The watersheds that feed the Western Basin of Lake Erie are home to thousands of crop and livestock farms. Those farmers use underground systems to manage rainwater, including many located where a massive swamp once made up the Ohio landscape.

All those farms face challenges managing fertilizers and water in their fields with drainage systems. The level of success at managing those challenges can be seen in the size and severity of the yearly harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie.

And while both farmers and scientists work to reduce nutrients leaving agricultural land, the competing interests of agriculture and conservation often seem at odds when it comes to managing the problems. The unpredictability of seasonal weather does not make it any easier.

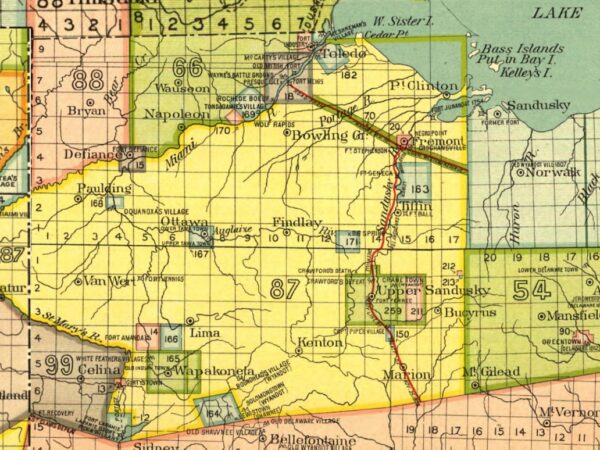

Encompassing about 1 million acres in northwest Ohio and northeast Indiana, the Great Black Swamp was an impenetrable morass of marsh, mud and gunk. A corduroy road, named so for its construction of logs laid side-by-side, offered settlers the first path through the swamp between Fremont and Perrysburg. They eventually installed pass-throughs beneath the road to allow the free flow of water to Lake Erie.

Watch Great Lakes Now’s segment on the Great Black Swamp:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.“It was an absolute terrifying wilderness,” explained Clint Mauk, historian and author. “Water and soft mud, and you couldn’t drive a wagon through it and horses got stuck up to their bellies in the mud.”

By the 1860s residents had begun draining the swamp by hand, digging ditches on field edges and installing drainage systems which fed the ditches. The very first systems were made of wooden boards set in an upside-down ‘V’ shape and buried in trenches. Then came clay pipes, or tiles, in a variety of designs. While the region had just five tile factories in 1870, it was home to more than 50 by 1880. By 1884 the state’s agricultural board estimated there were 109 miles of field tile installed in Paulding County alone.

One of Myers Farms’ soybean fields. Myers operators say they do everything in their power to raise crops responsibly and help protect Lake Erie. (Photo credit: James Proffitt)

In 1893 Bowling Green resident and inventor James Hill designed a high-tech machine that would transform the region with great speed. A single machine could lay 1,800 feet of tile in a single day. Within decades of his steam-powered Buckeye Ditcher entering the scene (patent #523,790) in 1894, only remnants of the swamp remained – the rest was on its way to becoming fertile farmland.

New clay drainage tiles replaced or augmented earlier versions. Fields that were originally tiled in 100-foot intervals often received additional drain tiles which shortened the distance between them for faster draining. Water from these fields sometimes drained directly into adjacent streams, though most often they drained into man-made ditches. The water from those streams and ditches eventually poured into Lake Erie. A census revealed that by 1920, Ohio had 20,000 miles of drainage ditches, with 15,000 located in northwest Ohio.

According to Mauk, some portions of the original drainage are still visible where the Great Black Swamp once was.

“The remnants are ditches. Wood County still has 3,000 miles of ditches they maintain. Thousands of miles of ditches to get the water out, which eventually ended up in Lake Erie and it still does today, and that’s part of the problem,” he said.

Currently about 4.5 million acres of northwest Ohio and southeast Indiana farm fields drain into the Maumee River, then Lake Erie. That’s in addition to nearly a dozen other rivers in Michigan and Ontario.

Every year, more drainage is added and some of the existing drainage is improved. But in recent years, changes in the way farmers operate their drainage systems may have an impact on nutrients loss. And it’s impact on Lake Erie is a debatable topic.

Essential tool

Despite the fact that subsurface drainage systems have often been frowned upon by conservationists, they remain an essential tool for anyone raising crops on acreage with little natural drainage. And that’s pretty much all of northwest Ohio. Their effect on nutrients loss can vary from field to field, but the increasing popularity of drainage control structures is improving their usefulness as both a production tool and as a conservation tool.

