I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous column here.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous column here.

Our first underwater shoot each spring begins with a long hike through a hardwood forest. Our high-definition underwater camera system and associated gear weigh in at close to 50 pounds, making the 3-mile trek more laborious.

The trees are still slumbering. They won’t begin to bud for another few weeks, but the forest floor is fully embracing spring. Trout lilies, mayapples and stinging nettles cloak the earth in vibrant shades of green from emerald to lime.

We do some light foraging of stinging nettle leaves as we make our way deep into the forest. My husband Greg likes to dry the leaves for a vitamin-rich tea. It’s an acquired taste I have yet to embrace. We keep moving as wild edibles are not why we came.

We’re here for the salamanders.

Each spring, when the ground is still frozen solid and the Easter bunny has yet to appear, melting snow and April showers fill low-lying areas with water, forming shallow pools. These vernal, or spring, pools are short-term wetlands that will be forest-fire dry by the 4th of July.

Vernal pools are a highly valuable wetland habitat that is increasingly threatened across most of North America.

We learned about vernal pools from a friend who is a research biologist. He knew we were interested in all things freshwater and suggested we visit one of his favorite pools. Thankfully, he joined us the first time as we probably would have missed most of the cool stuff otherwise.

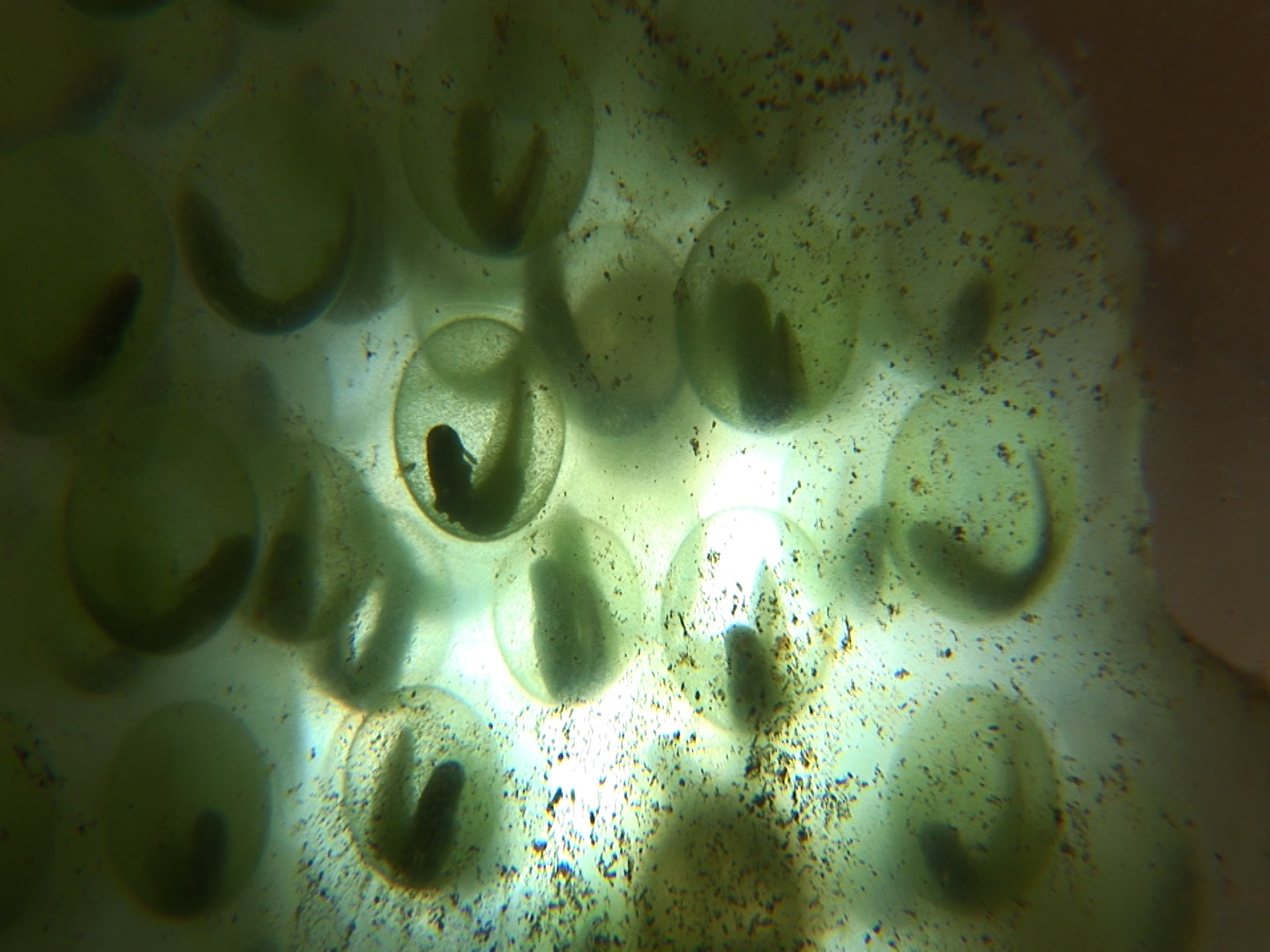

Salamander eggs almost ready to hatch (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

When overnight temperatures are still dropping low enough to freeze the surface of these pools, male and female salamanders emerge from under fallen logs and dense piles of leaves to make their way to the shallow water.

The males arrive first. They enter the near-freezing water at night and deposit their spermatophores along the water’s edge. When finished, the males leave and have nothing more to do with the reproductive process.

Our friend had to point out the spermatophores even though most were only in an inch or two of water. They were just specks of white scattered among the dark brown leaves that form the pool’s floor. Once we learned how to spot them, we couldn’t miss them.

We try to visit our favorite pool before the males arrive and make their deposits. We keep visiting and checking for spermatophores every few days or just once a week depending on the weather. When we see the sperm specks, we know eggs are eminent.

Female salamanders gather the spermatophores into their reproductive opening. About a day later, the eggs will be fertilized and ready. The females enter the frigid water and attach their eggs around the sticks and reeds sticking out of the pool bottom.

