The teenagers and scientists searching for the 2017 meteorite in Lake Michigan found more than they had been looking for, representatives from the team reported yesterday.

In a live update on the Adler Planetarium’s YouTube channel, students and researchers shared two major finds from The Aquarius Project’s years-long attempt to find the meteorite: a sample that could be from that meteorite and a sample from a meteorite much, much older.

The Aquarius Project came about after a meteorite lit up the night sky before crashing into Lake Michigan off the Wisconsin shoreline in February 2017. It made the news and caught the attention of Chris Bresky, the teen programs manager at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. He saw an opportunity to enlist teenagers in the hunt for the sunken meteorite.

Great Lakes Now reported on the search last year in this segment:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.The teenagers involved in the project designed, built, tested and deployed an underwater meteorite recovery sled under the mentorship of scientists and researchers from NASA, Shedd Aquarium, Field Museum of Natural History and Adler Planetarium. The sled, named Starfall, has been sent trawling Lake Michigan for meteorite fragments in the summers since.

Bresky, Adler Director of Astronomy Geza Gyuk, NASA scientist Marc Fries and three of the teens involved in the project – Jack Morgan, Jarred Scales and Rome Jones – went live on YouTube to talk about the project, the process and their findings.

“It’s amazing that after all this work we’ve finally found something,” Morgan said.

Over the course of the project, the teens and their mentors innovated a number of tools and equipment to find the meteorite. Much of the work involved high-powered magnets because they were looking for “little melted pieces of rock basically,” according to Fries. That’s where an unexpected difficulty cropped up.

NASA scientist Marc Fries explains the process of sifting through what they found on Lake Michigan’s lake bed while looking for meteorite fragments, during a Sept. 10, 2020, livestream.

“It turns out this site where they collected material is terrible for looking for this material because it has a large volume of material from the steel-working industry,” Fries said. “Maybe it was slag that was dumped in the lake or washed out in the rivers or it’s from a shipwreck nearby. We don’t know, but one way or another there’s an awful lot of what’s called slag, the melted remnants of making steel and iron, and it’s in there.”

Despite that, the team still managed to find likely meteorite fragments.

