This article is published in conjunction with PBS’s “The Age of Nature” series which begins airing on Oct. 14.

Join Great Lakes Now‘s “Shipwrecks and ecosystems in the Great Lakes” watch party on Facebook on Monday, Oct. 12, at 7 p.m. EST. A maritime archaeologist with NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and a benthic ecologist with NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory will be participating in a Q&A. Click here for more information.

All that remained of the schooner was a bit of its hull – a tightly packed row of wooden planks stretching 40 feet across the bottom of Lake Huron. Sunbeams easily penetrated the 20 feet of clear lake water above the wreck.

The site appeared lifeless.

There were no schools of emerald shiners, black-striped minnows or yellow perch in sight. The wooden planks were not covered with algae nor encrusted with zebra or quagga mussels. So, the sudden appearance of a bass approaching at warp speed took the diver completely by surprise.

A 3-foot smallmouth bass was using the wreckage as a nest site, and the aggressive male was undeterred by the diver’s larger size. It attacked at full speed, making direct contact with the diver’s underwater camera.

Only when the diver slowly backed away did the smallmouth retreat to its nest at the far end of the wreckage having successfully deterred another visitor to the site.

That’s just one example of the kind of interaction divers can have with the underwater wildlife around Great Lakes shipwrecks.

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Shipmates

Together, the five Great Lakes contain upwards of 6,000 shipwrecks. These vessels are scattered across the entire Great Lakes from the Thousand Islands on the eastern end of Lake Ontario to Duluth on the western end of Lake Superior.

“Wrecks create little ecosystems because you’ve got all these little nooks and crannies,” said Mike Thomas. “The structure supports arthropods and isopods at the bottom of the food chain. Those species attract small fish and the big fish come in to eat the little fish.”

Thomas recently retired after 30 years as a Michigan Department of Natural Resources research biologist, so he’s very familiar with the habits of Great Lakes fish.

“Smallmouths like to nest near structures,” Thomas said. “A lot of times you’ll find they make their nests next to some bullrushes or a piece of wood. Something other than just a flat open bottom. They like that.”

However, temperature is the primary factor that determines where fish go, Thomas said.

Coldwater species like whitefish and salmon spend the summer in deep water and the winter in shallower water, while species like freshwater drum and muskellunge prefer warmer, shallower water, he said.

“We see different fish at different depths,” said Brian Bangert, former president of the Neptune Club in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Neptune is the oldest dive club in the state of Wisconsin and Bangert, like most of its members, is an avid Great Lakes shipwreck diver.

Perch (Photo credit: Polka Dot Perch)

The Fleetwing (25 feet), Lake Michigan

On Sept. 26, 1888, the schooner Fleetwing was running under full sail in a heavy fog. The ship was heading for the Death’s Door Passage into Green Bay. Tragically, the captain misread a shoreline landmark and, thinking they had reached the expanse of Green Bay, he sailed the ship full-speed into tiny Garrett Bay and straight up onto the beach.

When the lake levels were lower, Bangert said a portion of the Fleetwing could be seen sticking out of the water nearshore. Today, the shipwreck is resting in 11 to 25 feet of water.

The quiet, shallow water in Garrett Bay is ideal for crayfish and the Fleetwing offers these freshwater crustaceans a wide variety of locations to hide out, catch prey and reproduce.

“There are tons of crayfish on the Fleetwing,” Bangert said. “And gobies. And gold.”

A few years back, Neptune Dive Club members threw $40 worth of gold coins onto the Fleetwing wreck site as part of a charity fundraising treasure hunt. Only $3 were recovered during the event.

“So, there’s still $37 worth of gold out there,” Bangert said with a laugh.

The Frank O’Connor (70 feet), Lake Michigan

On Oct. 3, 1919, the bulk carrier Frank O’Conner was nearing its destination of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with 3,000 tons of coal from Buffalo, New York. On a prior voyage, the ship had carried 100,000 bushels of grain which had left a thick layer of highly-flammable dust inside the ship.

At 4 p.m., a fire broke out in the bow.

