For President-elect Joe Biden, the environment and climate change as campaign issues weren’t tucked away in an obscure position paper. Neither was his intent to focus on environmental justice if elected.

Biden also put a spotlight on President Trump’s rollback via executive order of nearly 100 environmental protections in his four years.

Dealing with those issues at any juncture would be a tall order for an elected official, but Biden also inherits the COVID-19 pandemic, a struggling economy plus a political climate that remains polarized.

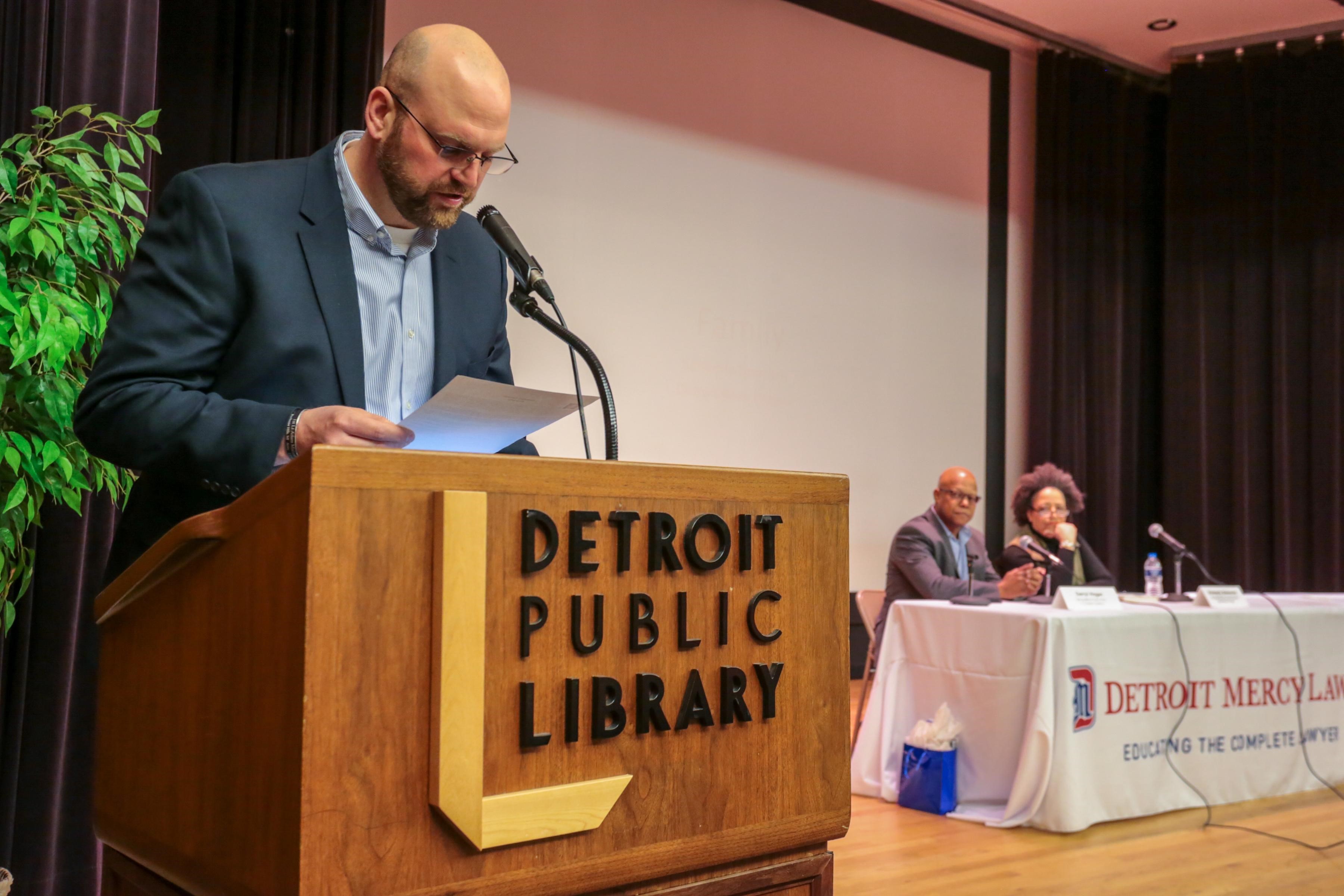

To help understand the policy and political challenges Biden faces, Great Lakes Now talked with University of Detroit Mercy environmental law professor Nick Schroeck.

