As Ohio farmers in Lake Erie’s Western Basin watershed face declining crop prices, increased media scrutiny and the looming threat of stricter regulations on the industry’s use and release of nutrients which cause algal blooms in the lake and its tributaries, they are in a constant battle to reduce their footprint on the lake and to stay in business.

Bill Myers, 58, has been farming his entire life and currently grows crops with his wife, two sons and a brother on a 2,000-acre Lucas County spread the family has been tending for five generations, since 1896. He said media attention northwest Ohio farmers have received in recent years isn’t exactly unfair, because there is most definitely a problem. But farmers are working on it, he said, and spending plenty of money in the process.

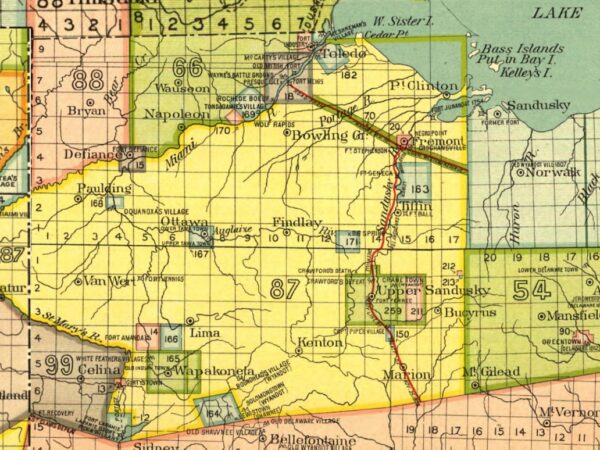

Myers Farms operates on 2,000 acres near Maumee Bay on Lake Erie. (Photo credit: James Proffitt)

“The thought that comes to mind is there’s a disconnect between the farmer and the consumer, the understanding about how agriculture works,” he explained. “We’re so far removed from the mainstream of normal, people don’t truly understand the process that changes or the evolution of what we’re doing, what that actually takes.”

Myers contrasted a typical auto plant, which changes presses and operations for new models in just weeks, with farming, which he described as a constantly evolving process.

“With a changeover in a month, the presses change and ‘Boom! We’re going to start producing these things tomorrow,’” he said. “Agriculture just doesn’t work that way. When you’re interacting with the environment there are so many changes to our weather and the ramifications of what that does affects things we do either negatively or positively. A lot of times we don’t know it’s happened until 10 years later.”

Myers said recent changes in weather patterns have made farming more unpredictable and expensive.

Myers cited “100-year” rainfalls that seem to be happening every two years as one example.

“They are definitely a challenge, though they’d be a challenge to the environment even if you and I weren’t here,” he said.

Watch Great Lakes Now’s segment on Ohio farms and Lake Erie’s algal blooms:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Step one, soil testing

Two culprits often identified as contributors to algal blooms are nutrients washed into waterways from animal manure and from commercial fertilizer. While Myers Farms utilizes both, its manure use is limited.

“My son has about 15 or 16 head of cattle,” Myers explained. “So we use the dry manure. We’ll plant wheat and then when we harvest our wheat, when it’s super dry, we’ll look at our soil tests and see which area is in absolute need, the most dire, of phosphorous and we’ll usually spread it there and work it in. From our standpoint, it’s an added cost.”

According to Myers, the farm’s use of soil testing is paramount to conservation. But it’s something necessary to modern farming, unlike farming during generations past.

“In the old days way, way back when I was eight years old there was no soil testing. You just spread the manure from the animals you had on the fields and that’s how you recycled your nutrients,” Myers said. “I think it was around the mid-70s they came up with the fertilizer recommendations and all the advances in agriculture prompted soil testing, which was kind of in its infancy then.”

Soil testing, at least for Myers Farms, is performed for both environmental concerns and possible cost savings.

“If you have an aggressive soil testing process, in the end you may not save money, but because you’re applying fertilizer only where you need it and not where you don’t, you’re increasing yield. You could save money on fertilizer or make more money on yield. Either way, there’s a chance it will benefit the farmer.”

Soil testing, which involves taking physical soil samples which are then lab-tested, are often conducted by fertilizer retailers. Most labs charge between $7 and $10 for a basic test that typically includes analyses for pH, available phosphorus, nitrogen, potassium, calcium, magnesium and organic matter.

“A traditional soil test is generally one test per 20 acres, so you’d be looking at five tests on 100 acres,” said Mike Libben, district program administrator for the Ottawa Soil and Water Conservation District. “Now, most ag retailers that do soil sampling do it site-specific, GIS (geographic information system.) They might be pulling a sample for every soil type in the field or every two or three acres, so you’d get a lot more samples pulled and you get a lot more accurate diagnosis of what the field is.”

Libben said recommendations by retailers can mean cost savings on commercial fertilizer purchases by reducing usage where it’s not needed.

“Every three years is recommended,” he said. “We really encourage people to do it that way because it’s site-specific.”

