I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

I Speak for the Fish is a new monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

We were enjoying a six-course meal in a five-star hotel in South Korea.

My mother and I along with about 40 other Americans were participating in a U.S. Air Force program that allowed some family members to visit active-duty service members while on overseas tours. In our case, we were here to see my sister, an Air Force captain stationed outside of Seoul.

The Air Force was hosting a welcome dinner for the entire group and our table of 10 represented a broad cross-section of Americans. Between the soup and entrée, a woman across the table who identified herself as being from Salt Lake City, Utah, asked me what I did for a living.

This is an easy question for some people – dentist, fireman, soccer coach. But I’d never had a normal job.

I decided not to mention that I worked as a commercial hard hat diver for years where I spent hours inside the bowels of industrial plants and crawling through sewer pipes. I also skipped over the decade I spent as a search and rescue diver for the sheriff department given neither waste treatment nor body recoveries are ideal topics for dinner conversation.

Kathy Johnson filming in the Thousand Islands area of Lake Ontario (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook)

I considered mentioning my underwater wedding, which took place on a shipwreck in lower Lake Huron. That was usually a crowd-pleaser, but I knew my mother was likely to bring it up, so I skipped that too.

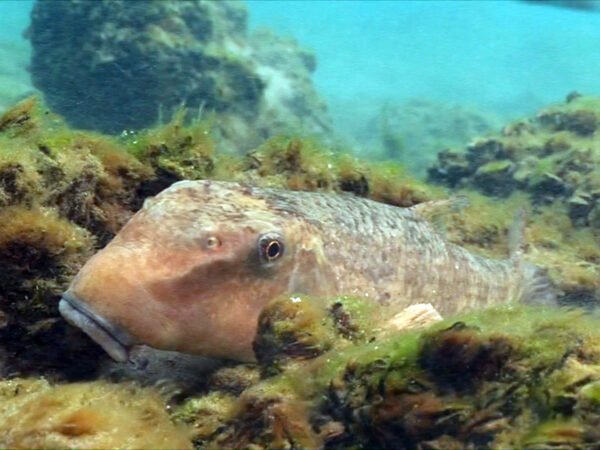

For the last few years, I’d been working as a research diver. I was able to use my commercial diving and dive recovery experience to assist non-diving researchers. The projects varied. We’d saved an endangered mussel population from a dredging project, produced outreach videos, and located important lake sturgeon spawning grounds. I loved the work, but it wasn’t easily summarized and I knew she wasn’t asking for a first edition of my autobiography.

Rather than return her polite inquiry with a huge chunk of information, I simply told her that I was a professional diver.

“So do you teach people how to dive?” she asked.

“No, more like commercial diving,” I said. “Basically, I help researchers study fish.”

“Oh, cool,” she said. “So, where do you live? California? Florida?”

“Michigan,” I said.

“Michigan?” She frowned deeply. “Where do you dive?”

“The Great Lakes.”

“But isn’t that where the dirty water burns, and it’s filled with all kinds of bad things?” she said, and I saw heads around the table nodding in agreement.

Apparently, a good portion of the country hadn’t gotten an update on the Great Lakes in 30 years. Because that’s how long it had been since contaminated pollution floating on the Cuyahoga River, a tributary of Lake Erie, caught fire.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on the Cuyahoga River fire:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.As a diehard Great Lakes advocate, it pains me to realize what a low opinion many of my fellow Americans have of the Great Lakes. Unfortunately, my dinner mates are not alone in their poor perception of the Lakes. I can hardly blame them. If all one hears is bad news, the natural takeaway is that things must be bad.

In 1969, headlines around the globe carried the news that the Great Lakes were “burning.” It lead to billions of dollars invested in clean-up and a slew of legislation aimed at improving the Great Lakes’ water quality, none of which made for sensational headlines.

Sadly, the old newsroom adage that ‘if it bleeds it leads’ still holds water. Media outlets far and wide continue to publish story after story about lamprey eels, zebra mussels and other invasives. Meanwhile, apart from the lake sturgeon, native freshwater species receive almost no coverage.

The solution to this perception issue – and I believe undervaluing the Great Lakes is a major issue – seemed as clear to me as the translucent waters of Lake Superior where a diver can see the surface rippling from 50 feet deep.