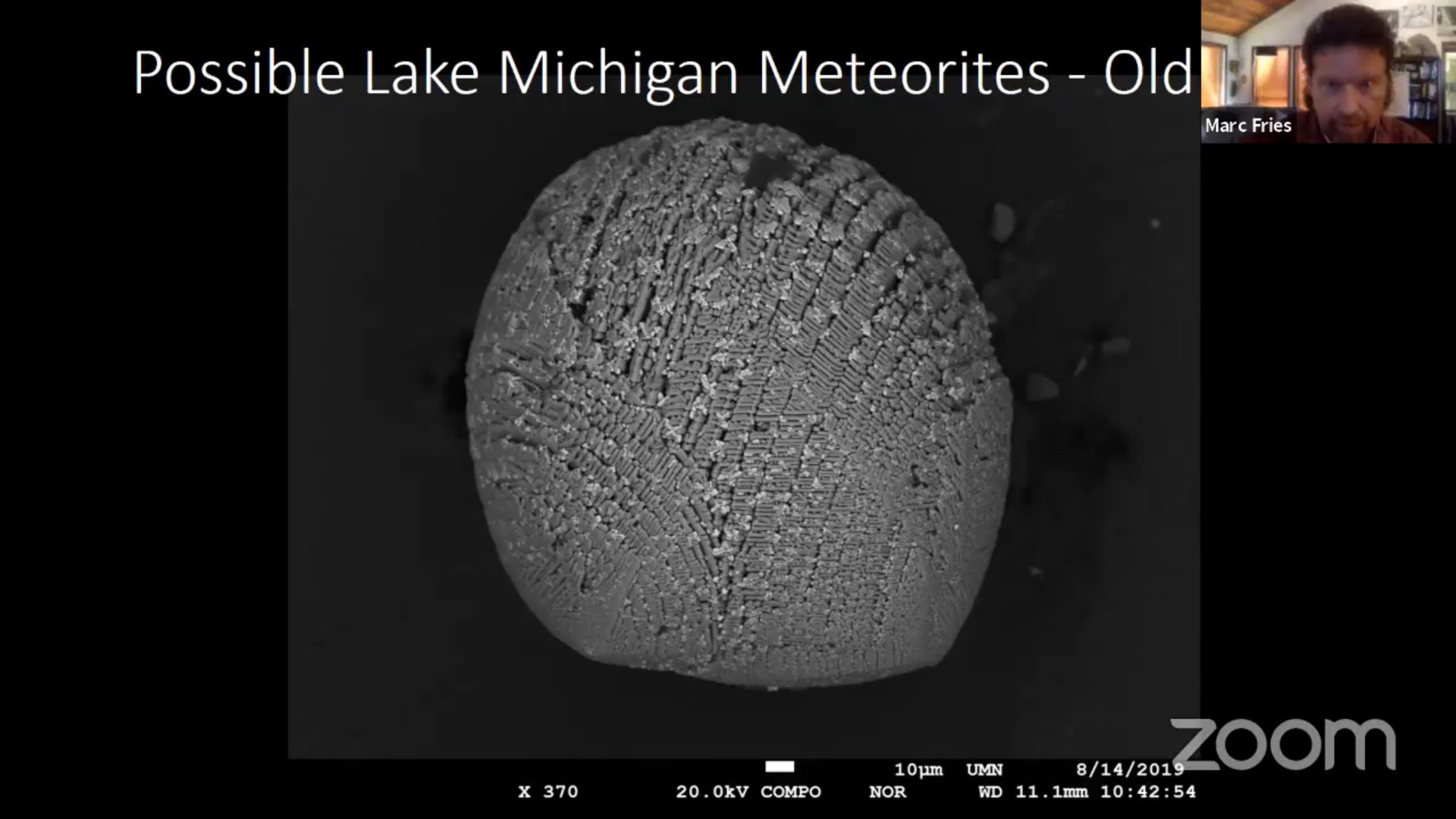

One sample was a smooth sphere, but that type of shape usually takes a long time to form, according to Fries.

NASA scientist Marc Fries talks about one of the possible meteorite samples found by The Aquarius Project, during a Sept. 10, 2020, livestream. (Image courtesy of Scott Peterson)

“I don’t think that this could have happened in just the time between now and 2017,” Fries said. “I’d be comfortable saying this is probably a micrometeorite but it’s probably much older than the (2017) meteorite fall.”