Paying for soil-testing is simple, and getting commercial fertilizer spread at variable rates is simple, too. But it’s not free. Commercial fertilizer operators often apply fertilizer they sell.

Myers said smaller farmers often rely on hi-tech equipment operated by agriculture cooperatives. The price for equipment can vary widely, sometimes reaching toward $250,000. Ag cooperatives purchase the pricey equipment, which members may access without a huge investment.

“Once you reach an economy of scale, you can usually begin purchasing the stuff yourself. Prior to that, if you’re too small to absorb that expense, which could be $20,000, $40,000 or $100,000 or more, your co-op is usually set up to absorb those costs. They’ll take the hit then spread it over tens of thousands of acres.”

Myers said the average farmer could spend between $15 and $20 an acre for the latest, GIS-based applications systems, which adjust fertilizer rates automatically based on soil tests and hyper-exact location information provided by satellites.

“If you farm 2,000 acres, $20 an acre becomes $40,000 a year.” Myers said. “In three years I can buy all the equipment myself, do it myself and 10 years down the road I’m way ahead compared to hiring them to do it. With a co-op at least, you can access that technology and see the result before the expenditure.”

While fertilizer application using the newest systems is one conservation practice farmers use, a few simple techniques have been around for decades, though still bear an added cost.

Ohio farm (Great Lakes Now Episode 1016)

Filter strips regulations are outdated

A vegetation buffer between crops and streams, ditches, ponds or other waterways is a highly recommended best management practice. Ideally, a gently sloped buffer strip will host vegetation that slows soil loss from fields and traps agricultural nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous before they enter the water.

Filter strips are generally at least 20 feet or more in width and are most often planted with perennial grasses. This vegetation retains and utilizes portions of phosphorous and other nutrients before they can reach waterways.

Myers said buffer strips are especially helpful during severe weather events, like the ones he said are happening more often. But many government-funded conservation programs which subsidize buffer strips may miss the mark, he said.

“The filter strip is the same as an oil filter in your car, it’s designed to remove something you don’t want. On our cars we take off the old filter and throw it away and put a new one on,” he said. “This has always been my complaint, that ‘We’re going to pay you to install this strip but you can’t touch it you have to leave it alone.’”

Myers said he believes rules regarding buffer strips which were written roughly 40 years ago should be revised.

“They’re often geared toward soil conservation and erosion, because we don’t want soil with the nutrients washing into ditches, that’s the way they were written,” he explained. “But the problem now is that dissolved reactive phosphorous has become the culprit and that’s the one you need to capture and remove. You need to keep that sink well not empty, but not overflowing, so it can do the best it can at retaining and removing the nutrients.”

That could be achieved by the occasional harvesting or grazing of the crops, he said, which is most often prohibited on subsidized installations.

Programs are available to farmers interested in utilizing BMPs, especially those in critical areas where water quality is of high concern. But many of those programs prohibit the harvest or grazing of buffer strips. Most farmers never receive any money from U.S. Department of Agriculture Conservation Reserve Programs. The programs require an application process and environmental impact assessments to determine which sites would prove most beneficial.

“There are competitive programs where you hope to get some funding. There are many different grants, but it always depends on how much funding is available,” Libben said. “It’s kind of a misnomer that there’s all kinds of money available and that a farmer can get some anytime he or she wants.”

Libben said farmers interested in the subsidies must show interest and request the assistance. Criteria set by the U.S. Department of Agriculture often determine who may receive assistance during any given season. The cost to farmers utilizing buffer strips includes the seeds, sowing and maintenance.

The cost of buffer strips varies farm to farm with yields and crop prices. A 30-foot buffer strip 1,400 feet in length takes about an acre out of production. For corn in the Midwest, that’s between $540 and $890 in lost cash crop revenue and for soybeans between $490 and $640.

Ohio farm (Great Lakes Now Episode 1016)

Cover crops are popular and effective

Planting a secondary crop, either after harvest or while cash crops are still growing, is a popular method for both controlling soil erosion and keeping nutrients in fields. Cover crops, like buffer strips, also help trap phosphorous and nitrogen, keeping it out of ditches, then streams and eventually Lake Erie and the other Great Lakes.

“Any time you have anything growing in soil it’s pulling nutrients out of the soil and recycling them back and helping microbes grow,” Libben said. “It’s also been shown that cover crops reduce nitrogen losses, which when it comes to Lake Erie and algae blooms, phosphorous makes it grow and nitrogen can make it more toxic. That’s the basics of what we’ve heard. The cover crops will use the nitrogen, store it and then as they die off, return the nitrogen for use by the cash crop that’s planted next season.”

Seth Rockafellow, a sales rep with Farmer’s Business Network, said there are numerous avenues for keeping fields covered including various beets, radishes, turnips, kale, rye and clover, among others. And some can be used to graze cattle or harvest and bale for feed. But not so for those receiving subsidies through most conservation programs, since rules governing these practices restrict their harvest. The price of seed varies.

“Typically it’s sold either by the pound or the 50-pound bag,” he said. “You’re looking probably 75 cents to $2 a pound, depending on what kind of mix you’re looking at.”

