At any given moment about half the world’s population is wearing blue jeans or other denim clothing. And every time we launder our jeans, tiny string-like particles called microfibers come loose, flow out of our washing machines, down sewers and into lakes and oceans.

Now researchers at the University of Toronto say they have found denim microfibers in sediment taken from the Great Lakes. In fact, denim made up 23% of all human-made microfibers in lakes Ontario and Huron. Human-made microfibers include fibers from natural sources such as cotton, and those from synthetic sources such as plastic-based nylon and polyester.

They also found denim made up 12% and 20% of microfibers in sediments taken from shallow suburban lakes near Toronto and in the Canadian Arctic Ocean, respectively.

“We don’t know yet the impacts on wildlife and the environment,” said Sam Athey, who studies sources of microfibers and is one of the study’s authors.

But she and her team are worried: “Even though denim is made of a natural material – cotton – it contains chemicals,” she said.

Concern extend to both natural and synthetic fabrics

Denim is treated with chemicals to improve its durability, which likely means the fibers persist in the environment for a long time.

“We don’t know exactly what chemicals. That’s proprietary information and it’s hard to know because different chemicals are used for different processes,” said Athey.

We know a bit more about the synthetic indigo dye used to give jeans their distinctive blue colour. Indigo dye used to come from the leaves of certain plants that grow in the tropics, but these days most jeans are dyed with synthetic indigo. Some of the chemicals used to process the dye, such as formaldehyde, are toxic.

Athey and her team found microfibers from other fabrics too, but they chose to focus on denim because about half of the human-made “natural” fibers they found were from denim. She said the team’s next step is to assess their possible impact.

The University of Toronto study is important because so far, most of the concern around the potential dangers of microfibers has been focused on plastic-based fabrics such as nylon and polyester, said Laura Markley, who studies plastic pollution in freshwater systems at New York state’s Syracuse University.

There is good reason to be concerned about plastic fabrics. They’re oil-based and made from many different chemicals, such as polyvinyl chloride which is carcinogenic and phthalates which disrupt our hormones.

But chemically treated natural microfibers such as denim are just as common, if not more, says Markley. That may be partly a result of consumers trying to do the right thing by switching from nylon and polyester to natural fabrics – cotton, hemp and bamboo for example – without understanding that chemical treatments for these fabrics can also be harmful.

“People want a clear-cut answer about what to buy,” said Markley. “If I buy only natural fibers, will that be better? Well, not necessarily.”

That comes as no surprise to those who study the fashion industry, which is the second most polluting industry in the world after oil, according to the United Nation. The UN singles out denim for its water-hogging ways, pointing out that it takes around 7,500 litres of water to make a single pair of jeans. That’s equivalent to the amount of water the average person drinks in seven years.

Still, some manufacturers are trying to clean up their act, including making fabric from fungi. And materials researchers at the National Research Council of Italy – a country known for its fashion industry – are trying to create environmentally friendly coatings that reduce microfiber shedding.

Materials scientist Francesca De Falco is a part of a team at the research council that recently developed a coating made from pectin, a carbohydrate found in the cell walls of plants. While it’s still in the experimental stage, they found nylon fabric treated with the pectin coating shed 87% fewer microfibers than non-treated nylon.

“We’re doing more tests to see its viability over many washes and we want to see if it can be applied to polyester,” said De Falco.

In the meantime, she recommends buying just a few well-made pieces of clothing that will last a long time and washing them less often.

Athey agrees. She said she grew up thinking she had to wash her jeans after every couple wears but recently discovered that most jeans companies recommend washing them once a month.

As part of their study, Athey and her team laundered used jeans and discovered they shed about 50,000 microfibers per wash. While wastewater treatment plants capture anywhere from 83 to 99% of microfibers, they do so by letting the fibers settle into the sewage sludge that accumulates at the bottom of treatment pools. This sludge often ends up as fertilizer on agricultural fields and runs off into local waterways when it rains.

“So these fibers may just end up entering the environment another way,” said Athey.

A potential solution for keeping both natural and plastic microfibers out of our lakes is to install a washing machine filter. Athey’s colleague, Lisa Erdle is currently testing filters in the town of Parry Sound, Ontario, on the shores of Georgian Bay. Lab-based research suggests the washing machine filters remove roughly 90% of microfibers.

Read more about plastics and fiber pollution in the Great Lakes on Great Lakes Now:

Plastic Permanence: Research shows plastic becoming part of Great Lakes lakebed

Chemical Hitchhikers: Great Lakes microplastics may increase risk of PFAS contaminants in food web

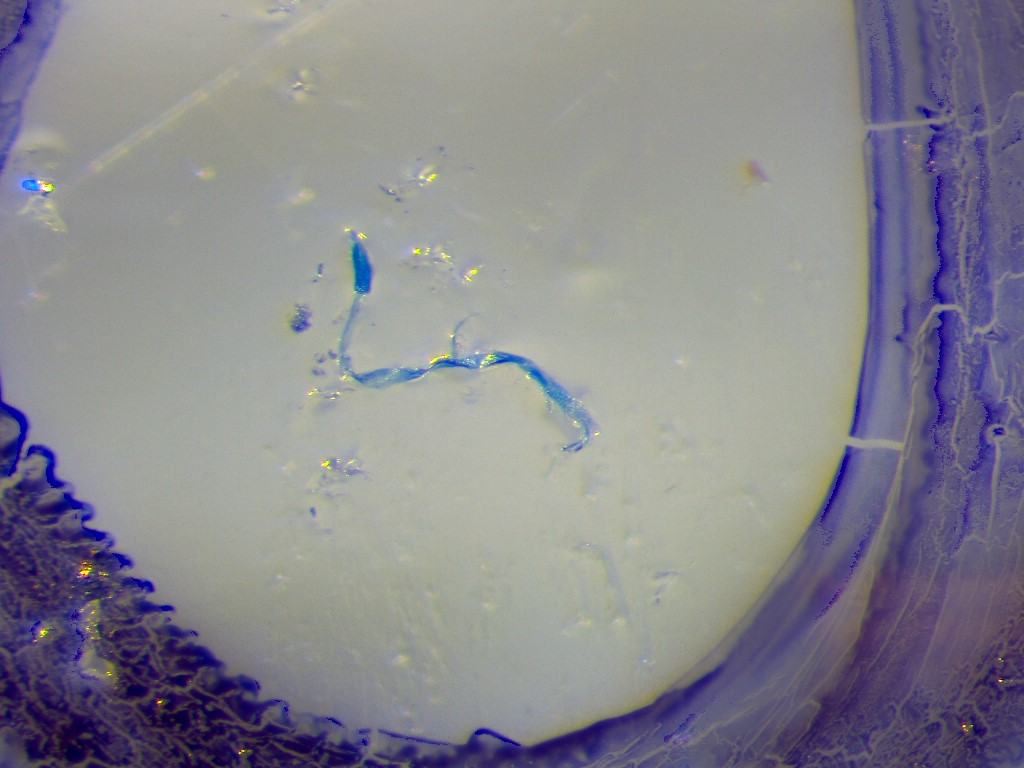

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: This image, taken with a high-powered microscope, shows the distinctive twisted string-like shape of a cotton microfiber. Its indigo blue color means it comes from denim. This fiber was collected from wastewater discharged into Lake Ontario. (Photo credit: Sam Athey)