Schroeck, who focuses on urban environmental law and policy issues, talked about the opportunities and legal challenges Biden will have in trying to reverse Trump’s rollback of environmental protections.

On climate change, Schroeck says the easy part will be rejoining the Paris Climate Accord. He also explains how his international law students see the issue.

And Schroeck says the federal focus on environmental justice had its origins in the administration of President Bill Clinton, but since then there’s been a lot of “happy talk” from politicians.

The interview was conducted by Senior Correspondent Gary Wilson via phone and email. It was recorded, transcribed and edited for clarity.

Great Lakes Now: After taking office in 2017 President Trump, citing regulatory overreach by his predecessors, began an aggressive program to scale back environmental protections. He bypassed Congress and issued executive orders. What gives a president that authority?

Nick Schroeck: Presidents are granted broad powers under the U.S. constitution and typically executive orders rely on that constitutional authority.

Presidents can issue executive orders and they are binding on federal agencies and the federal government. If there were previous executive orders from the Obama administration or from other presidents that President Trump didn’t agree with and wanted to alter, he could do that through his own executive order. That’s a way to bypass Congress on a lot of matters. However, executive orders can’t overturn legislation.

GLN: President-elect Biden now inherits those environmental rollbacks and has said that reversing them is a priority. What are his options?

NS: Executive orders are binding on federal agencies, but a new president can issue his or her own executive orders that would rescind or invalidate President Trump’s orders. So you can have a dance where a new administration cancels out the orders of the previous one. That’s similar to what Trump did with several of Obama’s orders.

It’s a back and forth that isn’t great from a policy perspective. Promoting renewable energy or retiring old coal-fired plants and dirty types of energy are policy decisions that require time to implement. You don’t want to be switching back and forth every four years on those national policies.

GLN: A signature piece of Biden’s campaign was addressing climate change and returning the U.S. to the Paris Climate Accords. Is that a quick fix for Biden or a protracted process?

NS: The Paris climate agreement is something where the U.S. withdrawal ordered by President Trump was a lengthy process that took over a year. Getting back in could be done by Biden on his first day on Jan. 20.

He could sign an agreement committing the U.S. government to the Paris accord, and it isn’t subject to the consent of the U.S. senate. I believe there’s a 30-day window for that to take effect. It’s a much quicker process to return to the agreement than it was to exit, and that was intentional on the part of the signatories. So it’s a quick fix to get back in the Paris agreement, but the tougher nut to crack is actually reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.

That means you have to come up with a way over time to reduce our reliance on fossil fuel for generating electricity and transportation. Those are decisions that will likely require action by Congress in addition to areas where Biden may be able to issue an executive order.

GLN: Expectations for action on the climate and clean water by Biden will be high from activists. As an attorney who navigates a maze of federal and state laws and regulations, what’s your advice to those who may have little patience for the regulatory process?

NS: It can be frustrating because there are a lot of processes involved and steps that have to be taken either to implement a new law or regulation or to rescind previous ones.

In administrative law, there are procedures that do good things like giving the public notice on a draft permit or when there’s a decision the federal government is making. We have the ability to know about it and to comment. However, there are also procedures that make it a protracted process in terms of changing existing rules and regulations through an administrative process.