“In Wood County there isn’t an acre in the county that doesn’t have some sort of subsurface drainage in it,” said Jeremy Gerwin, a technician for the Wood Soil and Water Conservation District. “Anywhere the land was cleared 100 years ago or even longer, the general practice, even if it was just hand-dug, was to create some type of drainage. Whatever it took to make it farmable.”

Gerwin said that relics of the early clay pipes installed in the 1800s and up to the mid-1900s still remain in many Ohio farm fields.

“Clay tiles and some cement tiles kind of hung around until maybe the early ‘80s, but everything’s been plastic since then,” he explained.

Although for the past half century they’ve been made of plastic instead of clay, the underground systems used to drain water from farms is still called field tile.

Ohio farm (Great Lakes Now Episode 1016)

Drainage systems have become more deliberate

The discussion about field tiles is a complicated one.

“None of the answers are as straightforward as you’d like, unfortunately,” said Laura Johnson, director of the National Center for Water Quality Research. “The whole region has been tile drained for a very, very long time. What’s really changed since the mid-2000s when corn prices were really good, is that it seemed like a lot of farms that would have randomly placed tile, like ‘Oh here’s a wet spot let’s drain that,’ they went on to more systematic grids of drain tiles because there’s a clear connection between improved yield and improved tile drainage.”

If a farmer has extra cash during good years, why not install better drainage and improve yields? It only makes sense in the long run, Johnson said.

Field tile has long been thought to exacerbate the Lake Erie algae issue by speeding nutrients from the application process to ditches, streams and ultimately Lake Erie.

“I think right now, field tiles are bad for water quality especially when it comes to sediment losses because it essentially lets water leave fields really quickly,” Johnson said. “Basically we lose more water than we would have normally, where some of that water would have been stored up on the field and now it moves out faster.”

And the higher volume of moving water moving faster is an issue because it’s carrying nutrients, she said.

“But without tile drainage, the question becomes ‘Where would the water go instead?’ At least with tiles drains, some of the nutrients are filtered,” Johnson said.

Johnson said what she and other scientists know for certain now is that most nutrients are being delivered through tile drains because they are running constantly unless drought conditions prevail.

“And I don’t think we’re going to see a reduction in tile installation, especially here because of these bigger and more intense storms,” she said, citing climate change.

Tile installation is a steady business

Steve Harder operates HMG Drainage in Oak Harbor, Ohio. He says tile installation is a steady business in northwest Ohio – and it’s not your grandfather’s tile installation.

The installation itself is one-stop shopping, according to Harder. A single machine can do it all in one fell swoop.

“To say the least, it’s amazing. It’s all GPS-driven, the lines, the grade control. We just bought a used machine for $400,000. We pull from 18 U.S. and European satellites that control the machines at all times – and that’s not a free service,” he explained. “A typical installation would run somewhere around $1,400 an acre.”

Based on the in-field survey, a computer figures the locations of the tiles, the grade of the tiles, everything. Harder said depending on the price of crops, an average increase of 12 to 25% in yields could be expected. For farmers, that brings income fluctuations previously weather-dependent under control. He likened it into an every-year insurance policy on production.

Tiles ultimately control water table – with help of water control structures

“The water is actually coming into the drain from the bottom half of the tile, not the top half,” Harder said. “Drain tile actually works to keep the water table from coming up too high. It’s a common misconception that drain tiles drain the water from above it.”

The tiny, myriad perforations collect water, which runs downhill and is fed to larger, edge-of-field tiles, which lead to field-draining sites. Those sites are increasingly populated with drainage control structures (DCS) to help manage water flow. Once water passes through a DCS it runs into a ditch.

“In Wood and Henry counties we’ve had a lot of farmers installing DCS now,” said Gerwin. “They can regulate their amount of flow during winter months and cut down on the potential amount of nutrients that can be lost in the water.”

He said managing DCS is done manually with the raising or lowering of plastic boards, keeps needed water beneath the crops and their roots when water is scarce, and lets it out when there’s too much. It also aids in drying fields out to allow for spring planting.

Before DCS were popular, water from fields flowed solely under gravity and with little restraint.

“We’ve probably had 500 installed in Wood County since 2012,” Gerwin said. “Through the H2Ohio program we’re scheduled to install about another 100 this year.”

Toxic algae blooms around the Great Lakes in the summer. (Great Lakes Now Episode 1013)

Is there an overall benefit from DCS? It depends

Harder said there is, because of basic chemistry.

“Algae blooms are fed by phosphorous, and when phosphorous is applied to a farm field, ultimately the phosphorus and soil particles attract to each other,” he said. “The most likely way that phosphorus will make its way into the watershed is if the soil moves.”

