Great Lakes Moment is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television.

A new study on cleaning up Great Lakes pollution hotspots published in the Journal of Great Lakes Research finds that investing in pollution prevention and restoration pays off in the long run.

Since 1985, U.S. $22.78 billion has been spent on cleaning up Great Lakes pollution hotspots called Areas of Concern, according to the study. It finds that the money has been well spent, with every dollar toward cleanup catalyzing more than $3 worth of community revitalization. In addition, the article concludes that investing in pollution prevention will avoid substantial future cleanups in the long run.

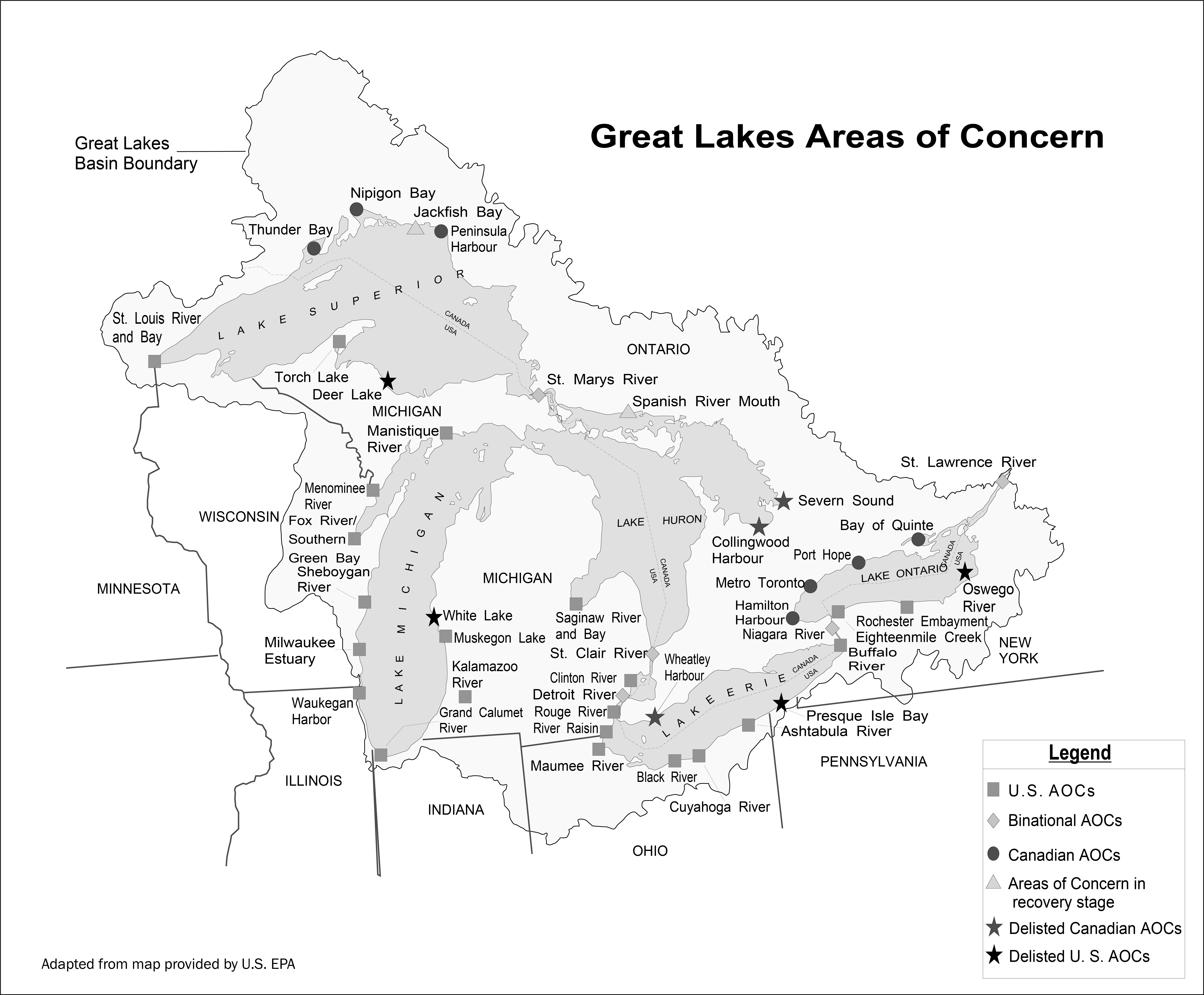

It was back in 1985 that the International Joint Commission’s Great Lakes Water Quality Board reported that progress had stalled in the cleanup of 42 Great Lakes Areas of Concern and recommended developing and implementing remedial action plans to clean up the pollution and restore beneficial uses using an ecosystem approach. Remedial action plans were then incorporated into the 1987 Protocol to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between the U.S. and Canada, giving international legitimacy to the program and providing laser-like focus for all stakeholders to work together to restore uses.

At that time, this was earth shaking for governments because they were used to implementing water quality programs in a top-down, command-and-control fashion. Up until that point, much of their effort was placed on much-needed regulation of industries and municipal wastewater treatment plants. An ecosystem approach called for a bottom-up, collaborative effort.

A 43rd Area of Concern was designated in 1991 – Presque Isle Bay, Erie, Pennsylvania.

Great Lakes Areas of Concern map (Public domain image provided via John Hartig)

An ecosystem approach calls for accounting for the interrelationships among air, water, land and all living things, including humans, and for involving all stakeholders or user groups in problem solving and management. It brings all stakeholders who impact a natural resource or who are impacted by the natural resource together to sit around a table and reach agreement on what needs to be done to clean up and protect their ecosystem.

Can you imagine how difficult that is? Coordinating among disparate groups and reaching agreement on cleanup can be as difficult as herding cats.

