Two simple, white signs marked “WPSC” on small posts are all that mark its existence to most of the public. The posts sit on either side of a narrow road that turns to gravel then disappears shortly after into the woods and is the gateway to the oldest continuously operating – and most storied – waterfowl hunting club in North America.

While great hunting has been a hallmark of the Winous Point Shooting Club for more than a century and a half, its true nature leans more toward innovation and conservation – especially since the creation of the Winous Point Marsh Conservancy two decades ago, a natural evolution for an organization some of whose members years later would also help establish the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

It was in 1856 that a handful of avid hunters and outdoorsmen from Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania established a hunting club on Muddy Creek Bay. A number of those gentlemen had been spending time in a downtown law office owned by Leonard Case, Sr., a well-known attorney and philanthropist. His sons, William and Leonard Case, Jr., operated their retired father’s business. The office was nicknamed “the Ark” because it was filled with pairs, male and female, of numerous species of mounted birds and other animals. While the men who gathered at the Ark were younger and had varied careers, all were deeply interested in wildlife and natural sciences.

Tod Sedgwick and Roy Kroll’s book on Winous Point is a tome on waterfowling and conservation.

Authors Tod Sedgwick and Roy Krolls’ book, Winous Point, 150 years of Waterfowling and Conservation (a massive, richly illustrated affair from Derrydale Press, 2010), describes the site: “The Ark was a filthy, haphazard combination of natural history museum and club with no bylaws, rules, regulations, no archives or records. It was situated in a two-room building. One room was an office turned into a gathering place and the other a tool room with drawers containing materials used for taxidermy. Legend has it that it was customary to clean the Ark no more than once a year, and that one year they forgot to clean it and cobwebs, filthy from soot, stretched from floor to ceiling. In its focus on hunting, natural history and fellowship, the Ark clearly was a precursor to the Winous Point Shooting Club, as well as the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.”

With $400 for 205 acres and $870 for a clubhouse, the 20 men established the Winous Point Hunting Club. And the rest is history.

Benefits of good stewardship

Andy Jones, curator of ornithology at the CMNH, said he’s made trips to the marsh for some years now.

“The invitation was kind of in recognition of the long connection between the two,” he explained. “In the founders of both, there were some names in common. There are names I see on specimen tags that are also shared with Winous Point folks. I know on our lower level, one of our exhibits is one of waterfowl that are supposed to be at Winous Point. I know the shooting club’s founders were comprised of wealthy folks and so were the museum’s founders. It wasn’t a big community, so it just made sense for those environmentally focused people to be pulled into both. We still share people, there are members of the Marsh Conservancy board who are also board members at the museum.”

Jones is now a board member of the Winous Point Marsh Conservancy and described Winous Point’s contributions to conservation and science as lengthy and significant.

