This is the second in a three-part series that will explore the history of Lake Superior and the Boundary waters, the communities affected by two proposed copper mines, the arguments in favor and against the mines, and what the mines might mean for the future of the Great Lakes. Read the first part here and third part here.

Just a few hundred years ago, the land that would become Minnesota was filled with rivers, wetlands and wild rice, or manoomin, as it’s called by the Ojibwe. A staple food and critical component of cultural and religious practices, wild rice thrived across the region.

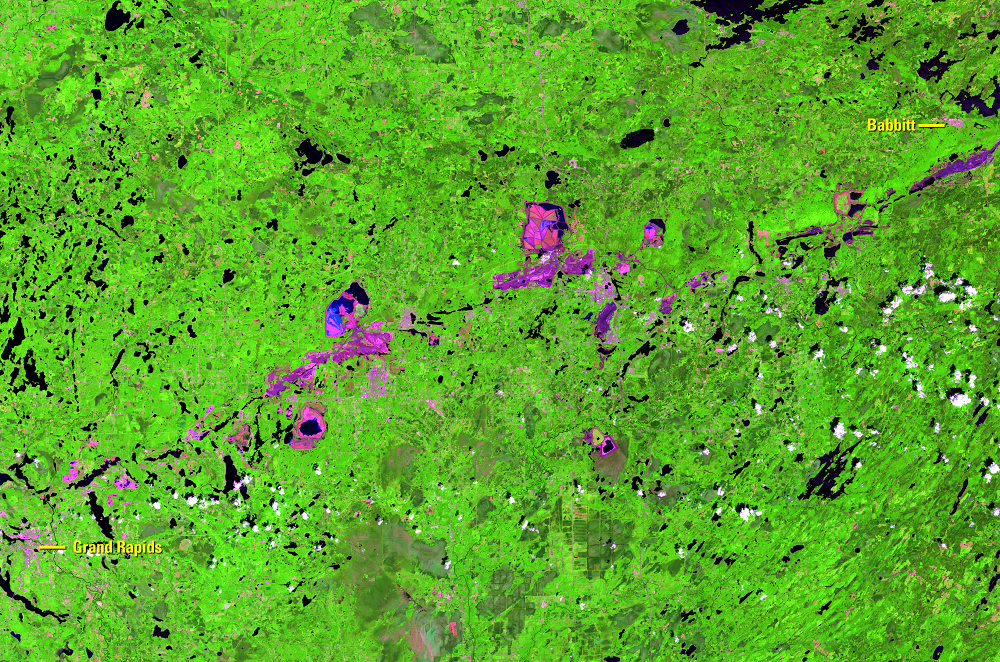

Today, the scars of mining sites across the Minnesota Iron Range are visible from satellites in space. The invisible legacy of those mines is equally pernicious. From fish loaded with mercury to wild rice beds killed by an overdose of sulfates, the impact to the environment has been incalculable.

As PolyMet’s proposed copper mine, NorthMet, has moved forward, tribal communities and environmental advocacy groups who have long grappled with the problems caused by taconite mining are now arguing vociferously against a copper-nickel project that could be even more damaging.

Despite efforts by these groups, PolyMet was on the brink of moving forward at the beginning of 2020. More than a decade of environmental impact studies and permit applications had resulted in the project nearing full approval. But in the past six months, the Minnesota Court of Appeals has sent back four permits for review: two dam safety permits, a permit to mine and an air emissions permit. The court has also been scrutinizing a water discharge permit as well. Now the company is mired in litigation, waiting for the Minnesota Supreme Court to issue a ruling that will either let them move forward or force them to participate in further hearings over the feasibility of their project. The outcome of the cases could have major repercussions for the future of copper-nickel mining throughout the state.

From environmental studies to court cases

The first thing Nancy Schuldt wants to be sure people understand is that getting the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa involved in lawsuits against PolyMet was never the goal.

“Lord knows I have written hundreds if not thousands of pages of comments over the course of the PolyMet review process,” Schuldt said. “We raised issues, we provided data, we provided our own analyses, science-based and independent. And we were totally blown off at every juncture. So we were left with the only recourse.”

Having worked for the Band for more than 20 years, Schuldt is an expert on water management issues and had to become adept at navigating the intricacies of copper-nickel mining.

PolyMet Mining, a Toronto-based company owned by Switzerland mining conglomerate Glencore, began the environmental review process in 2004. The next year, the company took ownership of an ore processing plant in northeastern Minnesota, formerly owned by LTV Mining Company and used for taconite. The site proposed for the project comprises approximately 19,000 acres spread across the headwaters of the St. Louis River near the towns of Babbitt and Hoyt Lakes. The NorthMet mine has been projected to produce 72 million pounds of copper, 15.4 million pounds of nickel and 720,000 pounds of cobalt each year of its operation, despite less than 1 percent of the ore being marketable mineral. With a proposed lifespan of 20 years and a projected 360 jobs being directly created by the mine operations, the company predicted the mine would generate $515 million each year.