This literally was a watershed moment and a paradigm shift in thinking. The first thing to understand is the fundamental distinction between environment and ecosystem. The difference between environment and ecosystem is like the difference between house and home. We see a house or the environment as something that is external and detached from us. It sits over there or out there. In contrast, we see ourselves in a home or an ecosystem, even when not there. A home is where we raise our children, have family meals, celebrate special occasions and entertain friends. What we do to our home and ecosystem, we do to ourselves.

Think of an ecosystem approach as a more holistic way of undertaking integrated planning, research and management of specific places in the Great Lakes. Some have referred to it as grassroots ecological democracy for the Great Lakes.

The incorporation of remedial action plans in the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1987 gave legitimacy to these cleanup efforts and provided a rallying point for people and organizations to come together to clean up and care for their home.

Cleanup of these pollution hotspots has not been easy and required networks focused on gathering stakeholders, reaching agreement on problems and solutions, coordinating efforts, and ensuring that cleanup achieves the desired ecosystem state. In most Areas of Concern, it took over 100 years to reach the state of pollution found in 1985 and solving these problems could not occur in one or two decades. Therefore, sustaining momentum was important. Even with the compelling case of the Great Lakes being a continentally and globally significant natural resource, this was incredibly challenging. For key agency staff and stakeholders, the process has required considerable patience and perseverance.

In general, assessment of problems and causes, and planning, dominated the first 10 to 15 years.

Looking back, continuous investigating, organizing and planning by scientists, managers, and activists created a unified message that eventually led to the authorization of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative in the United States – a federal funding initiative that has provided over $3 billion to the region since 2010.

Being on a pollution hotspot list maintained by the International Joint Commission under the auspices of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement raised the priority for cleanup and helped keep these pollution hotspots in the spotlight over the past 35 years.

Finally, to involve stakeholders in the cleanup process and employ locally designed ecosystem approaches, public advisory committees, stakeholder groups and basin committees were established. In many cases nonprofit organizations like Friends of the Rouge and Friends of the Detroit River were also established to help ensure local ownership of the plans and help champion cleanup and restoration. The important work of these remedial action plan groups and nonprofit organizations cannot be underestimated. They were critical to sustaining momentum, educating citizenry, raising the profile of necessary cleanup, coordinating efforts, advocating for money, and providing continuous and vigorous oversight.

Major dedicated funding for implementation of remedial and restorative actions was not provided in the United States until the enactment of the Great Lakes Legacy Act in 2002 and the establishment of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative in 2010. Indeed, restoration has accelerated in the United States under the Great Lakes Legacy Act and Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. In Canada, early funding was provided through the Great Lakes Cleanup Fund in the late 1980s, replaced by the Great Lakes Sustainability Fund in 2000 and then by the Great Lakes Protection Initiative in 2017. An important funding initiative in Canada was, and still is, the Canada-Ontario Agreement Respecting the Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, first signed in 1971 and updated every 5 to 7 years, most recently signed in 2020.

The Journal of Great Lakes Research study found that cleanup of pollution hotspots leads to reconnecting people to these waterways through greenway and kayak trails, which leads to community revitalization.

Today the Detroit RiverWalk is one of the largest, by scale, urban waterfront redevelopment projects in the United States. (Photo by Detroit Riverfront Conservancy via John Hartig)

For example, cleanup of the Detroit River has led to building the Detroit RiverWalk – one of the largest, by scale, waterfront redevelopment projects in the United States. The cost of construction of the Detroit RiverWalk in the first ten years was $80 million. Economic benefits resulting from building the Detroit RiverWalk in the first 10 years were over $1 billion.

Mark Wallace, president and chief executive officer of the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, notes:

Without this early focus on cleaning up the river and improving water quality, this transformation of the river’s edge would not have been possible.

Paul Sibley, president of the International Association for Great Lakes Research, notes that:

This study shows clearly how a strong foundation of federal environmental laws, working in combination with locally led cleanup processes, can achieve restoration of the most polluted areas of the Great Lakes and catalyze waterfront community revitalization.

Key lessons learned from this study of 35 years of cleaning up Areas of Concern include:

- ensure meaningful public participation;

- engage local leaders;

- establish a compelling vision;

- establish measurable targets;

- practice adaptive management;

- build partnerships;

- pursue collaborative financing;

- build a record of success;

- quantify benefits; and

- focus on life after cleanup and removal from the international Areas of Concern list.

Sibley concludes that:

Lessons learned from this research will be helpful to all groups working to clean up polluted waterways and revitalize communities.

Continued investments through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and the Great Lakes Legacy Act in the United States and the Canada Ontario Agreement Respecting the Great Lakes Ecosystem and Human Health and Great Lakes Protection Initiative in Canada are critical for securing the future of the many communities along this freshwater coast.

Keep up with more Great Lakes Moments at Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes Moment: River otters return to western Lake Erie

Great Lakes Moment: Earth Day turns 50

Great Lakes Moment: Decline of bird species should serve as a warning

Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig is a board member at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. He serves as the Great Lakes Science-Policy Advisor for the International Association for Great Lakes Research and has written numerous books and publications on the environment and the Great Lakes. Hartig also helped create the Detroit River International Refuge, where he worked as the refuge manager until his retirement.

Disclosure statement: The study mentioned in the article was authored in part by John Hartig, and the research was supported by a grant from the Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation, which also provides funding to Great Lakes Now.

Featured Image: Contaminated sediment remediation is underway at the Old Channel of the Rouge River off Zug Island. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Detroit District)

1 Comment

-

Fascinating article. My question regarding this great goal is how such a interconnect network of promising groups, committees and NGOs can help regulate the wastewater treatment facilities on industries who discharge used water back into the lake? And how much power do they have to force harmful activities being shut down?