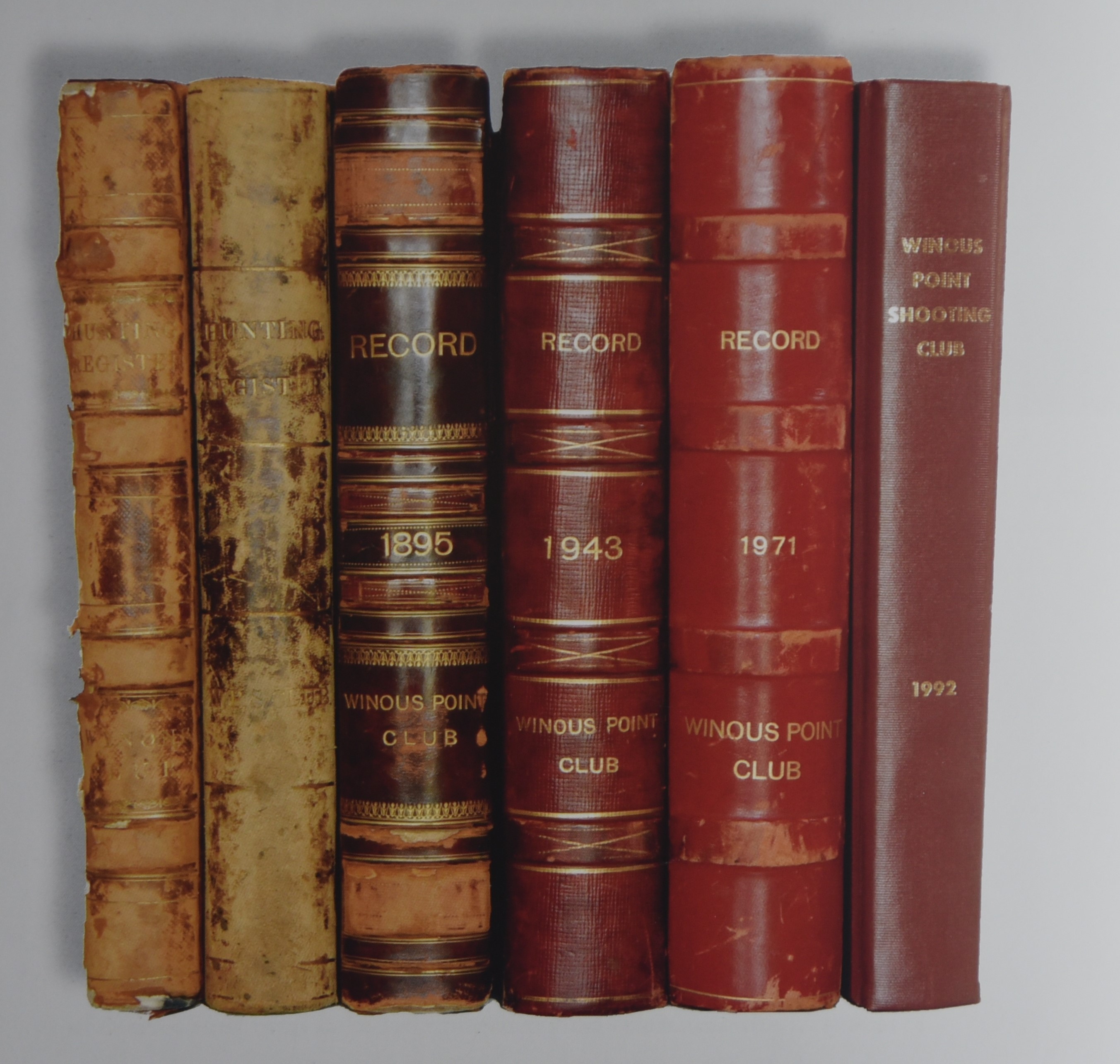

Over the years WPSC members and staff kept impeccable shooting records, a valuable and irreplaceable conservation tool. (Provided by Winous Point)

Since 1862 the Shooting Club has kept a meticulous record of waterfowl harvests, including which members took which ducks and how many. Less than a decade later some members were already looking toward the preservation of natural resources in the region as well as nationwide. This included Civil War financier and Shooting Club member Jay Cooke, who helped fund a series of lectures creating enthusiasm for the establishment of the nation’s first national park, Yellowstone.

While spring hunting wasn’t nearly as fruitful as autumn, it was practiced for a short time during Winous Point’s early years, though some members quickly soured on the activity since it intercepted birds aiming to breed. Member David Cross wrote in his 1880 book, Fifty Years with the Gun and Rod, “Spring shooting of ducks, especially those that breed here, should be prohibited by our game laws throughout the United States.”

The last record of ducks killed during spring at Winous Point was in 1884, two years before the club rules prohibited it and 35 years before the federal government outlawed the practice.

Cross also wrote about the changing attitudes of hunters: “But now, and for several years past a more exalted policy has prevailed, and the people themselves have taken the matter in hand; formed numerous sporting clubs; secured the passage of more stringent and effective game laws, and have shown a worthy and laudable disposition to yield a part of their private rights to the public good.”

For years baiting, using corn or grain to attract ducks, was a common and accepted practice among the many duck-hunting clubs in northwest Ohio. It began when duck populations plummeted in the early 1900s as a result of unregulated sport hunting and market hunting, where large numbers of birds were taken in commercial operations which sold ducks to retail markets.

