It was probably inevitable that Tracie Baker ended up working at Wayne State University’s Integrative Biosciences Center in what she named the Warrior Aquatic, Translational, and Environmental Research—or WATER—Lab.

She grew up in Ohio, near Lake Erie, went to Cleveland State University on a Division I swimming scholarship, continued on to study marine biology, went to vet school for fish and aquatic animals, and got a PhD in molecular and environmental toxicology.

Tracie Baker, DVM, PHD Principal Investigator and Director, WSU WATER Lab

“I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, I just knew that I wanted to basically work with fish health, so whether that would be working for DNR, EPA, doing fish health, I knew I probably wasn’t going to end up having a clinic where people bring their fish in,” Baker said.

Though Baker does some minor consulting for friends and family who call about their sick fish, what she actually does at the WATER Lab is research contaminants and their impacts on fish and humans.

Baker and her team just wrapped up a massive project, looking specifically at a variety of contaminants in the Detroit River, including PFAS, a family of industrial contaminants with largely unknown impacts on human and environmental health. The last sampling was completed in the fall, and they’re working on writing up the results of that research now.

Beyond that, Baker recently did a TED Talk on her research into contaminants and their consequences. Through her Twitter account, @bakerwaterlab , she also tries to encourage people to reduce the amount of contaminants in their lives with tips under the tag #toxfreethursday.

Great Lakes Now spoke with Tracie Baker. Here’s an edited transcript of that conversation:

Great Lakes Now: What kind of projects does the water lab handle? Is it all roughly similar to what you’re doing with PFAS and the zebrafish?

