Editor’s Note: This post is part of a series taking a look back at 2019

Hundreds of miles of undeveloped Lake Superior coastline were finally interrupted to reveal our destination: Duluth’s downtown and the iconic Lift Bridge that freighters and other vessels pass under to dock in the westernmost harbor of the Great Lakes system.

Eighteen of us had been aboard the 70-foot sailboat “Arctos” for some 48 hours sailing across the lake in search of competitive success — and cold beer, if I’m being honest. We saw the skyline pop through an overcast August sky.

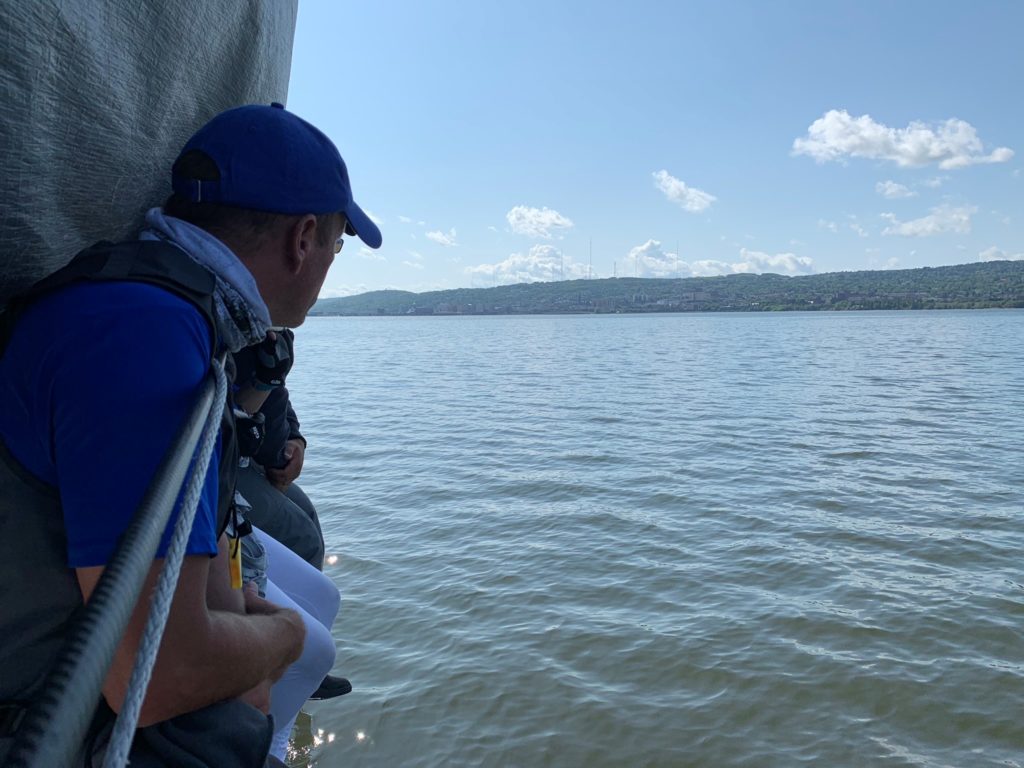

Mike Hoey sits on the rail of Arctos nearing the finish of the 2019 Trans Superior Race. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

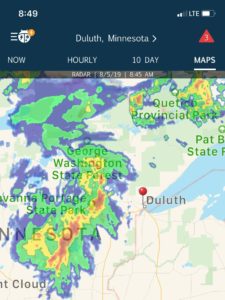

And now, being that close to civilization meant cell signals got through, which meant weather information was readily available as we sat on deck and looked at our phones.

A nasty storm front was coming. People at home in Detroit were texting me about it.

The line of red, orange and yellow on our weather apps meant unpredictable winds that could blow us off course. Predicted gusts of up to 60 mph meant safety concerns, so we donned rain gear and tethered ourselves to the boat.

We thought less about how the boats “Talisman” and “Stripes” – our fierce competitors but also good friends from Detroit – were in striking distance of taking away our lead and more about how we would keep each other and the boat safe in what could be some dangerous conditions.