Harder said he believes field tiles actually improve soil retention.

“When you’re placing these tiles, you’re 30 inches deep into the soil, and it’s just not moving much down there,” he said. “Then to go back to my earlier point, which is that drain tile actually keeps the water table from coming up and, with that being said, the water is actually coming into that drain tile on the bottom half, not the top.”

With DCS, controlling the flow of water and the water table are primary functions. And with these two functions, it’s not difficult to see possible conservation benefits.

A 2016 Manitoba Agriculture study found that DCS “increases the ability to manage the depth of the water table and conserve water in the root zone, reducing overall outflow and loss of nutrients.” The study also found that DCS can protect against over-drainage, store rain for dry periods and lower the water table during wetter periods.

The study went on to cite improved soil structure, decreased compaction and the ability to mitigate many intense precipitation events as likely benefits.

“Drainage control structures should help thwart some of those things, though there are caveats,” Johnnson explained. “One is that when we need them to be holding back the most water, they’re often free-flowing because fields need to be drained for farm equipment to get on, that would be early spring. There’s no reason for a drainage control structure to reduce the concentration of phosphorous in water when you could just reduce the amount of water going downstream.”

But Gerwin said reducing water flowing out is one of the practical benefits of DCS: water conservation. Which in turn, he said, can translate into less nutrients loss overall.

“Shortly after you plant and things begin to emerge and are effectively growing, you’ll start putting boards back down in those structures to raise the water table. That can help in drought conditions,” he explained. “With the gravity-fed water following a drain slope, a water control structure placed on the main outlet allows farmers to control the water height in a field.”

That, he said, allows maximum water usage, and maximum amounts of nutrients kept in field soil and utilized by crops.

How farmers apply fertilizer is a big deal

Exponentially less fertilizer – both commercial brands and livestock manure – would be great, according to Johnson.

“But that depends on whether you’re trying to be realistic or not. So yeah, if we stopped applying phosphorous and didn’t expect to have great crops,” she said. “I don’t think anyone would say that’s a reasonable way forward. All the data indicates that at least for commercial fertilizer, rates have gone down, a lot of farmers are applying less.”

She said one of the most important factors is the Lake Erie nutrients issue is exactly where farmers apply their fertilizer.

“I would say more simply, if we get phosphorous off the surface that should fix a lot of our issues and that should negate drainage being an issue at all,” Johnson said. “Yeah, there’s a lot of phosphorous being lost through tile drains and that probably increases with increased usage of the drains.”

That’s why injecting fertilizers into the soil instead of broadcasting on the surface is so important, she said.

In northwest Ohio, more and more farmers are turning away from broadcasting fertilizer and toward the practice of injecting in their efforts to reduce nutrients leaving fields. But such equipment is expensive, especially for livestock farmers using manure. Manure injection tools, even used, can cost upwards of $200,000.

Farm (Great Lakes Now Episode 1013)

More DCS, less fertilizer

Gerwin described DCS benefits as both agricultural and environmental.

“In the winter months you would raise the water table to promote both nitrogen and phosphorous that could be in the soil to attach to soil particles,” he said. “Otherwise, those nutrients could potentially be going out the drain tiles.”

According to Gerwin, the Natural Resources Conservation Service offers programs which focus on installing DCS.

“They have programs for installing them and the local districts promote them,” he said.

The structures cost about $1,000 for a 6-inch and about $2,500 for 8- or 12-inch.

“We’re farmers, also, and so the whole situation kind of hits home with us,” said Harder. “We do everything we can. We buy from The Andersons and these buyers we deal with, their phosphorous sales have gone down 46%. We spend dollars upon dollars on application monitors and things of that sort, and soil sampling so we don’t over-apply nutrients. If it only takes 15 pounds of fertilizer per acre to produce a crop, why would we want to use 30?”

Read more news on Great Lakes Now:

“Saving the Great Lakes”: National Geographic December issue explores the lakes and their struggles

One Michigan county tells the story of a nation plagued by water pollution

Total Maximum Daily Load: Court case looks to push for Ohio EPA nutrients limit for Lake Erie

Cost of Conservation: Needed systems and equipment can lead to a hefty price tag

Water and Wonder: Great Lakes Now producer talks the lakes and his work covering them

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Ohio farm (Great Lakes Now Episode 1016)

1 Comment

-

I appreciate this information about field tiles. My brother is thinking of starting a farm. I’ll tell him to read this article so he can learn about field tiling for his farm.