In late November 2019, an industrial storage site on the banks of the Detroit River collapsed, dumping potentially toxic material into the river.

The Revere Dock event went unnoticed for a week before it sent the city of Detroit and Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy scrambling to determine the cause and assess the damage to the river and threats to the drinking water supply.

A subsequent inspection of riverfront storage sites by the city resulted in discovery of multiple violations and fines totaling $195,000 were levied. But a question remains as to who is responsible for monitoring and enforcing laws and regulations of bulk storage sites that border the region’s waterways.

In Detroit, no governmental entity had been responsible for ongoing maintenance and inspection of seawalls and other waterfront structures until the Revere Dock incident, Crain’s Detroit Business reported. It’s a job that Detroit’s Buildings, Safety Engineering and Environmental Department will now handle.

Responding to a Great Lakes Now inquiry, EGLE spokesperson Nick Assendelft said “EGLE does not regulate the storage of non-hazardous aggregate material and we don’t license riverfront businesses.”

EGLE does enforce what are known as “due care” responsibilities, according to Assendelft. Due care essentially means that a property owner is required to make sure contamination on a property doesn’t cause unacceptable risks.

Who’s in charge?

Storage of industrial material on the banks of waterways is not just a Detroit issue, it’s prevalent throughout the Great Lakes region. Great Lakes Now attempted to get a response to the question of who is in charge by posing it to officials in Milwaukee, Cleveland and Chicago.

All three cities have legacy industries and are in the process of trying to revive their rivers to shake the stigma of the polluting past and make them more accessible and welcoming to the public.

The 1969 Cuyahoga River Fire, Photo by USEPA

In Cleveland, it’s the legendary Cuyahoga River. Milwaukee has a trio – the Kinnickinnic, Menomonee and Milwaukee rivers. In Chicago there’s the namesake Chicago River and the Calumet River to the south. All the rivers mentioned connect to one of the Great Lakes.

In Cleveland, a public works department representative initially suggested calling the U.S. Coast Guard for information on storage then said it’s best to go directly to the mayor’s office.

After two emails and a phone call explaining the issue, spokesperson Andrianna Peterson told Great Lakes Now that a response would be forthcoming.

In the response, mayoral spokesperson Latoya Hunter Hayes referred Great Lakes Now to multiple agencies for more information. There was no acknowledgement that the city had responsibility and a follow-up inquiry went unanswered.

Among the agencies were the Army Corps of Engineers and the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District. Army Corps Buffalo district spokesperson Susan Blair said that storage sites on the banks of waterways are not the responsibility of the Army Corps. The sewer district did not respond.

Milwaukee and Chicago

Milwaukee’s response was similar to Cleveland’s.

A phone message and two emails sent to the city’s Department of Public Works went unanswered. A follow-up response from a city call center representative referred Great Lakes Now to the Wisconsin DNR as the proper agency.

Wisconsin DNR spokesperson Sarah Hoye said several bulk storage sites in Milwaukee’s harbor that hold material like salt, oil tanks and recycling cement are covered under a general permit.

The “general permit does not have an explicit requirement to check or monitor structural integrity of breakwalls and bulkheads,” Hoye said. The city may conduct inspections for structural integrity and there have been “no historic issues with structural failures causing discharge at these facilities,” according to Hoye.

Milwaukee’s port is a department of the city of Milwaukee.

Great Lakes Now was not able to contact the city of Chicago. Its Department of Environment under Mayor Lori Lightfoot has not yet been fully restored despite campaign promises to do so. Former Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel disbanded the department in 2012.

Great Lakes Now contacted the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency with questions about responsibility for regulation and monitoring of storage sites on Chicago’s waterways.

Generally, “a facility that handles or stores raw materials, products, waste materials, or by-products and such materials that are exposed to stormwater must comply with the terms and conditions of Illinois’ (National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permit for stormwater discharges from industrial activities,” said spokesperson Rebecca Clark.

Clark declined to answer specific questions about any incidents of spills from storage sites to waterways, results of inspection reports and the need to increase monitoring of sites in light of increased risks based on high water levels and more intense storms.

Information on those specific questions would require a Freedom of Information Act request, according to Clark.

Under the radar

A Chicago environmental organization shed light on the confusion.

