meaningful way, foster cooperative learning, share decision-making and ensure local ownership.

Structuring the process to create a sense of local ownership of the remedial action plan by participants, who were the very businesses, state and local agencies, and citizens responsible for carrying out the recommendations, was a critical factor in acceptance by all involved.

Essential elements that characterize successful initiatives include true participatory decision making, a clearly articulated and shared vision, and focused and deliberate leadership. Successful AOCs have clearly defined roles and responsibilities for agencies and the local group charged with engaging stakeholders and fostering use of an ecosystem approach, but both working towards the same goal of restoring impaired uses.

This new study also found that institutional arrangements in 35 of the 43 AOCs evolved over time into structures with broader stakeholder representation and more active participation. Broader stakeholder representation and more active participation leads to accessing local knowledge and enhancing creative problem solving. The diversity of institutional arrangements in AOCs led to varying rates of progress in restoring uses. In some cases, cleanup efforts are dominated by governmental regulatory programs that dictate how stakeholders are involved – like hazardous waste site cleanup on the Niagara River in New York or radionuclide waste cleanup in Port Hope, Ontario.

These researchers also found that 32 of the 43 AOCs have established a nonprofit organization or have formed a partnership with Conservation Authorities in Canada that have nonprofit status. The establishment and growth of these nonprofit organizations have helped build local capacity and ownership, broadened the timeline to think about life after being removed from the international AOC list, enabled a watershed focus, and often strengthened the connections among science, policy, and management.

Interagency and public-private partnerships have helped leverage expertise from different agencies and stakeholders while also pooling technical and financial resources. A good example is the Ashtabula River Partnership for the remediation of contaminated sediments in the Ashtabula River AOC in Ohio. In some AOCs, nonprofit organizations were recruited to help revitalize the remedial action plans and lead restoration efforts, like the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper for the Buffalo River AOC in New York. In Hamilton Harbour, Ontario, a unique public-private partnership was used to implement a $139 million (Canadian) contaminated sediment remediation project at Randle Reef – the largest contaminated sediment remediation project in the Canadian portion of the Great Lakes.

This study also found that 30 of the 43 AOCs now recognize “life after delisting” or “sustainability” as part of their focus. For example, the Environmental Network of Collingwood remains active in promoting sustainability 26 years after delisting Collingwood Harbour as an AOC.

In the Muskegon Lake AOC, the Muskegon Lake Watershed Partnership has developed a Muskegon Lake Ecosystem Action Plan to facilitate continued stewardship of Muskegon Lake and Lower Muskegon River Watershed through 2025. It builds upon the restoration progress made under the Muskegon Lake remedial action plan and serves as the community’s guiding document for ecosystem-based management of the watershed and long-term sustainability, while ensuring that Muskegon Lake serves as an economic engine for the local community.

Cleanup of Great Lakes AOCs has been found to be a springboard for local communities to convert areas that were once a detriment to economic growth into valuable waterfront economic assets. For example, cleanup of the Detroit River has led to the development of the Detroit RiverWalk that has reaped over $1 billion of economic benefits in its first ten years.

Finally, use of an ecosystem approach, by nature, is adaptive, where assessments are made, priorities established, and actions taken in an iterative fashion for continual learning and continuous improvement. This is very similar to use of total quality management in the industrial and business sectors. Adaptive management, often called learning by doing, is an iterative learning process for continually improving management policies and practices by learning from the outcomes of previously employed policies and practices.

The future

Use of an ecosystem approach in remedial action plans has required cooperative learning that involves stakeholders working in teams to accomplish a common goal and individual and group accountability – each stakeholder is accountable for the outcome. Experience throughout AOCs has shown that successful plans have fostered use of an ecosystem approach, been cleanup- and prevention-driven, made existing programs and statutes work, cut through bureaucracy, established priorities on a local basis and worked to elevate those priorities within state, provincial, and federal governments, ensured strong community-based planning processes, and been affirming, forward-looking processes.

The next step in furthering use of an ecosystem approach is to take stock of where ecosystem approach originated, where we are now in terms of its application and what must be done in the future to fully realize its benefits.

To accomplish this and promote cooperative learning, a two-day conference titled “The Ecosystem Approach in the 21st Century: Guiding Science and Management” is planned for the fall of 2022 at the University of Windsor in Ontario. This will be convened in celebration of the 50th anniversary of Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

John Hartig is one of the authors of the study discussed in this column.

John Hartig is a board member at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. He serves as the Great Lakes Science-Policy Advisor for the International Association for Great Lakes Research and has written numerous books and publications on the environment and the Great Lakes. Hartig also helped create the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, where he worked as the refuge manager until his retirement.

Catch more on Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes Moment: Walleye frenzy on the Detroit River

Great Lakes Moment: A Great Lakes Way stretching from southern Lake Huron through Western Lake Erie

Great Lakes Moment: Beavers come knocking at the Detroit River’s former Black Lagoon