By Kimberly M. S. Cartier, Eos

This story originally appeared in Eos and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

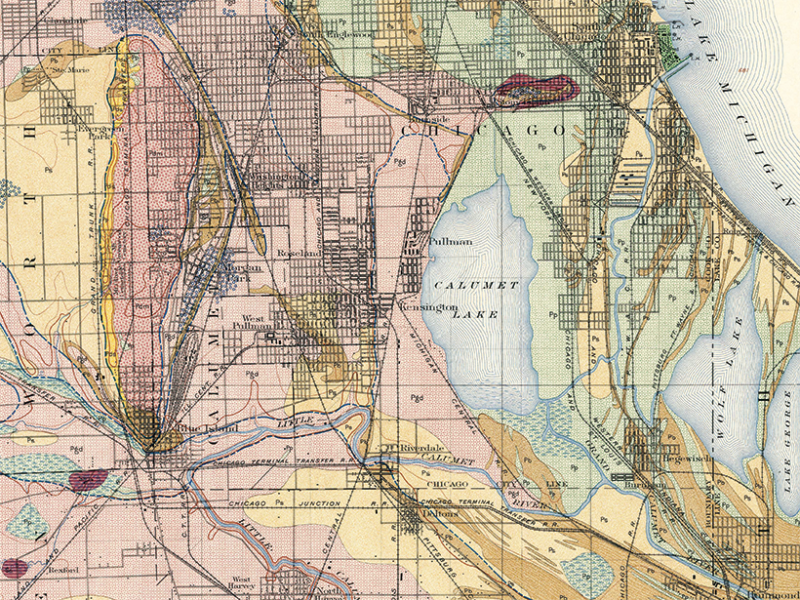

As Chicago’s industries and population boomed in the late 1800s, city officials decided to reverse the course of the Chicago River so that it flowed away from Lake Michigan. The river’s reversal in 1900 carried industrial pollution away from population centers and increased shipping opportunities from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River. It also began draining the extensive network of wetlands that had covered most of the Chicago area after the last ice age. Industrial and residential developments further altered the wetlands’ reach.

All told, Cook County, Ill., which encompasses Chicago, has lost 40% of its wetland area from the time of the reversal to today, according to research published in Urban Ecosystems in May. Wetlands such as rivers, streams, marshes, swamps and lakes remove pollutants, manage groundwater, cycle nutrient and support biodiversity comparable to tropical forests and coral reefs.

“Wetlands are not only the kidneys of the region, absorbing and cleaning a whole lot of water, but they are vital habitats for many birds and insects,” said Iza Redlinski, a conservation ecologist at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History who was not involved with this research. “Monitoring wetlands and other habitats is important to know how we’re progressing and what actions can be undertaken to preserve them both on the large and small scale.”

Draining Swamps to Make Lakes Instead

The researchers analyzed historical and modern maps of Cook County. They counted the number and types of distinct wetland features and measured the individual and total area covered by wetlands.

They found that from the historic period (1890–1910) to the modern period (1997–2017), the total area of Cook County wetlands shrank from 73 to 44 square kilometers (–40%). The number of wetland locations increased roughly tenfold over that time, but the average size of each location is about 10 times smaller today than it was in 1900. This shrinkage was led by the conversion of sprawling marshes to small lakes and retention ponds, said lead author Joey Pasterski, a graduate student in Earth and environmental sciences at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). Overall, the region lost 85% of its swamp and marsh area during the 20th century, the team found.

“The thing that struck me the most was how clear the connection was between what was wetland and what now is lake,” Pasterski said. When walking or biking around the city, he added, it’s easy to notice a small isolated lake here and there, but the research revealed how widespread the phenomenon is across Cook County. “When you look at the map, it’s unmistakable.”

“This whole area was wetlands” that have since been transformed by human development, Pasterski said. “Now every time it rains and the park outside my house floods, I reflect on the idea that, yeah, it should flood. It should always be flooded.”

“We’ve changed the hydrology of the entire area, and that’s going to be true of any city,” especially in the wetland-rich Midwest, said coauthor and UIC paleontologist Roy Plotnick. “The connectivity of the landscape has changed significantly as a result of [metropolitan expansion], and that’s something that needs to be thought about going forward as we think about conservation and restoration of the land.”

“Intact wetlands are of critical importance for native wildlife in general,” said Field Museum conservation ecologist Mark Johnston, who was not involved with this project. “When protected in urban areas, they can also serve as connective corridors which are super important in fragmented landscapes, particularly with the increased pressures of climate change.”

Native Biodiversity Lost

Both the loss of total wetland area and the transition from swamps to lakes affected Cook County’s wetland-reliant species. The team gathered information on historic and modern species of mollusks, fishes, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals by scouring publicly available resources like museum collections, online databases and catalogs, and even apps used by wildlife spotting communities.

The researchers found that wetland-reliant reptiles, amphibians, and mammals experienced little to no biodiversity loss during the 20th century. Mollusk species, however, changed significantly: Of the 107 native mollusk species present 100 years ago, 53 remain today, and 26 nonnative mollusk species were introduced into wetland habitats intentionally or accidentally. And although the numbers of fish and bird species have increased over time, the increased biodiversity is largely due to nonnative species replacing native ones. Some of the nonnative species, like silver carp, have been deemed invasive and injurious to local ecosystems.

This research will aid conservationists, Redlinski said, and can also help developers plan projects that have minimal impact on the remaining wetland ecology. “Knowing what species have disappeared or which ones are on the decline can allow managers to either prepare sites for reintroductions, if that is possible, or to adjust the site in such a way to allow for that organism’s life cycle to be completed,” for example, keeping the land wet long enough for native frogs to complete all the stages of development.

This research was conducted by graduate students enrolled in a course on species extinction taught by Plotnick, developed out of a class project, and relied solely on freely available public resources. The graduate researchers have moved on to other projects since the course ended last spring, but Pasterski hoped similar projects will spring up in other metropolitan areas.

“The fact that we were able to do this as a class project using just resources from the city that were free…to me reflects the ability for this study to be repeated in other areas as well using similar resources,” he said. “Anywhere you have a museum collection over 100-year time span or more you can do a similar study in the classroom in the span of a year.”

Read more news on Great Lakes Now:

Want the Youth Vote? Prioritize Climate Change

In Perpetuity: Toxic Great Lakes sites will require attention for generations to come

Across the U.S., millions of people are drinking unsafe water. How can we fix that?

Total Maximum Daily Load: Court case looks to push for Ohio EPA nutrients limit for Lake Erie

Bringing Back Milwaukee’s Swamps: Part I

IJNR Snapshots: Some Ohio farmland is being returned to its glory days as the Great Black Swamp

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: The Calumet Quadrangle boasted extensive wetland areas in 1902 as Chicago faced rapid industrial expansion. (Image credit: USGS/Alden, W.C.)