We waited for the storm front and watched Duluth disappear in its clouds and rains as it headed towards us.

THREE SUMMER RACES, THREE LAKE CROSSINGS

The Trans Superior race is held every two years, and this year’s completed a trifecta of Great Lakes long-distance sailboat races for Arctos and me. Many on the crew also competed on different boats in the three races that traverse lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior.

First there was the 333-mile Chicago Mackinac Race, which started off in the Windy City on July 13 and saw a fleet of some 265 boats reaching the iconic Mackinac Island around two days later.

Arctos docked at Chicago Yacht Club before the start of the 2019 Chicago to Mackinac Race. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

That was a relatively painful race for the 17 men and me aboard Arctos, including owner Chuck Bayer, Jr. Light winds and inaccurate weather predictions made navigating for advantage a challenge. A few crew personalities didn’t always mix well. But it’s hard to complain about any time on the Great Lakes, especially with a group of accomplished sailors who forgive each other’s differences of opinion, personality and ability.

I wouldn’t compare sailing a yacht up Lake Michigan to true noble pursuits that better society, but yacht racing is an opportunity for a team to work together, rely on each other’s strengths, and overcome weaknesses to keep everyone safe and reach the finish line.

This year it was fresh in our minds how that doesn’t always happen. Just a year ago we were one of the boats that dropped out of the Chicago Mackinac race soon after starting to help search for a crew member on another boat who had fallen overboard in relatively rough conditions. After several hours of unsuccessful searching, Arctos returned to the docks for a grim dinner.

A few days later the sailor’s body was found, and the boating community became a little less about competition and more about reflection. A U.S. Coast Guard inquiry revealed his life vest failed to inflate, and sailors around the Great Lakes doubled down on safety going into this summer’s distance races.

Owners that I race with, like Bayer and Cynthia Best, required crews to take the U.S. Sailing Safety and Sea course before this year’s distance races, and all of us seemed to check on each other just a little more closely.

“There’s a lot more concern about the inflatable life jackets, their maintenance, re-arming them (with air cartridges) to give them a probability of actually working,” said another Arctos crew member, Todd Jones, who owns Thomas Hardware, a marine supply store in Grosse Pointe Park, Michigan.

His customers didn’t usually explicitly mention last year’s tragedy in the Chicago race, “But you know that was the source of it,” Jones said. “Even my wife and kids were like ‘Is all your gear going to work?’ and people have never brought that up before in my 37 years of Mackinac racing.”

The Chicago Mackinac Race this year was calm. Arctos didn’t have a stellar finish, but the three days on the water was a good warm up for me for the Lake Huron contest, which started July 20.

RACE NUMBER TWO

The Port Huron-to-Mackinac Race, unlike the Chicago one, has two courses. The shorter route takes more cruising-style sailboats along the mitten’s eastern shoreline to Mackinac Island, while the longer route has boats sailing a northeasterly route toward Georgian Bay before turning left and charging across the top of Lake Huron toward the finish.

Check out Detroit Public TV’s documentary “Mackinac: Our Famous Island” here.

Arctos had a great race, winning her class and giving Bayer another sailing accomplishment to brag about: it was his 50th time competing in the race. But I wasn’t with them. Instead, I joined the all-female crew of Phantom, a J-105 owned by Cynthia and Jim Best of Brighton, Michigan.

Owner Cynthia Best aboard Phantom approaching Mackinac Island in the 2019 Bell’s Beer Bayview Mackinac Race. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

Seven of us were on board, with a collective 60-plus Mackinac races between six of us. It was the first race for Justine Buda, a 25-year-old nursing student who learned to sail after taking a class in Detroit two years ago. She was the newcomer but fit right in with the rest of us who have known each other, sailed together and been friends off the water for, in some cases, decades.

