If you have the good fortune to gaze at a Great Lake – any Great Lake – sometime in this strange year, you’re not likely to spot a glaring example of President Joseph R. Biden’s new emphasis on protecting the environment.

But that doesn’t mean they aren’t coming.

Biden’s sweeping actions started almost immediately after he took his seat at the Resolute Desk in January. He signed executive orders meant to restore weakened regulations, take on climate change and address environmental racism – all of which will impact the Great Lakes in some way, sooner or later.

Nick Schroeck, associate professor of law at the University of Detroit Mercy

“A lot of the stuff seems a bit existential,” said Nick Schroeck, an associate professor of law at the University of Detroit Mercy, who has spent much of his career focused on environmental law. “The climate change executive orders are super important, and it’s good to get policies going that will hopefully mitigate climate change and help us avoid the worst outcomes. But it’s a lengthy process that people won’t recognize tomorrow.”

Some – like the Waters of the U.S. law that defines what needs protecting – may take years to litigate, and a lot depends upon political will. Environmentally speaking, Biden is undoing Trump, who undid Obama, et cetera. Recurring policy reversals on long-range issues won’t accomplish much, Schroeck explained.

Still, there are some changes likely to show up across the Great Lakes basin in the shorter term. Among them:

Cleaner air

Some of this is under way: Utilities in most Great Lakes states are phasing out coal in favor of cheaper, cleaner-burning natural gas. And as coal plants close, wind and solar will take up a greater share of the energy burden, especially with federal incentives. All of that adds up to steadily improving air and better public health, especially in neighborhoods where poor people have been forced to live near heavy industry.

“If you close down a coal power plant, you’re going to eliminate hundreds of toxic emissions that have been going up that stack,” said Rhonda Anderson, the Michigan Environmental Justice Coordinator for the Sierra Club in Detroit. “Let’s just talk about one – SO2 (sulfur dioxide). What would that mean? Immediate improvement. You take one from one, that’s zero. At the very least there should be less asthma, less upper respiratory distress, less cardiovascular illness. The effect would be immediate.”

More renewables

Wind turbines across a Great Lakes horizon aren’t coming this summer, but an offshore-wind-powered future is stirring. A Biden executive order calls for the United States to double its offshore wind production by 2030.

It takes a heavy lift to get an offshore wind project up and running. Site plans must find the ideal combination of steady wind, shallow water and proximity to the existing electrical grid.

One such location has been found in Lake Erie about 8 miles offshore from Cleveland. The Icebreaker Wind project has made it through most of the permitting process and is expected to produce about 20 megawatts of electricity for Cleveland by 2022. (By comparison, the Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Plant near Sandusky generates almost 900 mW.)

It’s small, but wind proponents say Icebreaker Wind will set an example for future projects in the Great Lakes. Michigan did a deep dive on offshore wind in the early 2000s under Gov. Jennifer Granholm, but the effort fizzled. Even if those reports are dusted off and the effort revived with federal encouragement, experts advise patience.

“The economics are not there yet for widespread use of offshore wind in the Great Lakes, and probably won’t be for 15-20 years,” said Douglas Jester, an energy consultant with 5 Lakes Energy, based in Lansing, Michigan. “Offshore wind is in competition with solar, onshore wind and other technologies, and right now those are the better options.”

Related stories on Great Lakes Now:

Great Aspirations: Great Lakes states grapple with climate change and carbon

Winds of Change: Wind turbines on Lake Erie spark big support and big debate

Lake Erie Wind Farm Divides Environmental Activists

Power to the people

Rev. Joan Ross

The Rev. Joan Ross has spent the last decade-plus working to get solar power into Detroit’s low-income neighborhoods, where aging housing stock adds real dollars to electric bills that people struggle to pay. Biden’s Justice40 Initiative aims to direct 40% of investments to disadvantaged communities.

“This news is very welcome,” she said. “It will increase solar in our community, which will save money for homeowners, farmers, businesses, and it will create a better environment and better public health outcomes. I’m also excited it will create a lot of jobs and get people back to work on an exciting thing. It’s like futuristic. It’s like tomorrow, it’s advanced. Not the same old usual-usual.”

Through the North End Woodward Community Coalition, Ross started with solar-powered streetlights in neighborhoods that had literally been left in the dark. She’s adding solar-powered, wifi-equipped charging stations that have become neighborhood gathering spots. And a pilot program with the Honnold Foundation has put solar panels on 10 homes.

“Even the 10 we have, I can’t tell you what a difference it has made,” she said. One home, an all-electric house occupied by a 74-year-old woman on a fixed income, cost so much to heat the woman never could pay her entire electric bill. She’d pay a little each month, but knew she’d never catch up. Then came the solar panels, followed by a monthly electric bill of $59.

“So here’s a lady on a fixed income, struggling every month just to pay a little of her bill but never able to pay it off,” Ross said. “Now she can buy some groceries, even her medicine. So if you ask me about racial justice, I would say every low-income home needs solar on it.”

Rev. Ross, who hopes to someday equip a thousand Detroit homes with solar, acknowledges there are challenges. Michigan currently has a limit on the percentage of solar homes that can connect to the power grid. And Detroit houses often need work before solar panels can go up. Still, she’s a fan of Biden’s all-government climate approach.