If people could see what I’ve seen, I’m certain they’d be amazed by freshwater life just like me.

Unfortunately, life underwater remains outside the realm of most peoples’ personal experiences. This means that the generally held perceptions of the underwater world come primarily from TV and movies.

Consider for a moment the impact Hollywood has had on ocean life.

Jacques Cousteau first brought underwater world into people’s living rooms. His documentary television series inspired generations of young men and women to become certified divers. Cousteau’s filmmaking and passion for marine life is often credited with kick-starting the global marine conservation movement.

In contrast, Peter Benchley’s infamous film Jaws is often criticized for heartening the near-global warfare on sharks. The Discovery Channel Shark Week programming was launched by shark advocates in an effort to change the mass perception that sharks are marine serial-killers. Not surprisingly, programs featuring great white sharks continually receive the highest Nielsen ratings.

Orcas, or killer whales, are an ocean predator with a slightly more successful film image. Two years after the release of Jaws, the motion picture Orca cast killer whales in a similar light as great white sharks only more intelligent and therefore more deadly. Global orca populations suffered, and many were placed in captivity. And then along came Willy and worldwide calls went out to free these beautiful whales.

In 2018, social media platforms exploded with orca advocacy as millions of people followed the heartbreaking story of Tahlequah, a female member of the Southern Resident population, who carried her stillborn calf with her for 17 days.

When it comes to coral reefs, few have had as positive an impact as Disney. The Finding Nemo and Little Mermaid franchises have fostered generations of ocean advocates. Life in the Great Lakes could surely benefit from a little of this Disney magic.

To date, the mass media’s take on freshwater has been more horror-movie scary than Free Willy inspirational.

For those thinking freshwater fish aren’t pretty enough for a leading role, I would submit that if an old sea turtle can be animated to look as adorable as Crush in Finding Nemo, then just imagine what a digital artist could do with a painted turtle or rainbow trout! Who knows, maybe the general perception of how pretty freshwater fish are would change if showcased in Disney color.

But, to play a leading role first you have to get an audition and native freshwater species rarely get the casting call.

Take for example a recent stock footage request I received from a producer in Toronto. Were they interested in schools of emerald shiners? No. How about log perch rolling stones? No. Nesting sunfish? Nope, just some 4k footage of zebra mussels, please.

Watch Kathy’s Great Lakes Now segment on how native species are adapting to Great Lakes invasives:

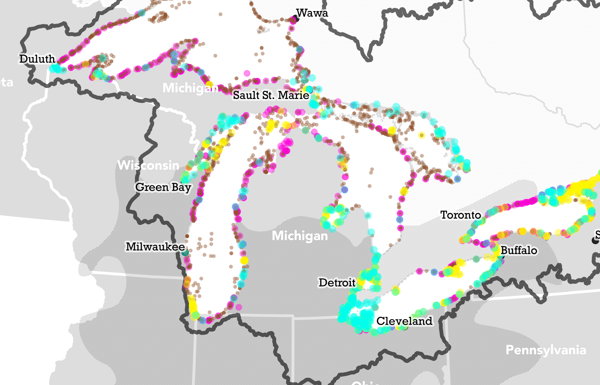

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Since my epiphany in Seoul, I’ve become a champion for all things freshwater. I’ve spoken at club meetings, professional conferences, tradeshows and elementary schools across the Great Lakes basin. I’ve written articles and blog posts, posted videos to social media and last year began producing for Great Lakes Now.

And now when people ask what I do, I say I speak for the fish.

Catch some stories from Kathy Johnson on Great Lakes Now:

Road Salt: Researchers look at vegetables and juices for alternatives to salt

Shipwreck Life: How fish and other aquatic species utilize Great Lakes shipwrecks

Rescuing History: Museum experts across Michigan race to save the Midland archive

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Kathy Johnson with a rainbow trout (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook)

3 Comments

-

Good work Kathy. The Lakes are a treasure that. Need more publicity.

-

Bravo!

-

This is so great. I love freshwater fish too! I’ve been snorkeling on Lake George, in upstate New York, for a couple of summers now, and I can not get enough. I would love to tour the great lakes for a year.