Rockafellow said the average seed required runs about 15 pounds per acre.

“In the spring you can just till them up and plant right into them,” he said.

Wisconsin farms operate under strict rules

“I would say that in Wisconsin we are probably as stringent if not more than Ohio,” said Eric Cooley, co-director of Discovery Farms Wisconsin. “We have extremely strict rules that farmers are mandated to follow.”

According to Cooley, growers in the state operate under rules set forth by the state for each specific soil type in which their farm is located.

“SNAP (Soil Nutrient Application Planner) plans take into account soil loss, so farmers are only allowed to do certain crop rotations based on their soil types and a number of other factors. They’re very strict in Wisconsin with the regulatory process,” he said.

And in Wisconsin, row crow farms must follow the same rules as dairies or concentrated animal feeding operations, he said.

“That’s one of the things that’s really challenging for those that are doing row crops, especially on some of our heavier clay soils in our Lake Michigan basin,” Cooley said. “It’s really soil-driven.”

Farmers in the Lake Michigan watershed have heavier clay soil, which presents problems with surface runoff. Pinning down a statewide number for cover crop costs to farms would be difficult, Cooley said, since conservation practices vary widely by region. Somewhere between $10 to $20 an acre would be close to what Wisconsin farmers spend planting cover crops to help keep nutrients out of waterways.

“That’s for a simplistic mix,” he said. “Or it could be $80 an acre if you’re going to do a wildlife species mix, it could be varied.”

Like Ohio, Wisconsin offers programs to conservation-minded farmers. One such program includes watershed grants, which a group of farmers may receive.

“To qualify, there must be five farmers (or more) in the watershed who want to conduct conservation improvement activities,” said Leanne Duwe, public information officer with the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection.

But grants aren’t just handed out freely. According to Duwe, the group must work with her office, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, county conservation agencies, Discovery Farms and the University of Wisconsin to create a plan.

“We provide cost-sharing for some conservation practices intended to cover 70 percent of costs,” she said. “Costs of implementation vary by operation, size vendor and location.”

Ohio farm (Great Lakes Now Episode 1016)

Conservation expenditures often ideological

Bill Myers said, utilizing all BMPs, his farm easily spends $55 to $60 an acre each year. On a 2,000 acre farm, that’s more than $100,000. And, he added, it doesn’t pay for itself in financial terms. At all. He compared it to homeowners insurance, where few claims are filed. But the claims that are filed can be big.

“Why do we buy insurance for our cars? My father went his whole life and was never in an accident. What a waste of all that money,” he said.

BMPs are no different, according to Myers: they’re an insurance policy.

“The relativity is clear: you’re putting these practices to work in case of a runoff event happening so that you can mitigate it the very best that you can. It’s no different than insurance. It’s just a cost. You’re trying to help mitigate the impact to the environment to benefit all.”

Incorporating or injecting fertilizer into the soil, instead of broadcasting it on top, is expensive. Implements used to place fertilizer can run upwards of $100,000. Computer software that determines how much fertilizer goes where? Add another $25,000 or so, Myers said.

Farmers who raise enough livestock to produce large amounts of nutrients and who also plant row crops must also spend significant sums on implements used to store, move and apply manure.

Utilizing manure as fertilizer can be implement-intensive, according to Mick Zoske, of Zoske Manufacturing, in Iowa Falls.

“Depending on the row unit they can run from $1,500 to $2,400 each, and this does not include everything else required,” he said. “If a person has an applicator tank that can only broadcast on top, they’re looking at a minimum of $20,000 to add everything required. A lot of these setups run over $30,000 to add to a tank. If a person uses a drag hose system, the toolbars can run up to a little over $200,000 set up with row units to inject the manure.”

Younger farmers leaning toward conservation

“I would say as a general rule, younger farmers are into it,” Myers said. “My father later in his life was more active in trying to be a conservationist than he was in his younger years. From the stories I hear.”

Myers said that while age brings wisdom, it also brings money.

“I think as we get older and closer to meeting our Maker, we get a little more conscientious about the things we do. That being said, as the new generation comes out of education systems where they’re subjected to the up-and-coming thing, I think they probably bring ideas to the older generation,” he said. “And the older generation actually has the financial ability to make it happen. I think it’s a blending of those two generations that actually gets the best results.”

Read more on Great Lakes agriculture and algal blooms on Great Lakes Now:

Muddied Waters: Bureaucratic process leaves well water at risk and farmers feeling targeted

Factory farms provide abundant food, but environment suffers

Water and Wonder: Great Lakes Now producer talks the lakes and his work covering them

Toxic Algae 2020: Moderate bloom forecasted for Lake Erie

Featured image: One of Myers Farms’ soybean fields. Myers operators say they do everything in their power to raise crops responsibly and help protect Lake Erie. (Photo credit: James Proffitt)

1 Comment

-

What about plowing across the direction of runoff? Should not cost any money, just knowledge of your topology with respect to river or lake.