The main features of the proposed mine include an open pit sulfide-ore copper-nickel mine; a transportation line to carry ore to a processing facility several miles away; and a tailings basin to hold the leftover processed ore.

Throughout the environmental review and permitting processes, which have lasted more than a decade, tribal communities and environmental groups have objected to PolyMet’s assurances that its technology will prevent environmental degradation

In 2011, the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa provided PolyMet with a review of the cultural and traditional religious significance of areas within the NorthMet project area. One of the authors summarized Band members’ unease over the mine, writing, “The area still supports cranberries, blueberries and trees with barks that was (and still is) used for illness. In addition, the pristine waters, fish, and natural habitat for fur bearing animals and birds will be affected by the mine. Our thoughts are on the generations to come and the generation that is here now.”

In September 2013, the Tribal Cooperating Agencies submitted their own cumulative effects analysis, pointing out their many concerns over the proposed mine.

“The Fond du Lac, Bois Forte, and Grand Portage Bands, as well as the 1854 Treaty Authority (1854) and the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), have consistently advocated for a more robust, comprehensive CEA for the PolyMet NorthMet project and other mining projects,” the groups wrote. “We have observed that current, historic, and ‘reasonably foreseeable’ mining activities have profoundly and, in many cases permanently, degraded vast areas of forests, wetlands, air and water resources, wildlife habitat, cultural sites and other critical treaty-protected resources within the 1854 Ceded Territory.”

This ceded territory was signed over to the United States through a treaty with the Ojibwe in 1854. The treaty established permanent reservations for the Fond du Lac, Grand Portage and Bois Forte Bands, and granted tribal members the rights to fish, hunt and gather on the ceded land. (The Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission published a full review of Ojibwe treaty rights for bands across the Great Lakes region here.)

And in January 2016, as the proposed mine moved forward and 6,650 acres of Superior National Forest were prepared for a land exchange with PolyMet, GLIFWC once again submitted a statement arguing that the company’s final environmental impact statement failed to address concerns that had been raised by tribal communities and GLIFWC’s own environmental assessments. In their comments, GLIFWC noted the final EIS was “scientifically indefensible in several areas,” such as the report’s characterization of mercury impacts, its characterization of the site’s hydrology and its conclusions about how it will meet water quality standards.

A study commissioned separately by the Fond du Lac Band found the St. Louis River watershed provides an estimated $5 billion to $14 billion in ecosystem services each year, from food resources to flood prevention.

“The EPA understood that the band was legitimately concerned that the destruction of 1,000 acres of wetland in the headwaters area of the St. Louis River could increase methylmercury in the St. Louis River watershed, which is already highly impaired for mercury,” Schuldt said. “It is not permittable under Clean Water Act to permit a new action that would cause or contribute to an existing impairment.”

Despite these objections, PolyMet received permits from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Watch Great Lakes Now‘s segment on Minnesota mining here:

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Environmental groups engaged with lawsuits as well

When Paula Maccabee got involved with the PolyMet project in 2009, she said there was already “a lot of understanding of the importance of protecting the Boundary Waters and really no investment of resources, timing, organizing and advocacy in protecting the Lake Superior watershed. We realized that the first proposed mine was taking advantage of that gap.”

As advocacy director and counsel for the nonprofit WaterLegacy, Maccabee immediately jumped into the fray.

At first, WaterLegacy filed a federal case to stop the land exchange that would allow PolyMet to dig on public lands that were part of Superior National Forest, arguing that the state undervalued the land being given to the mining company. When the exchange moved forward all the same, WaterLegacy began looking at the permitting process. Through records requests, they found that the EPA had serious concerns about the water permit. A leaked email later revealed that a Minnesota regulator asked EPA staff not to file written criticisms of the draft water permit during the public comment period.

For Maccabee, the situation was unprecedented. “That it would happen on this case that is of such huge public interest and such huge significance from a policy perspective, it’s really troubling,” she said.

Along with WaterLegacy and the tribal communities, the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy has spent more than a decade trying to keep the mine from opening. Aaron Klemz, director of public engagement, said that one of the challenges is that despite the amount of litigation over permitting, there has never been an actual trial where the facts about the mine have been contested. His hope is that those facts will finally come under review if the Minnesota Supreme Court rules the permits sent back by the Court of Appeals have to go through a contested case hearing.

“There are basically two scenarios in which [this mine] goes wrong,” Klemz said. “One is a very long and slow-motion process of water pollution, and the other one is a very rapid and catastrophic collapse.”