While some Shooting Club members resisted, new laws eventually enacted prohibiting baiting, and lowering daily bag limits, among other restrictions. The membership as a whole eventually embraced them.

Member Chester Brooks, according to Kroll, persuaded members to contribute $50 each to More Game Birds in America, the predecessor to Ducks Unlimited. At one point, members were poised to fully support a closed season with no duck hunting, if federal scientists said it was needed.

By 1945, the Shooting Club began to incorporate wildlife biologists in its operations, thus beginning the constant study of the waters, ducks, birds, fish and flora of the marshes of Muddy Creek and Sandusky bays. Unpredictable fluctuations in Lake Erie water levels also meant an unprecedented era of stone-moving, earth-moving and dike-building would soon begin.

Many wide-ranging achievements at Winous Point

Jones describes Winous Point as a remarkable place. He was reluctant to cite a single notable achievement, instead noting there are many.

“I feel like it’s really a body of work. Early on it was very duck-focused, and now instead of taking away that focus they’ve expanded into non-game things. They’ve really been doing work that’s led to contributions to the bigger picture about how to manage waterfowl correctly for the entire continent,” he said. “Winous Point has been contracted to analyze data at the state level on banded ducks harvested by hunters,” going on to say the ODNR implicitly trusts the organization’s scientists and science.

Modern efforts at controlling invasive species include expensive air applications. (Provided by Winous Point)

In recent decades a multitude of research topics have been facilitated by Winous Point, including

- mercury, cadmium and selenium accumulation in eggs and chicks of great blue herons,

- use of northern pike to control carp,

- dietary and reproductive habits of Blanding’s turtles,

- DDT in marsh ecosystems and in waterfowl,

- factors affecting reproductive success of common terns,

- and dozens of others.

Brendan Shirkey, research coordinator for the Marsh Conservancy, said he and other researchers assist the Ohio Department of Natural Resources and Canadian scientists on projects.

“We do a lot of wetlands research that has nothing to do with ducks or duck hunting, and that’s the way the trustees want it,” he said. “One of the really big projects they did out here was on drawdowns and how succession happens in a wetland and what vegetative response is when you draw water levels down. That’s a lot of the management we do now and a lot of the management that’s done all over the country. Wetlands are meant to be dynamic and changing. That was some of the first work ever done on drawdowns. That was, I think, the vision of the trustees with the research program. It’s great that we can manage our own 3,000 acres the way we want to provide healthy, high-quality wetlands, but through research hopefully we can have an impact far beyond our borders.”

Seining for macroinvertebrates at Winous Point during Day on the Wild Side. (Provided by OSWCD)

A marsh that never shrinks

“Right now it’s close to 3,500 acres,” said John Simpson, executive director the Marsh Conservancy. “It’s the largest privately held marsh in the region.”

And, Simpson said, it’s always growing.

“We’ve slowly been adding to it,” he said. “We just purchased a small parcel last year and a larger parcel, about 400 acres in Sandusky County, about 10 years ago. Slowly but surely we’re adding to that acreage. The Marsh Conservancy works to protect all that acreage under permanent conservation easement.”

According to Simpson, about half the acreage gets hunted during waterfowl season and the other half rarely. And speaking of rarely, the once-rare American pelican has been showing up in greater numbers at Winous Point every year. So have sandhill cranes, which now nest and breed on the marsh. Also showing up at Winous Point in greater numbers are people.

“We host a lot of meetings and classroom events for Ohio State and Hocking College and other nonprofits like Ducks Unlimited and Pheasants Forever,” Simpson said. “The Division of Wildlife uses our facilities and there are a few women’s events the Ottawa Soil and Water Conservation District puts on out here. The research program is probably the biggest thing. Last year I think we had 14 students and technicians living at our place doing research on eight different projects from Blanding’s turtles to king rails and herons, and duck and waterfowl projects, of course. And we just wrapped up a bunch of shore-bird projects.”