Civilian Climate Corps

The Civilian Climate Corps harkens back to the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Great Depression program that put 3 million men to work building structures, and trails – most of which you can still see today – in state and national parks across the United States.

Patrick Doran, associate state director for The Nature Conservancy Michigan

This second iteration of CCC could similarly put millions to work making the country more climate resilient by installing solar panels, building green stormwater basins to slow runoff, or planting trees to capture carbon and cool cities.

In the Great Lakes basin, that could also mean restoring wetlands to absorb flood waters and sediment. Or naturalizing shorelines to reduce erosion. Or propagating fish species to improve biodiversity. The skills required could range from digging holes to developing computer models.

“It’s an incredible idea,” said Patrick Doran, associate state director for The Nature Conservancy Michigan. “To me it’s mainstreaming the conversation about the value of our lands and water. In the Great Lakes, every time we turn around we’re facing the water, facing the forest, facing the prairie. In the far north and even in cities, nature is nearby.”

Dave Spratt is a freelance writer and CEO of the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Speaking of Water: How Can the Biden Administration Deliver on Environmental Justice Pledges?

Intersecting Crises: Fighting for climate justice in a pandemic

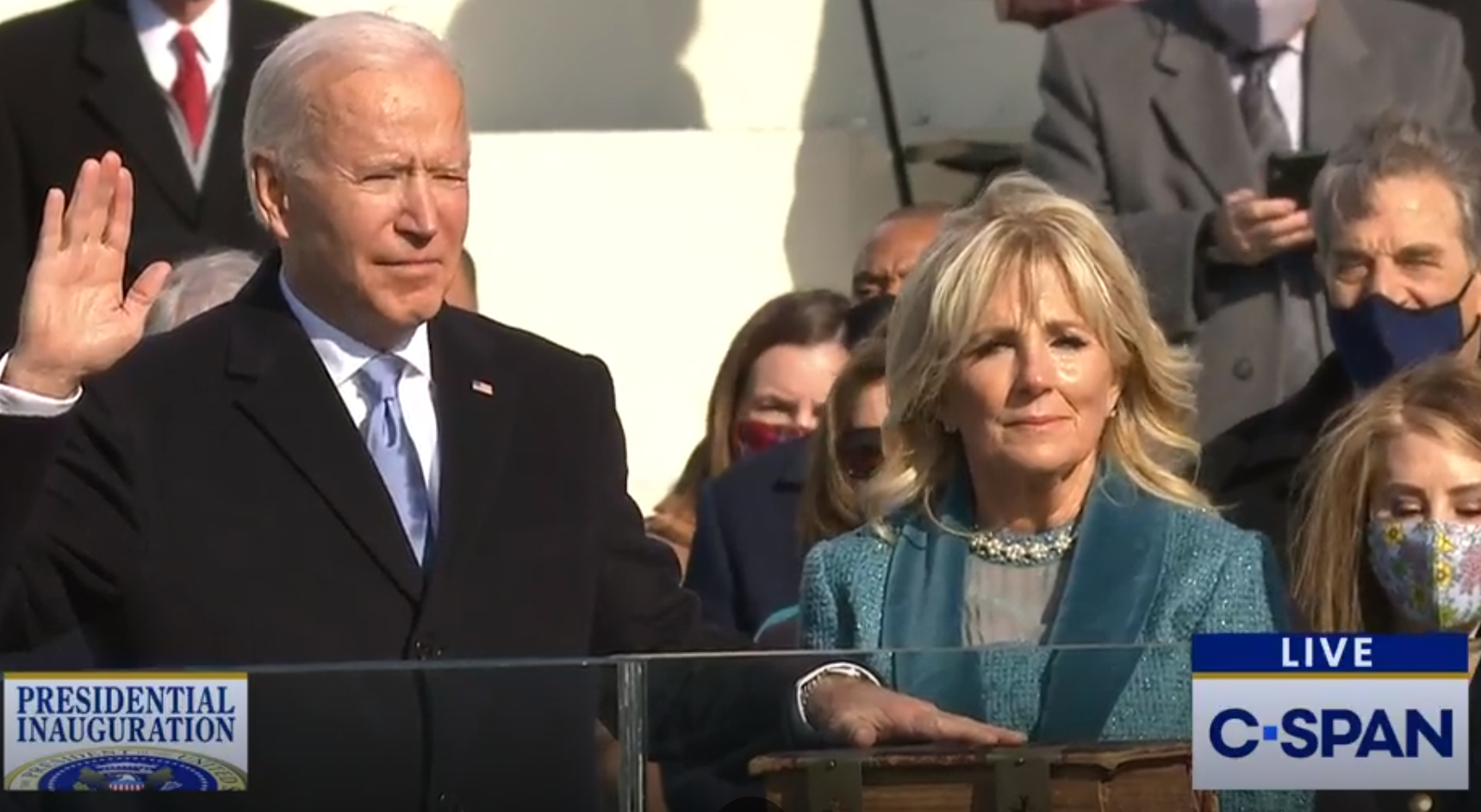

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Joe Biden is sworn in as president of the United States. (Photo courtesy C-Span)