Tiny bits of plastic have been making big news lately for turning up just about everywhere – in our drinking water, food and even in the air we breathe. They are called microplastics, and researchers are only beginning to glimpse their health effects.

Much of the contamination can be chalked up to the fact that we recycle only 9 percent of plastic wastes. The rest — water bottles, pens, shopping bags — can end up in our lakes and rivers, where they are exposed to sunlight and waves that break them down into smaller and smaller bits.

Now a new study in Muskegon Lake, linked to Lake Michigan just north of Grand Rapids, has found that a group of chemicals known as PFAS can stick to microplastic particles in the water. Since fish routinely ingest microplastics, this increases the likelihood that PFAS will make its way into the bodies of fish-eating creatures – including us.

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are human-made chemicals used in many common products such as non-stick cookware, takeout food boxes and stain-repellent fabric. PFAS don’t degrade easily and are resistant to water and oil.

But these qualities, which make them ideal for various consumer products, raise health concerns. They can persist for years in lakes, rivers, wildlife and people and are known to increase the risk of cancer, decrease fertility, disrupt thyroid hormones, and impact growth and learning in infants and children.

Some water treatment plants can remove some but not all PFAS. As Great Lakes Now reports, the chemicals have been detected in an increasing number of people’s water systems in Michigan and other states and provinces.

Getting out of the lab

Lab-based studies show that when both contaminants are in water, PFAS will stick to the surface of microplastics. John Scott, an analytical chemist at the University of Illinois, wondered if the same thing happens in a real lake.

“I haven’t seen anybody else look at this in the natural environment,” he said.

Scott’s study showed that not only does it happen, the effect is magnified. More PFAS sticks to microplastics in lake water than in the lab, where researchers use simulated lake water. This simulated water is deionized water to which researchers have added the calcium, sodium and chloride that would normally be found in lake water. But unlike real lake water, it does not include organic matter and polluting compounds.

Rachel Orzechowski, a research assistant at AWRI, Grand Valley State University, sets up microplastics samples to submerge for 1-3 months in Muskegon Lake, Photo courtesy of John Scott