Schott described Winous Point’s role in conservation as ever-expanding as its former interns and research students graduate from their universities and enter into careers.

“I’m not sure how many students they’ve had since the inception of the program, but there’s been hundreds of kids over the years that drove down that long lane and left with a lot of experience and knowledge,” he said. “There’s a lot of them here in Ohio but they’re all over the country, with the USFWS, Ducks Unlimited or other wildlife services. It’s pretty amazing how many folks are out there when you talk to them and end up finding out they worked at Winous.”

Seining for macroinvertebrates at Winous Point during Day on the Wild Side. (Provided by OSWCD)

A storied marsh opens to the world

While the Shooting Club delivered nearly a century and a half of fine hunting and ever-improving marsh management, it also blossomed into a site that produced a long line of conservationists with its internship program. This program, which began in 1983, saw two college undergrads spending six months on the property each year performing all manner of work, including maintenance, improvements and various wetlands projects.

It was the 1999 morphing of the longstanding Winous Point Research Committee into the Marsh Conservancy that saw research project numbers grow quickly on the property. The new Marsh Conservancy, a nonprofit with a focus on science and education, saw a renewed and extensive focus on the preservation, improvement and sometimes acquisition of wetlands in the region. The move opened the site to a new avenue for the future of wetlands in the region and, as a result of research, wetlands nationwide.

“Ever since the inception of the Marsh Conservancy they’ve really opened their doors,” said Jim Schott, a former intern who now oversees the Ohio Department of Natural Resources’ 3,200-acre Pickerel Creek Wildlife Area. “I was around in the ‘90s and back then Winous Point was kind of a quiet place, it was just a shooting club. Yeah, they brought in interns and there were some masters students from Ohio State, but once the conservancy was developed they really opened up the doors.”

Day on the Wild Side attendees record data after capturing birds at Winous Point. (Provided by OSWCD)

A Day on the Wild Side is one example of Winous Point’s vision. The annual summer event (canceled last year and likely this year due to COVID-19) brings in kids from all over northwest Ohio to experience everything Winous Point has to offer. That includes activities like bird banding, fishing, shooting shotguns and rifles, archery, a trip through the marsh on a punt boat and, of course, pizza.

“It’s a day geared around getting kids outside and learning what we have here right in our own back yard,” said Joe Uhinck, who also interned at Winous Point and is now a district program technician at the Ottawa Soil and Water Conservation District. “We get their feet in the water and they get the feel and touch, the whole experience of the marsh as well as the other experiences.”

Uhinck said it’s especially nice to see kids show up who have little to no outdoors experience.

“That’s one of the greatest things, getting kids with different backgrounds, different experiences,” he said. “Just about everyone that does it leaves pretty excited and pretty happy. They learn a lot of new things and always want to come back.”

Sandusky County Park District Research Coordinator Tom Kashmer spends time at Winous Point working both with birds and people.

“Three times a year I lead tours for the public out there and go through the clubhouse, give them the history of the club. Most people think of hunt clubs as just a hunting club, where Winous is so different than other clubs,” he said.

Kashmer’s job currently involves pulling several duck species from marsh traps where he bands them and records data before releasing them. Kashmer hosts workshops, including at Day on the Wild Side, where songbirds, warblers and other birds are netted, banded, analyzed and then released.

“I’ve banded hundreds of redheads, maybe 50 canvasbacks over the years, ring-necked ducks, shovelers, gadwalls. And I couldn’t think of a better way to get kids involved with nature than bird-banding,” he said. “They actually see, and in most cases actually hold, wild birds that most people don’t even know exist. The looks on faces are pure joy and excitement.”

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

PFAS is in fish and wildlife. Researchers prowl Michigan for clues.

Fisheries Fight: Michigan commercial fishers bring MDNR rules to court

Unexploded Ordnance: Lake Erie shoreline site of long-term munitions study

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Family gatherings on the marshes have long provided recreation outside duck hunting. (Provided by Winous Point)

1 Comment

-

What a great article,thank you I enjoyed it