The captain ordered the helmsmen to steer for shore. Two miles off the Door County shoreline, the steering mechanism burned through, the lifeboats were launched, and the ship was abandoned. The vessel burned for several hours before sinking in 70 feet of water.

Thermoclines mark the point where warm surface waters meet colder, deeper waters. A thermocline can be as shallow as 5 feet like in a backyard pond where the surface feels warm but dangling feet feel cold. In the Great Lakes, shipwreck divers often pass through two or three of them depending on how deep they go.

Seventy feet below the surface, Lake Michigan is perpetually cool.

“On the O’Connor, the salmon line up under the bow,” Bangert said as he explained how a large group of salmon typically use the O’Connor’s wreckage for shelter.

“And you usually see schools of whitefish and shad off in the distance,” he said.

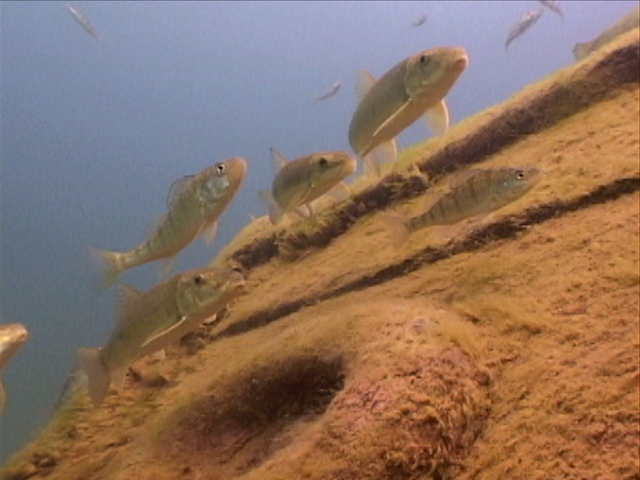

School of fish (Photo credit: Polka Dot Perch)

The schools move away from the wreckage when the divers arrive, though they don’t leave the area entirely, according to Bangert. Divers can usually see flashes of silver as the schools circle the shipwreck from afar.

Thomas is not surprised that fish, particularly schooling species, seem to avoid divers. He said fish have a lateral line that acts as a sensor and allows fish to detect the tiniest movements in the water. Schooling fish use their lateral lines to maintain tight formations.

When divers exhale, they release an explosion of bubbles into the water column. This disruption would likely be “very noisy” to fish, Thomas said, adding that species that prefer to travel in large schools might find the divers’ bubbles particularly annoying.

The E.R. Williams (110 feet), Lake Michigan

On Sept. 22, 1895, the schooner E.R. Williams was under tow near the mouth of Green Bay when a storm set in. Bangert said the tow line was cut and the Williams was left to flounder. It sank in 110 feet of water.

In addition to being perpetually cold, little sunlight penetrates 110 feet under Lake Michigan.

“It’s definitely dark,” Bangert said. “Cold and dark.”

Burbot or freshwater cod, sometimes called lawyer fish, are the most frequently seen deep-water shipwreck species in the Great Lakes. After 100 feet, “lawyers” are usually the only fish divers see, according to Bangert.

“On the Williams, the burbot line up along the gunnels. When they swim away, they leave little trails of silt,” he said. “It looks really cool.”

The William P. Rend (17 feet), Lake Huron

On Sept. 22, 1917, the wooden freight barge W.P. Rend was carrying 2,300 tons of crushed limestone. The Rend was under tow by the tug Harrison. As they neared Thunder Bay a heavy surge of lake water pushed the Rend into shallow water where it floundered and sank.

Today, the Rend sits in 17 feet of water. The wreckage is mostly intact with the ship’s sides extending to within a few feet of the lake’s surface.

Thunder Bay, on the northwest coast of Lake Huron, is a popular shipwreck diving destination. This area claims to have the highest concentration of wrecks in the Great Lakes, earning it the moniker “Shipwreck Alley.”

Thunder Bay was the first of 13 underwater preserves currently designated in the Great Lakes.