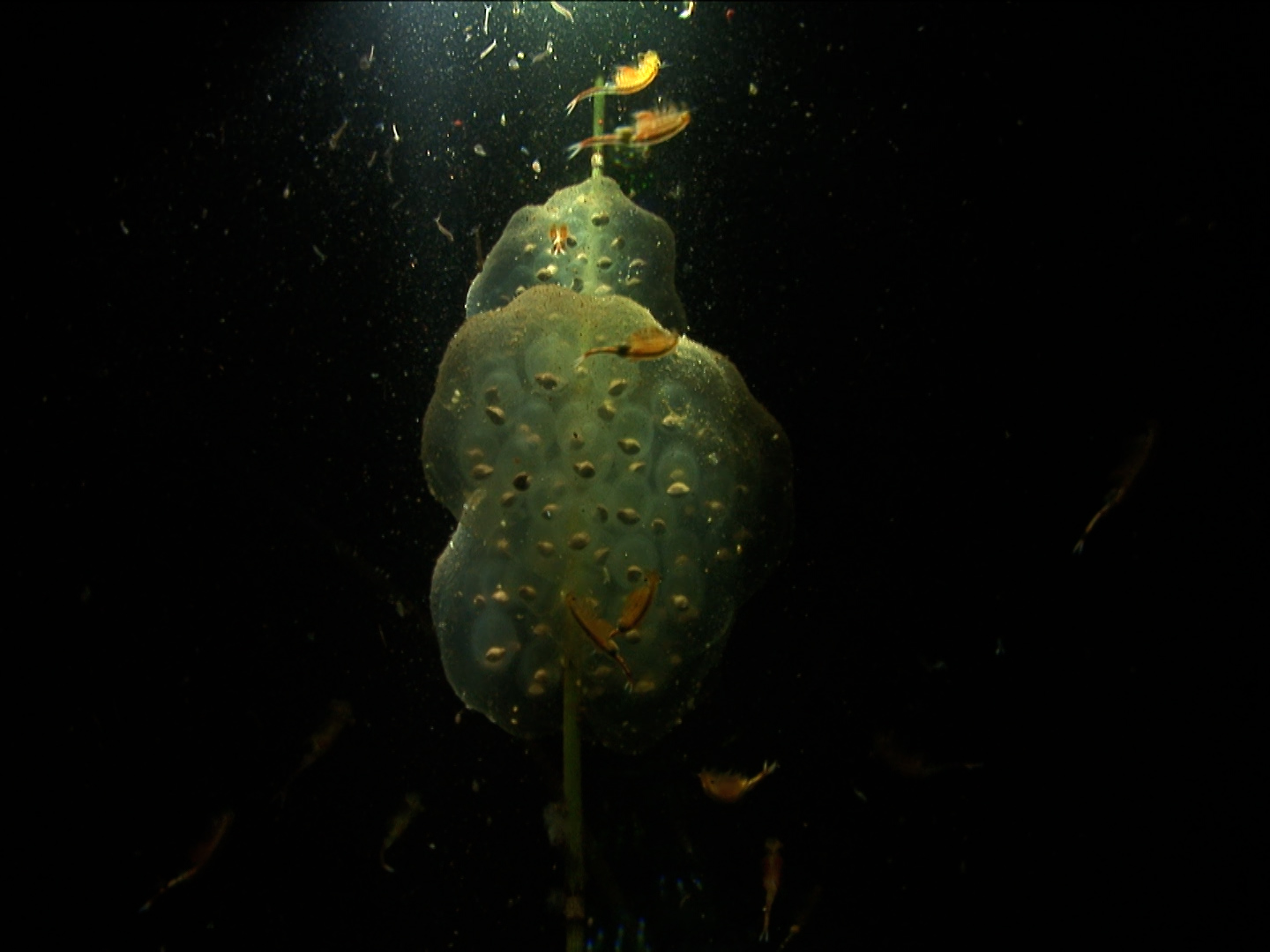

Cluster of salamander eggs in a vernal pool (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

The ideal placement for the eggs seems to be suspended in the water a good 6 inches below the surface to limit access for forest predators like possum and raccoons.

One of the most important features of vernal pools is the absence of fish. Because these areas are only wet for a short time with no outflow to a bigger water supply, fish can’t survive. This lack of swimming egg-eating machines allows salamanders to successfully reproduce, making these pools a critically important habitat.

We spotted the egg clusters without help. They are impossible to miss if one is actually looking. The globs of light-green jelly were speckled with tiny black embryo dots. When the females are done, every stick and vertical piece of debris in the pool is covered with egg globs. Many are lying on the bottom.

The females also head back into the woods, leaving the eggs to survive on their own.

While we don’t technically dive in the pools, filming this process requires Greg to sprawl on the frozen ground in a drysuit with a mask on his face and his hands and arms immersed in ice-cold water while operating the underwater camera.

In a few days, the black embryo dots inside the jelly-like mass morph into the shape of tiny salamanders. The whole egg cluster swells as the embryos grow larger.

Three to four weeks later, depending on the water temperature, the eggs hatch. The larvae have large eyes and clear bodies. They have gills but no back legs. Similar to tadpoles, the little salamanders will gradually develop back legs and their gills will slowly disappear.

As spring turns into summer and the pool begins to evaporate, the young salamanders leave the water and become fully terrestrial juveniles. It will be two to five years before they reach maturity and return to repeat the cycle.