Those of us who work closely with environmental law and policy have to take a long view because these processes are important. Before the federal government takes action that could harm the environment, we want the government to stop and think about the consequences of their actions. On the other side of if you’re trying to change rules and regulations that have been passed, there’s this thorny process you have to go through to unwind regulations once they’ve been approved. It takes time and we need patience in this area.

However, there are certain issues like climate change where we can’t be patient and we have to demand action. Biden campaigned on climate change and won the popular vote by a wide margin, so the expectation is that he’ll move aggressively on climate change.

GLN: Most climate change programs like Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s are focused on aspirational goals to be met by 2050. People are coping with COVID-19 and are struggling financially now. How does the Biden team convince the public that an emphasis on climate change should be an early priority?

NS: The response to and recovery from COVID-19 should rightly be the most important issue on day one of the Biden administration, and that includes providing financial support for individuals and state and local governments.

But in terms of major policy action beyond COVID-19, I expect climate change to be one of the administration’s main focus areas. While the long-term goals may seem aspirational, we have to set targets and then reduce emissions over time to meet those targets.

In addition to policy, the federal government can lead by example on climate by selecting clean energy suppliers and structuring federal grant programs so they are designed to increase investment in renewable energy technologies.

Those things can be done without Congress and without disruption to the COVID-19 response.

GLN: How do your students see the current state of environmental law at the federal level, especially related to climate change? Are they optimistic that the current framework will work, or do they see a broken system that needs to be remedied?

NS: It’s interesting, one of the things at Detroit Mercy Law is that we have a dual degree program with Canadian national students who take classes at Detroit Mercy and at the University of Windsor law school. My current environmental law class has 51 students, and half are Canadians. That’s led to interesting discussions because from their perspective, it’s ‘What’s taking the U.S. so long to get its act together on climate change?’

In terms of U.S. students, there is a broad consensus that climate change is something that they’ll face throughout their careers, so they want aggressive action. They have a commitment to vote in a way that looks at a candidate’s climate policies, and they’re working to hold politicians accountable. They are not apathetic, and they’re demanding that the federal government take aggressive action on climate change.

GLN: Post-Flint water crisis and during COVID-19, there has been an increased spotlight on environmental justice. Biden has pledged to focus on remedies for the inequities that people in environmental justice communities endure. You’re close to EJ issues in Detroit, so realistically, what can a president do?

NS: The federal government began to focus on environmental justice concerns after an executive order drafted by President Bill Clinton. He signed that order after years of pressure from the Congressional Black Caucus. His order directed federal agencies to consider environmental justice impacts in their permitting decisions and regulatory review processes. That was a big leap forward.

There’s a lot that a president can do through executive orders and also in the federal budget where investments are made.

President-elect Biden will look at the types of programs that he helped oversee as part of the recovery act in the Obama administration. I expect federal incentives in areas like renewable energy. If we are able to transition dramatically to electricity generated from wind and solar and other renewable sources, then we can continue to shut down older, dirtier power plants and the benefits will flow to environmental justice communities.

It’s important to have a president talking about the environmental injustices that continue to be present in our society. To understand that it’s a challenge for kids to go to school across the street from a steel mill and that they are on the receiving end of higher amounts of pollution than children in other areas.

It’s important to have a president who recognizes that and is willing to work towards solutions. Lip service will not be enough. These are communities that have heard a lot of happy talk from politicians for decades, and they deserve action.

Read more on politics at Great Lakes Now:

Regulatory Rollbacks: Loss of federal water protections impacts Great Lakes region

COVID-19 Compliance: Agencies grapple with environmental protection in the COVID-19 era

Green group endorsements fail to push non-incumbents into Congress in the Great Lakes

Who in the U.S. Is in ‘Plumbing Poverty’? Mostly Urban Residents, Study Says

What Has the Trump Administration Meant for Water?

Featured image: Nick Schroeck speaking at the Detroit Public Library (Photo Credit: Meghan Petibrin, courtesy of Nick Schroeck)