Phantom was the only boat with an all-female crew in this year’s race, but certainly not the first in the race’s history. In 1983 a team sailed a 33-foot boat in one of the roughest races in recent memory. But being a women-only team meant some media attention for us anyway. One of us appeared on a local TV morning program, I talked to a commercial radio station in Detroit and a national sports talk network, and the Mackinac Island Town Crier published a feature about us, complete with a dockside photo snapped just after we finished.

The crew of Phantom after the finish at Mackinac Island. Front row, left to right: Justine Buda, Cynthia Best, Jennifer Lech, Tricia Smotherman, Sandra Svoboda. Back row, left to right: Lauren Wake, Laurie Bunn. Photo by Brent Ross.

I have mixed feelings about the media attention. We really weren’t that different than any other team – a group of friends sharing a bit of an adventure and a competitive challenge.

But look around any harbor or race course and you will see mostly men on the boats. If our team inspires any women or girls to learn to sail or sail more, then we’ve made some kind of impact.

The race itself didn’t disappoint. Saturday’s gorgeous afternoon turned into a stormy evening. We dropped sails to make the boat easier to control and harness in. After maybe 20 minutes of fierce weather, the front blew through and the sky produced one of the most gorgeous sunsets we’d ever seen.

After a storm, the first sunset during the 2019 Port Huron-to-Mackinac race was vivid. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

We continued up the lake and took a battering crossing the top. The boat slammed into waves, especially in the dark when the helmsperson can’t see to steer, and everything down below was wet and cold. We lived on cookies, pizza, chocolate-covered espresso beans and some kind of breakfast muffins.

“We do this for fun?” we all joked.

But reaching the island on a warm, sunny day with spouses and boyfriends there to meet us was worth it – it always is.

Two weeks later, I headed back up north and crossed the Straits by car for the Trans Superior adventure on Arctos.

FREIGHTERS AND FINISHES

We had climbed onto the boat in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, Saturday morning, traversed the Soo Locks, and traveled along with freighter traffic to reach the starting line in Whitefish Bay. Thirty-eight boats started the 375-mile race, which is organized by the Duluth Yacht Club.

Before the start of the 2019 Trans Superior Race, sailboats go through the Soo Locks. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

On Saturday afternoon, we sailed in strong enough winds at first to be on course for a Sunday-night finish. But then we bobbed and drifted on the glassy waters off the Keweenaw Peninsula for most of Sunday with little and sometimes no breeze. Lake Superior was not living up to its reputation as a feisty, cold, rough lake – not that we wished for those conditions.

Late Sunday and into early Monday the breeze filled in, and by mid-morning we were leading the fleet of across Lake Superior in steady breeze that had us on a fast clip toward Duluth.

Arctos was not winning, based on the race’s handicapping system that calculates and adjusts positions based on a variety of factors like the size and design of boats. But we were excited to be out in front and hoping for “line honors:” first to finish status, which would be the first time for many of us on board to earn in a long-distance sailing race.

Closing in on Duluth, with a few of our closest competitors in sight, we weren’t secure in that position.

With the storm approaching, we became more concerned about safety than the race standings. My watch was on deck as it approached and took the time for a briefing. Even though we’d all been through big weather and were familiar with changing sails, Mike Hoey talked us all through all the steps and who would do what when the big winds hit.

Mike Hoey (blue hat) leads a crew discussion aboard Arctos during the 2019 Trans Superior race. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

It all went as planned. The front came. We changed sails. We lost sight of other boats and shore for a bit. Nothing broke. No one got hurt.

And the sun came out for the last couple hours of the race.

As the first boat to finish, we were accompanied in by a photo boat, and spectators along the harbor entrance cheered.