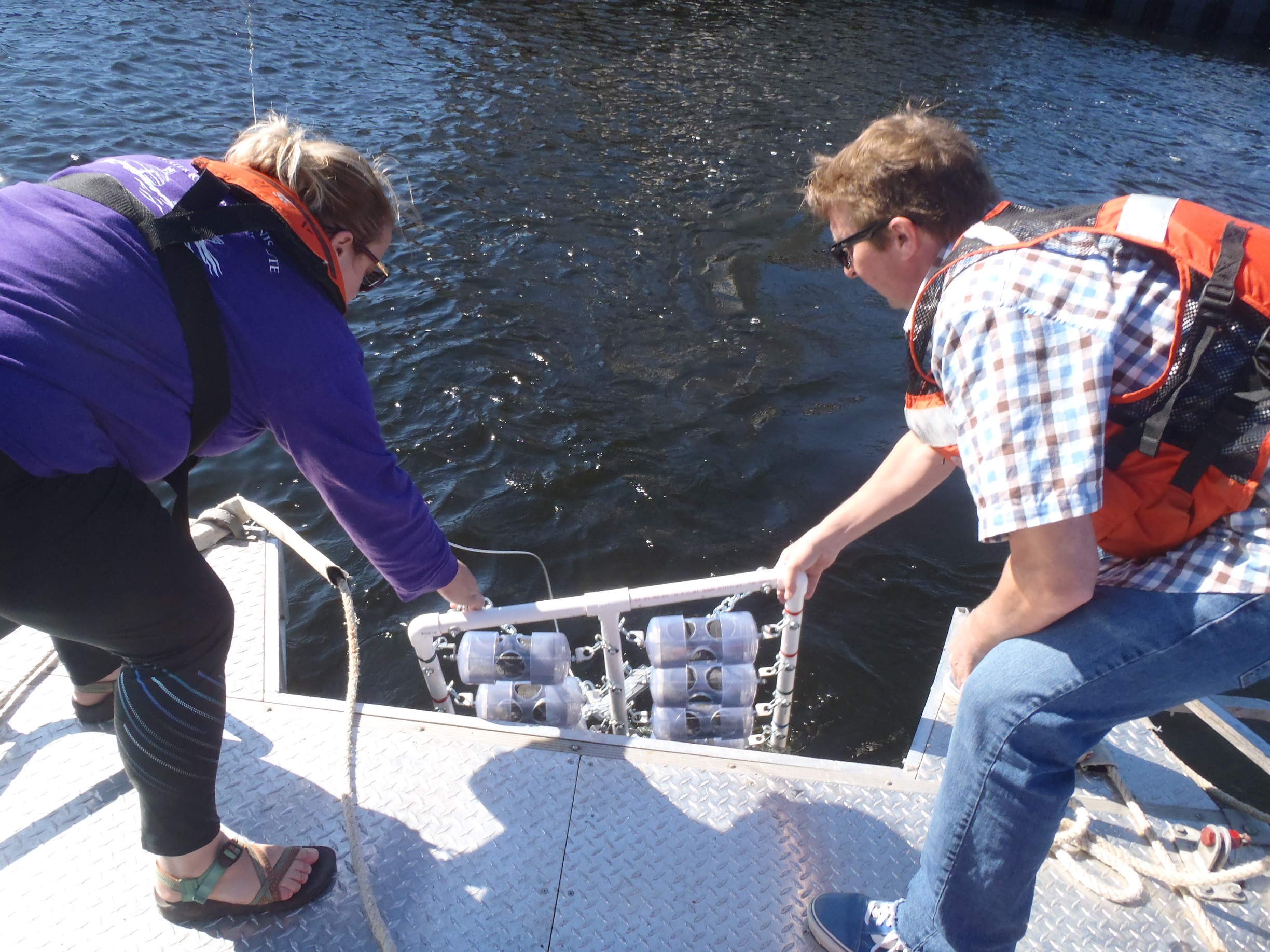

Oudsema, a research assistant at the Robert B. Annis Water Resources Institute (AWRI), Grand Valley State University and John Scott, Illinois Sustainable Technology Center, lower microplastic samples into Muskegon Lake, Photo courtesy of John Scott

Scott and his team submerged microplastic samples in the nearshore waters of the channel connecting Muskegon Lake and Lake Michigan. They also placed samples in the middle of Muskegon Lake. After one month, and again after three months, they tested the microplastic for PFAS.

The researchers found that regardless of location, length of time or type of plastic tested, PFAS in Muskegon Lake adhered to microplastic particles, ranging from .052 nanograms to .87 nanograms of PFAS for each gram of plastic.

When they did the same experiment in the lab, they found the amount of PFAS sticking to the microplastic was notably less.

The difference may be because microplastics in lake water are often coated in organic matter, metals or biofilm, which makes the surface easier to stick to, said Scott. Biofilm is a collection of bacteria that grows on microplastic particles in the lake.

How concerned should we be?

“The concentration in the lake samples are not very high,” said Scott. “A fish would have to eat a lot of microplastic to get any level of concern.”

But as he points out, it’s very likely that PFAS aren’t the only compounds sticking to microplastics.

“If you look at all the chemicals, heavy metals and pathogens in the water, this could enhance adverse affects,” he said.

Also, Scott’s microplastics were submerged in lake water for just three months. Microplastics have been detected in the Great Lakes for decades.

Loyola University Chicago aquatic ecologist Tim Hoellein – who was not involved in the project – says Scott’s study is a first step toward understanding possible health effects. We still know so little about how microplastics and the substances that cling to them move through aquatic systems.

That’s because microplastics are unique, said Hoellein. While lake water is full of naturally occurring microparticles such as clay or sand, none are quite like microplastics – slow to degrade and buoyant.

“I know it can be alarming when people think about their drinking water or the fish they’re eating,” he said. “But we’re on the way to coming up with solutions. This information is part of doing our best to make improvements.”

Featured Image: Microplastics, Photo by noaa.gov

1 Comment

-

I believe we can help by saying No to non-stick cookware and other PFAS-coated items and also by avoiding polar fleece fabrics (I know, I love my warm fleeces, too). When you wash those fabrics, microplastics are released into the water system, and water treatment plants are not equipped to remove them. I suppose it also makes great sense to continue to collect trash on the beaches, especially plastic and styrofoam of the “tiny” variety (there’s plenty of small visible plastic to collect.). There are a number of people who don’t mind this futsy work, bc of the view : )