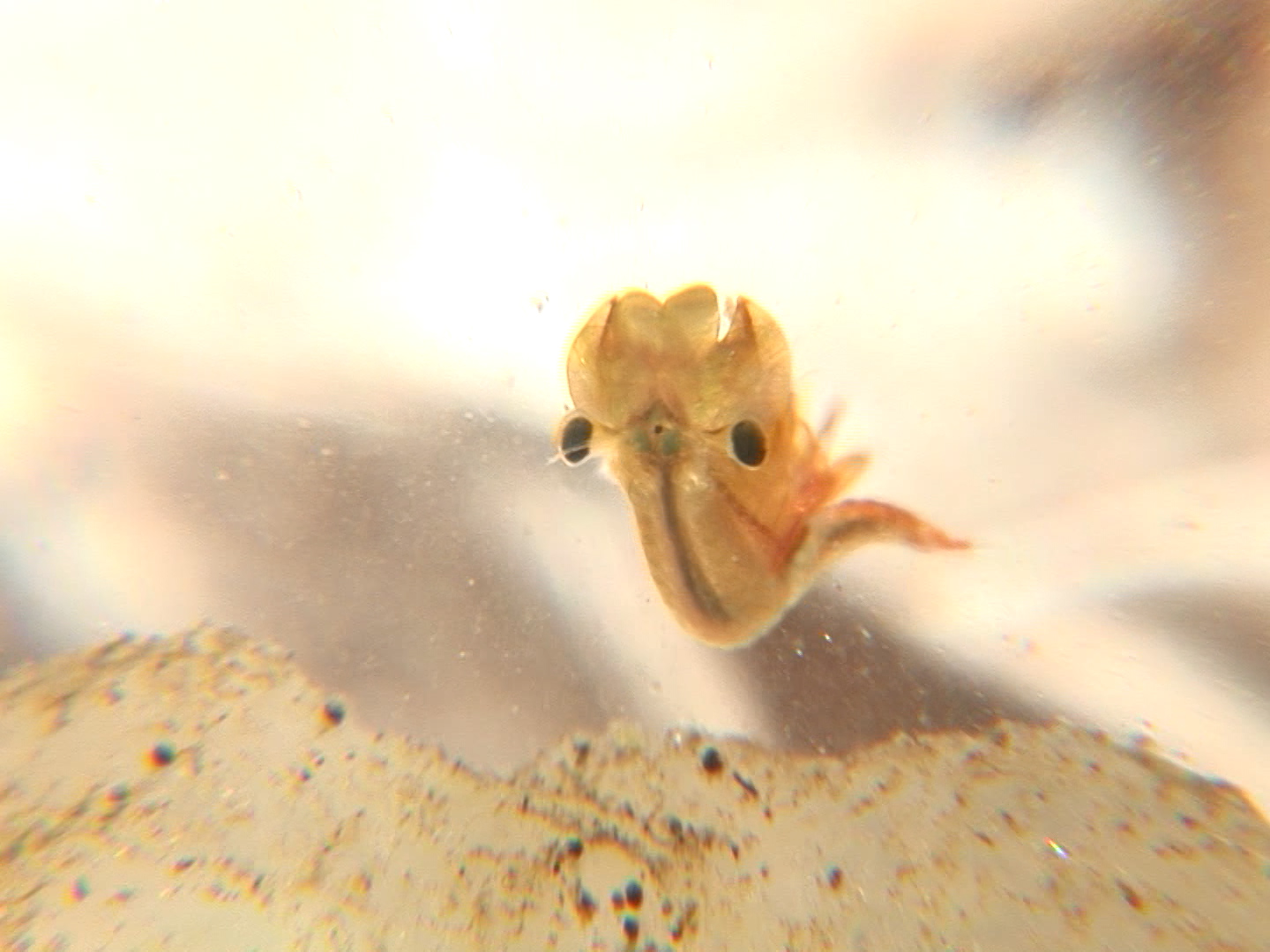

Face to face with a freshwater fairy shrimp (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Salamanders are delicate amphibians which makes them a good indicator of ecosystem health. Lots of salamanders are typically a sign of a healthy system. Chemical pollutants and drought conditions are two of the biggest challenges for salamanders.

Remarkably, salamanders can regrow their tail, limbs and even parts of their brains and hearts. One study even suggests they can recognize shapes and may be capable of counting to three.

In early March, I called our Oscar- and Emmy-winning cameraman-friend Nick Caloyianis for advice on upgrading to a 4K system. When the tech talk was done, I asked what interesting shoots he’d done lately.

Nick, who filmed great white sharks for the Discovery Channel and traveled the world filming underwater for National Geographic, was excited about filming salamanders in vernal pools in Maryland.

We’re excited about our vernal pool shoots in Michigan too. Our new 4k underwater camera system weighs less than 10 pounds, making our long hikes a lot less laborious.

Clearly, professional shooters find freshwater species worthy of their time and effort. Now, if we can just get the broadcasters on board perhaps native freshwater species will finally get the coverage they deserve.

Catch more news and columns from Kathy on Great Lakes Now:

Turtle Recovery: Studying turtles on the Kalamazoo River 10 years after Enbridge oil spill

Turtles vs. Oil: Great Lakes Now producer talks ecosystems, life on the water and covering the lakes

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Fairy shrimp swim around a cluster of salamander eggs (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

2 Comments

-

I loved the article! I have seen similar egg clusters in vernal pools in the past and thought they were frog eggs. Do you know if frogs have a similar process? Thanks!

-

There is an error in this article. Males of most Great Lakes-region salamander species do not just dump spermatophores and leave. They stay in the pools, and vigorously court the females as they arrive, each male trying to steer a female to his spermatophores. Often a swirl of several males will form around a female.