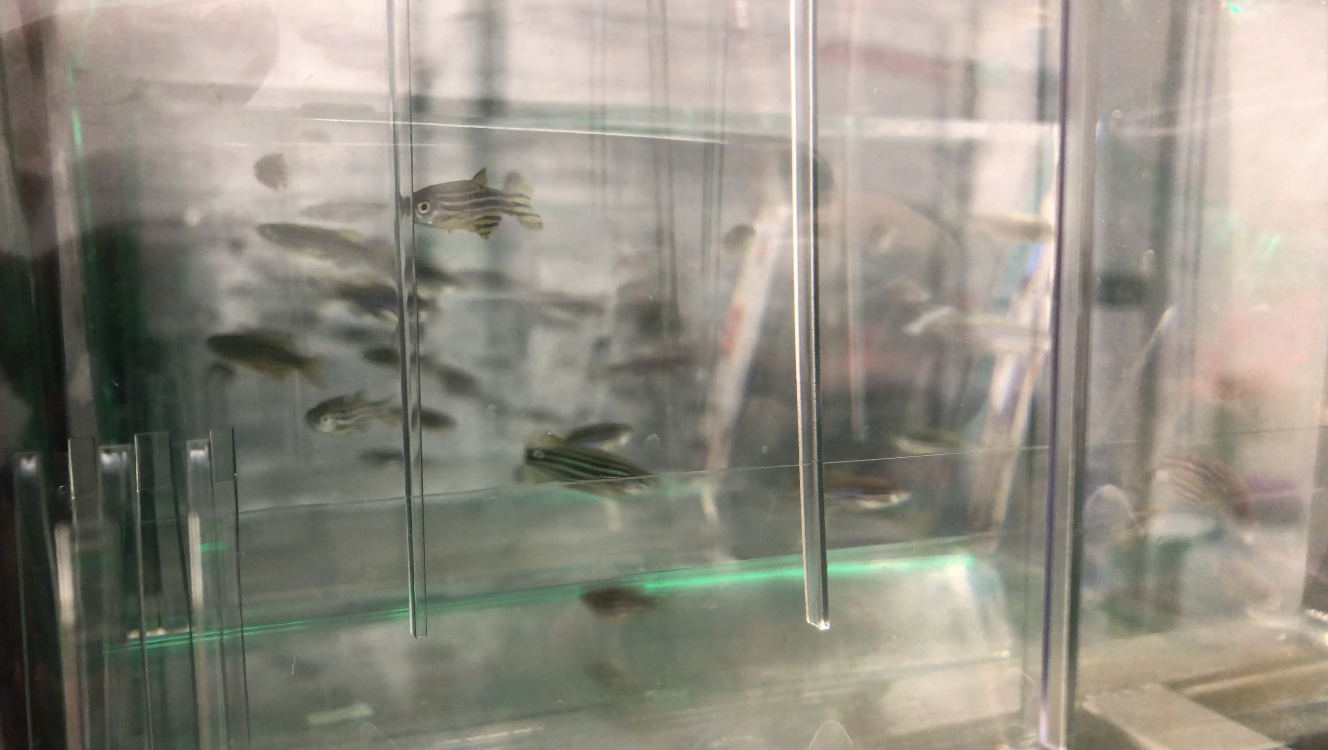

Tracie Baker: We use the zebrafish because they basically have 84 percent of the genes that we know are involved in human health and disease. Also we can use them to study fish but we can also use them to study human health, so it all kind of centers around that. We’re looking at a lot of the emerging contaminants but we’re also looking at other contaminants and how they can cause effects two generations later and then looking really specific at the mechanisms of the genes that are involved.

GLN: What prompted this project in particular?

TB: When I came here not quite four years ago, I was really interested in how they were finding a lot of these emerging contaminants, pharmaceuticals, personal care products in the Great Lakes. But I really wanted to focus on Detroit and the Detroit River specifically.

I wanted to look at it over two years, do a number of samples, and then I wanted to look at all of these different sites and kind of see how it was changing, so I think just my interest in the health of the Detroit River and how that plays into drinking water sources as well as effluent from wastewater treatment plants.

GLN: Is that something you learned in vet school, that zebrafish are a good option?

TB: I actually learned it after vet school. My PhD work was at a zebrafish lab at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Zebrafish are being used more and more as a human health model. It used to be mostly rats and mice and primates. Zebrafish have been used because they regenerate, like they can regenerate their fins, they can regenerate their hearts, so it’s been used in different forms of medicine and it’s just starting to be used in toxicology where its gaining more interest.

GLN: How is it compared to using rats? Is it closer, is it more effective or is it roughly the same, just a different animal?

TB: It’s different because different systems are more conserved. Rats or mice are mammals. They’re similar to us in that way. The fish I really like because it’s translatable to fish in the river and the lakes and then as well translatable to humans.

And zebrafish develop really quickly. In five days all their organ systems are formed and functioning and they’re swimming, so you can look at development. That’s kind of who started using them to begin with. And they’re clear, so you can see through them. So you can watch all their organ systems develop in a quick period of time. And then one female can lay 300 eggs every week, so you can also get these huge numbers so when you’re looking at a bunch of chemicals, you can do high throughput analysis, where basically you can look at very large numbers over a pretty short amount of time.

GLN: Did you find what you expected to find? Was there anything surprising?

TB: I expected that we would find something. I was really surprised by the number of artificial sweeteners. The highest level of any chemical we found was artificial sweeteners and sugars. These are things that are in our food, especially beverages, and can be used as preservatives and because they’re synthetic they don’t break down, so they just stay in the environment for a long time. Most of them pass through us pretty much unchanged and then they go out in the wastewater treatment. So that surprised me, especially how high of levels we found, and then number of antibiotics surprised me and seeing caffeine, that surprised me as well.

I didn’t know what to expect, especially since I just moved here and I wasn’t sure what was in the water and there wasn’t a lot of research that had been done specifically in this area.

GLN: What comes after this project?

TB: I think it will give us this preliminary data that will help us focus our next projects and then we’re also really interested in looking at the fish that are in the water to see are these chemicals in those fish, and if we’re eating the fish are we getting the chemicals back in that way and then looking at what exactly is coming from the wastewater treatment plant and what is going into the drinking water treatment plant and how things are taken out during that process too.