Joe Sobczak owns Thunder Bay Scuba in Alpena, Michigan. Sobczak has been running shipwreck dive charters in Thunder Bay for 20 years.

“If you want to see fish, dive the Rend,” Sobczak said.

“If you get down there on a clear day, you’re like the little diver in the fishbowl,” Sobczak said. “The gravel bottom looks just like an aquarium and you’ve got fish swimming all around the wreck with plants growing up through the gravel. It’s a great dive.”

Warm-water species like bass, perch and suckers spend their summers in shallow water, Thomas said. Many juvenile fish also hide in shallow-water grass beds. He said a shallow water shipwreck with native grasses would appeal to a wide array of warm-water species.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on shipwrecks in Thunder Bay here:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Oscar T. Flint (33 feet), Lake Huron

On Nov. 24, 1909, the 240-foot wooden steamer Oscar T. Flint pulled into Thunder Bay for some minor engine repairs. The ship was bound for Duluth with a load of limestone. The Flint was towing the barge Redington, which was also filled with limestone.

The following night, the Flint’s captain was awakened from a sound sleep by the smell of smoke. He rushed from his cabin to find the entire bow engulfed in flames. The Flint’s crew abandoned ship and was quickly rescued by members of the Thunder Bay Island Lifesaving Station.

When the frigid lake water reached the ship’s boilers the ensuing explosion scattered limestone and twisted pieces of metal in all directions and sent the ship to the bottom of Lake Huron.

“Twelve years ago, there were so many gobies on the Oscar it was like buffalos on the plain,” Sobczak said. “As you swam along there were herds of them in front of you. But it’s not like that now.”

In many areas of the Great Lakes, round goby populations have decreased. Round gobies – an invasive species – are now preyed upon by many native species including diving ducks, smallmouth bass, yellow perch, brown trout, walleye and whitefish, according to Minnesota Sea Grant.

“It’s the same with the zebra mussels,” Sobczak said. “We’re not seeing the same numbers. We’re hearing that when divers scrape them off wrecks, they’re not coming back.”

The Indiana (95 feet), Lake Erie

In September 1870, the three-masted sailing vessel Indiana left Buffalo, New York, bound for Cleveland, Ohio, with a load of paving stone. As the ship tacked across Lake Erie, the weather worsened. A sudden squall pounded the ship’s hull and soon the vessel began to take on water.

The captain made a run for Erie, Pennsylvania, but the ship had already taken on too much water. The crew took to the life raft shortly before the ship went down. The waterlogged vessel, heavily loaded with limestone, sank straight to the bottom of Lake Erie.

Emily Anderson works at Diver’s World in Erie, Pennsylvania. She said the Indiana is her favorite deep-water wreck because it’s mostly intact. Video footage of the Indiana, side-scan sonar images and a 3D interactive mosaic of the wreck are viewable on the Regional Science Consortium website.

“We don’t see a lot of fish on the deep wrecks,” Anderson said. “Mostly just burbot.”

But sections of the Indiana are covered with small patches of bright green and pale cream sponge. “Freshwater sponge grows on sturdy submerged objects in clean streams, lakes, and rivers,” according to the National Park Service website.

Freshwater sponges filter food from the water, are highly sensitive to pollution and serve as a food source for a variety of macro-invertebrates including caddisflies, midges and lacewings, the park service website states.

“Underwater structures like shipwrecks support the entire food chain,” Thomas said.

For more of the connections between Great Lakes Now and issues presented in “The Age of Nature,” visit GreatLakesNow.org/Age of Nature or check out our PLAYLIST on our YouTube channel.

Catch more news on diving and shipwrecks on Great Lakes Now:

Diving with Ric: An underwater view of the Lake Huron Middle Island Sinkhole

Big Five Dive: Filming 24 hours of a Great Lakes scuba adventure

“Dream Big”: Diving the five lakes in 24 hours, from the perspective of one of the divers

Eastland Documentary: Filmmakers talk behind-the-scenes journey and stories

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary wreck, William P. Rend (Photo credit: NOAA)