Meleah Geertsma, Senior Attorney Natural Resources Defense Council, Photo by NRDC via Gary Wilson

Bulk handlers and storage sites of industrial material and waste tend to “fly under the regulatory radar,” said Meleah Geertsma, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s environmental justice team in Chicago.

Storage sites don’t get the same attention as a refinery or steel mill would, and regulation and oversight can be split between agencies, allowing issues to fall between the cracks, according to Geertsma.

Storage site operations tend to run with a basic, decades-old approach, she said, meaning they are not employing available modern controls.

“Even their adherence to old control methods is spotty,” she said.

Milwaukee Riverkeeper Cheryl Nenn expressed similar concerns about industrial waste storage on the banks of Milwaukee’s rivers.

Cheryl Nenn, Photo by Milwaukee Riverkeeper via Gary Wilson

“Most industrial general permit holders are not monitored or surveyed frequently,” Nenn said, and she’s not aware of enforcement incidents.

As a riverkeeper, Nenn said when she has questions about a storage site and asks the state agency for information, they don’t have it and must go to the storage facility for it. Many facilities are required to self-monitor but “don’t actively supply that information to the state agency,” according to Nenn.

Nenn said at the federal level environmental groups are lobbying the U.S. EPA to focus on banning or restricting storage of industrial waste in floodplain zones and along waterways.

Nenn cited the Port of Milwaukee as a site that has active piles of material in storage, some of which may be toxic.

Milwaukee’s waterways can be “very vulnerable to pollution from those piles,” Nenn said and noted that the port was under several feet of water after a January storm.

Hierarchy of restoration

NRDC’s Geertsma sees another issue in play when it comes to the Great Lakes region’s legacy waterways. She refers to it as a “worsening hierarchy of restoration.”

“Midwest cities such as Chicago are increasingly looking at their waterways as potential amenities instead of the sewage and industrial conduits of the past, “she said.

She cites gentrifying areas that are restored to include waterside condominiums, boating opportunities and breweries.

“But this view doesn’t apply equally across the city,” she said.

That means the industrial activity that remains tends to be clustered in low-income black and brown communities that “bear the heaviest legacy of contamination,” Geertsma said.

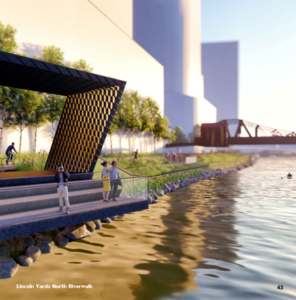

An example in Chicago is the city’s massive Lincoln Yards redevelopment of an industrial corridor along the north branch of the Chicago River. It will include the natural and cultural amenities that Geertsma referenced in her “worsening hierarchy of restoration” scenario.

Metal recycler and scrapyard operator General Iron, whose site is adjacent to the project, will leave the area and relocate to Chicago’s heavily industrial Southeast side, where residents have long-struggled with pollution issues.

There needs to be real action to acknowledge the trend or the result will be “an increasing gap between those who experience the waterways as healthy, vibrant places and those who are poisoned by them,” Geertsma said.

Friends of the Chicago River Executive Director Margaret Frisbie told Great Lakes Now that “efforts to develop the river must embrace all the people and more must be done to create equity” between industrialized and developing neighborhoods. Industries operating in neighborhoods should be subjected to the highest level of standards and permits, according to Frisbie.

U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib’s district is highly industrialized and downriver from the site of the Revere Dock toxic spill into the Detroit River. It is also home to one of the most polluted zip codes in Michigan.

“This incident appears to be yet another example of the need to have tight safeguards for industry, especially those who operate near resources that millions depend on,” Tlaib said in a statement after the spill.

Featured Image: Contaminated sediment remediation is underway at the Old Channel of the Rouge River off Zug Island, Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Detroit District

1 Comment

-

If you think this is difficult, wait until the old industrial barge conduit on the Chicago River finally breaks down and fails to stop even a few Asian Carp from getting into the Great Lakes. This ugly species is pretty much industructable and will completely wipe out virtually all the edible fish in all the Great Lakes. Asian Carp are already killing everything around river fisheries South of this point. No fishing folks! Even the Canadians will get nailed on this one–we are talking about virtually ALL the fish including smaller feed stocks that support

most of the sea life. The beautiful blue Great Lakes will be sewer water. Get used to it or take responsibility and fix it!

–Ed Ely