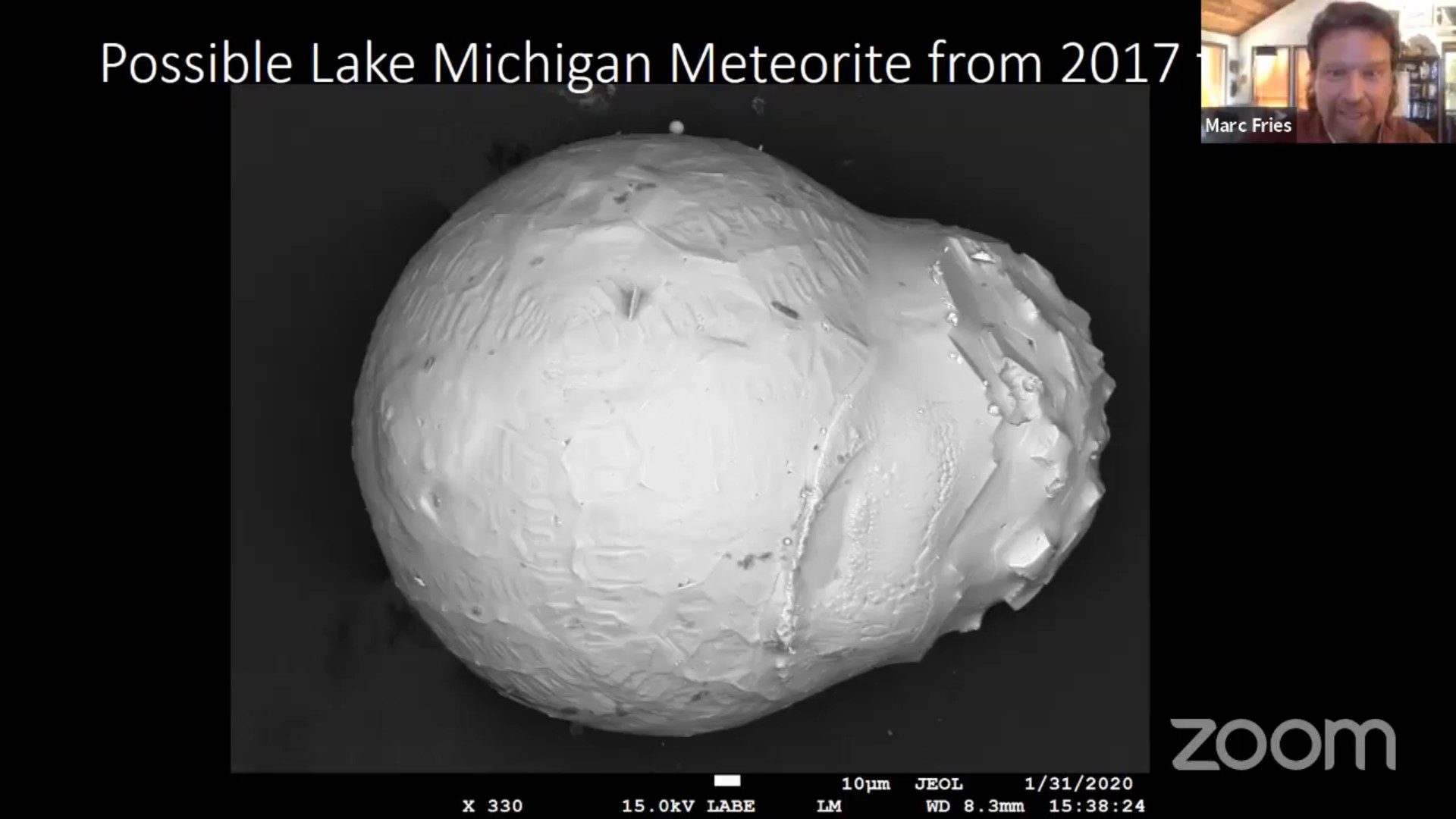

The other sample shared during the live update was shaped somewhat like a droplet.

“That’s pretty typical for material shed from a meteorite fall or some micrometeorites even,” Fries said.

It has exposed nuggets of nickel, which is “one of the hallmarks we look for, for material from outer space,” according to Fries.

NASA scientist Marc Fries talks about one of the possible meteorite samples found by The Aquarius Project, during a Sept. 10, 2020, livestream.

“If you look at the thing overall, you can see this is not corroded, this is not etched, this doesn’t have rust coming off it, there’s no evaporite,” Fries said. “It looks fresh. So a combination of chemical composition that looks consistent with meteorite infall and just a general fresh, new-looking nature of this particular particle – I think this is the best candidate so far for material from that meteorite fall. There’s more we can do to test it, but this is quite promising.”

The findings were announced to the teens just this week, so the excitement was fresh on their minds and in their voices as they shared their reactions.

“It’s crazy because it’s such a big area for us to get, and the things we were getting were so tiny,” Jones said. “When we went on the trip there were these huge gallon buckets, and I never thought we’d find them because it’s huge, there’s so much material. The fact that we actually found it is just crazy.”

Aside from the meteorite fragments, the team found the lakebed covered in quagga mussels, an invasive species that started plaguing the Great Lakes in the late 1980s.

This isn’t the end of the project either. There’s still three containers worth of material to sort through, according to Bresky.

“The future of the project, especially with COVID, is more up in the air,” he said.

Adler Aquarium also is looking to apply the model of this project to new topics and new experiments, including one on light pollution and urban night sky areas.

“This far exceeded our expectations,” Bresky said. “It’s reinforced the innovative power of young people and also, I think, inspired people in the field.”

Check out more meteorite content on Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes Meteorites: From 450 million years ago to now

Fleeting Fireball: Students comb Lake Michigan for deep space remnants

Missing Meteorite: Did the search in Lake Michigan find it?

Featured image: A probable ablation spherule micrometeorite that NASA scientist Marc Fries believes has a good chance of being from the 2017 meteorite fall. (Photo courtesy of Adler Planetarium)

1 Comment

-

Thanks