The water pollution problems might look similar to what has already happened with iron and taconite mines: sulfates and heavy metals leeching into groundwater and flowing from rivers into Lake Superior. This would also have further deleterious impacts on wild rice beds and fish around the St. Louis River watershed.

As for major collapses, Klemz points to what has happened when tailings basins of the type PolyMet has proposed break open and release pollution downstream. Dam collapses like this have happened in Brazil in 2019, killing nearly 250 people, and in British Columbia in 2014 at the Mount Polley copper and gold mine.

The necessity of copper

Frank Ongaro, the executive director of industry group Mining Minnesota, grew up in the town of Hibbing, where mining was a way of life. After working as president of the Iron Mining Association, Ongaro came to his current position, where he has advocated for the creation of copper-nickel mines around the state. In his opinion, it is completely possible to have these types of mines and protect the environment.

“Every mineral development, every large industrial development—just look at Enbridge’s line 3 replacements, pipelines and other things—they are going to undergo lengthy, thorough environmental review and scrutiny by the agencies,” Ongaro said. “There will always be efforts to push back on those developments, some good, some unreasonable. From a copper-nickel standpoint, we have the metals and the demand is there. The technology exists to be able to mine, extract and process these metals in an environmentally responsible manner.”

In addition to PolyMet bringing jobs and greater economic security to the region, Ongaro also cites the need for copper in a slew of modern technologies, as well as in the development of clean energy infrastructure. Wind turbines, solar panels and electrical vehicles all require copper, and as more of those technologies are built, more copper will need to be mined.

Kelsey Johnson, current president of the Iron Mining Association of Minnesota, agrees that copper is essential if we want to move away from coal and gas. Although she has less experience with copper mines, she feels confident that Minnesota’s history of iron and taconite mining makes the state an ideal place to develop new mines. Minnesota requires lengthy environmental reviews for new projects, she says, which sets it above other countries that might be laxer on environmental protections.

“Where better to build than in a place that has this depth of knowledge?” Johnson said.

Bruce Richardson, the vice president for corporate communications at PolyMet, said by email that he can’t discuss very much due to the ongoing lawsuits over the permits.

“I can say that we have successfully defended six of the 11 state and federal cases challenging the project,” Richardson said. “We are obviously vigorously defending these cases and don’t expect to begin receiving decisions on any of them until later this year.”

July 22, 2016, satellite image of Mesabi Range, Minnesota, USA. (U.S. Geological Survey)

The future of PolyMet

Throwing yet another wrench into the PolyMet saga are a number of changes to federal law that President Donald Trump has initiated which will limit or remove environmental protections. In April, the Trump administration provided a new definition for marshes, wetlands and streams that qualify under the Clean Water Act, as reported by Jeremy Jacobs and Pamela King for Energy and Environment News. The new definition removes protections for most of the country’s wetlands, and environmental groups immediately sounded the alarm over the dangers to many watersheds.

Then in early June, Trump signed an executive order that instructs agencies to waive environmental laws in order for new industrial projects—like pipelines and mines—to move forward more rapidly, in the aftermath of the economic depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even before the federal legislation went into effect, state agencies in Minnesota had already eased regulations of environmental safeguards. According to Jennifer Bjorhus of the Star Tribune, by mid-May the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency had granted almost 430 emergency requests to delay or ease compliance—though the agency also denied a request from PolyMet to defer monitoring nearby wetlands as well as surface and groundwater.

“I think the current federal administration has endangered the health of the vulnerable, environmental protection, environmental justice, racial justice, social justice,” Maccabee said before this new executive order was signed. “If you were going to say, ‘How could we have an administration that would be more destructive of America?’ I think it would be hard to figure out a way to do that.”

As for Klemz, he has his own question about what will happen to the environment if this mining project moves forward.

“Who’s going to be there to tend PolyMet’s grave?” Klemz said. The Department of Natural Resources estimated that restoring the mine area wouldn’t be completed until 2072, but another estimate showed water treatment could be necessary for up to 500 years at the plant site.

“It’ll be there for a long time, and it will continue to be dangerous,” Klemz said. “So who’s going to attend it? It’ll probably be the public.”

This report was made possible in part by the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists. SEJ credits The Hewlett Foundation, The Wilderness Society, The Pew Charitable Trust, and individual donors for supporting this project.

Read more mining coverage from Great Lakes Now:

What are Joe Biden’s views on two of the most controversial environmental projects in Minnesota?

Dependable or Disaster: Safety of Canadian company’s plans for mining in the U.P. under debate

Catch up on more PolyMet news here or Twin Metals news here.

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.Featured image: This Feb. 10, 2016, file photo shows a former iron ore processing plant near Hoyt Lakes, Minn., that would become part of a proposed PolyMet copper-nickel mine. (AP Photo/Jim Mone, File)

1 Comment

-

Can Maccabee be any more dramatic?!?… my Lord…