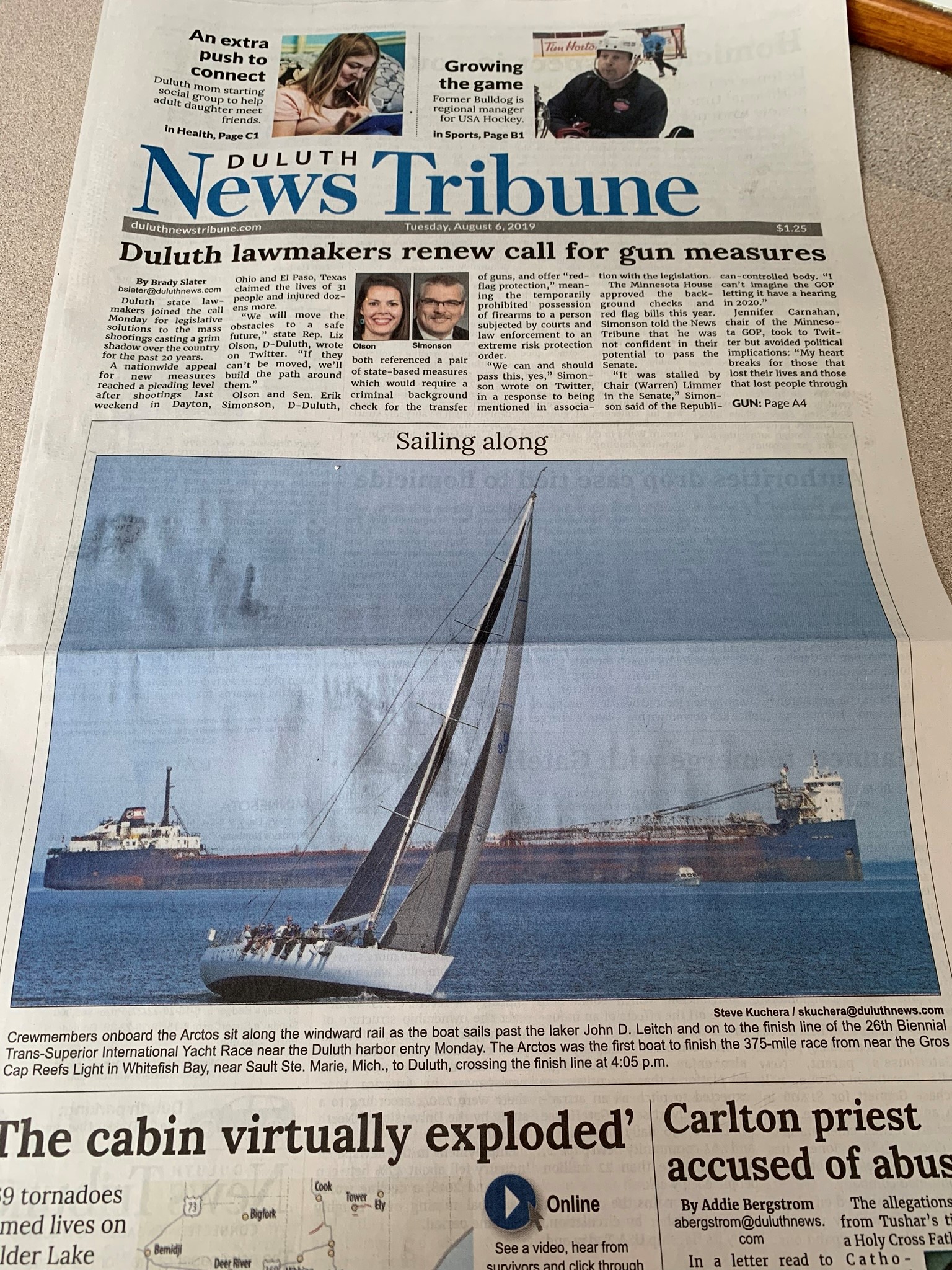

The next day, our photo was on the front page of the Duluth News Tribune.

Arctos made the front page of the Duluth News Tribune after claiming “line honors” in the 2019 Trans Superior Race. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

“That’s one of the reasons I bought this boat: winning line honors,” Bayer will tell you. “That and so I can go sailing with so many of my friends.”

Here’s to next season!

Featured image: Aboard Arctos during the 2019 Trans Superior sailing race. Photo by Sandra Svoboda.