In a move to restore a prehistoric giant that once called the Maumee River home, wildlife officials, with the help of the public, released the second of 20 groups of lake sturgeon at Walbridge Park in Toledo on Oct. 4.

A total of about 3,000 six-inch fish were released a dozen miles upstream from Lake Erie. Another 3,000 will be released annually for the next 18 years. The first 3,000 were released a year ago.

The Maumee River Sturgeon Recovery Group’s project is a collaboration between state, federal and Canadian agencies. Participants include wildlife managers and scientists from the universities of Toledo and Windsor, The Toledo Zoo, Ohio and Michigan departments of natural resources and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment.

A tank filled with soon-to-be-released lake sturgeon, Photo by James Proffitt

Sturgeon eggs were collected from fish in the St. Clair River, which boasts a healthy population. About half the fish were raised at the Genoa National Fish Hatchery in Wisconsin. The other half were raised just a hundred yards from the Maumee River, in a special trailer operated by The Toledo Zoo.

In 2018, more than a thousand people came to the inaugural release, and this year, at least several hundred. The Toledo Zoo sells sponsorships for the fish each year. If a sponsored fish is ever caught, its sponsor will be contacted with information about their fish.

But folks don’t have sponsor a fish to release one – it can be done for free. Chris Vandergoot, director of the Great Lakes Acoustic Telemetry Observation System (GLATOS) headquartered in East Lansing, has been keeping track of last year’s released sturgeon. Vandergoot said involving the public in the releases is great to see because it helps build a sturgeon fan base.

“We hope this is an annual thing. Fish aren’t viewed as being as cuddly as other wildlife, so support by the public for a project like this is very important,” he said. “Events like this can only help moving forward with public interest and outreach and education.”

Released sturgeon being tracked

Vandergoot has been keeping track of last year’s batch of sturgeon with GLATOS.

“Forty of the approximately 3,000 we stocked last year have these acoustic transmitters in them and what we’re doing is using GLATOS to track their movements post-release,” he said. “What was kind of interesting is we downloaded these receivers just recently and better than 80 percent of them migrated out of the river fairly quickly after being stocked, within a week. And within a couple hours we began seeing downstream movement.”

USFWS fish biologist Justin Chiotti displays a pair of PIT tags, Photo by James Proffitt

Some of the fish, Vandergoot said, stayed in the river and were detected well into autumn. A good number have traveled as far as the Lake Erie reefs east of Toledo in Ottawa County.

“As of August or early September they were detected all in the Maumee River and the Western Basin,” Vandergoot said. “The fish we released in 2018 are now between 12 and 15 inches or so, and we’ve gotten reports of some commercial fishermen finding some of those in their trap nets along the western edge of the Western Basin.”

The GLATOS system includes about 1,500 receivers throughout the Great Lakes and picks up signals from fish which have been fitted with electronic transponders.

“We probably have about 200 receivers out in Lake Erie,” Vandergoot said. “Most of them you’d never know they’re there.”

Those fish without acoustic transmitters will also be tracked, when possible, using passive integrated transponders, or PIT, tags.

“Every fish released today contains one of these tags. It’s the same tag that’s in your pet,” explained USFWS fish biologist Justin Chiotti. “If any of these fish are recaptured in the Great Lakes by sturgeon researchers or even researchers who don’t do sturgeon research they have a PIT tag scanner on their boat. So if they ever capture one of the fish that was released today all that information goes to a database.”

Chiotti said information about where a fish was found, its size, weight and other important information will help scientists keep tabs on the released fish and gauge their range, size and health among other things.

Sturgeon fulfill a role in the Lake Erie ecosystem

In Ohio, lake sturgeon are classified as a threatened species, which requires their immediate release. No eating, no taking to the taxidermist for a wall mount. So what’s the point?

“The point is they’re a native species and they fulfill a role in the ecosystem just like every other species,” said Vandergoot. “One of the big benefits of lake sturgeon is they’re a host for a variety of freshwater mussels and we all know mussels filter out water. We’ve seen a large decline in native mussel species in the Great Lakes, and in Lake Erie in particular.”

While some of that decline can be contributed to invasive mussels like zebras and quaggas, he said, restoring sturgeon can only help.

A freshly landed 60-inch lake sturgeon from Minnesota. It was released just after landing, Photo provided James Proffitt

“Mussels actually attract fish over to their shells when they’re reproducing,” Vandergoot said. “Then they’ll release their glochidia (tiny mussel offspring) into the water column and the fish will ingest that water and the glochidia will lodge in their gills, then drop off later in some other area.”

Lake sturgeon in the Great Lakes can reach lengths of 10-plus feet and approach 300 pounds. The largest fish taken from Lake Erie was caught by in 1929 and weighed 216 pounds.

Young sturgeon like the ones just released are protected from predators by sharp, bony plates called scutes. As they grow in size, the scutes remain though become softer. Once sturgeon survive the first year or two, they are fairly safe from natural predators due to their size.

Male sturgeon reach sexual maturity at about 15 years and female at about 20 years. They reproduce only about every five or so years and can live up to 150 years, reproducing their entire adult lives.

Sturgeon weren’t always held in high esteem

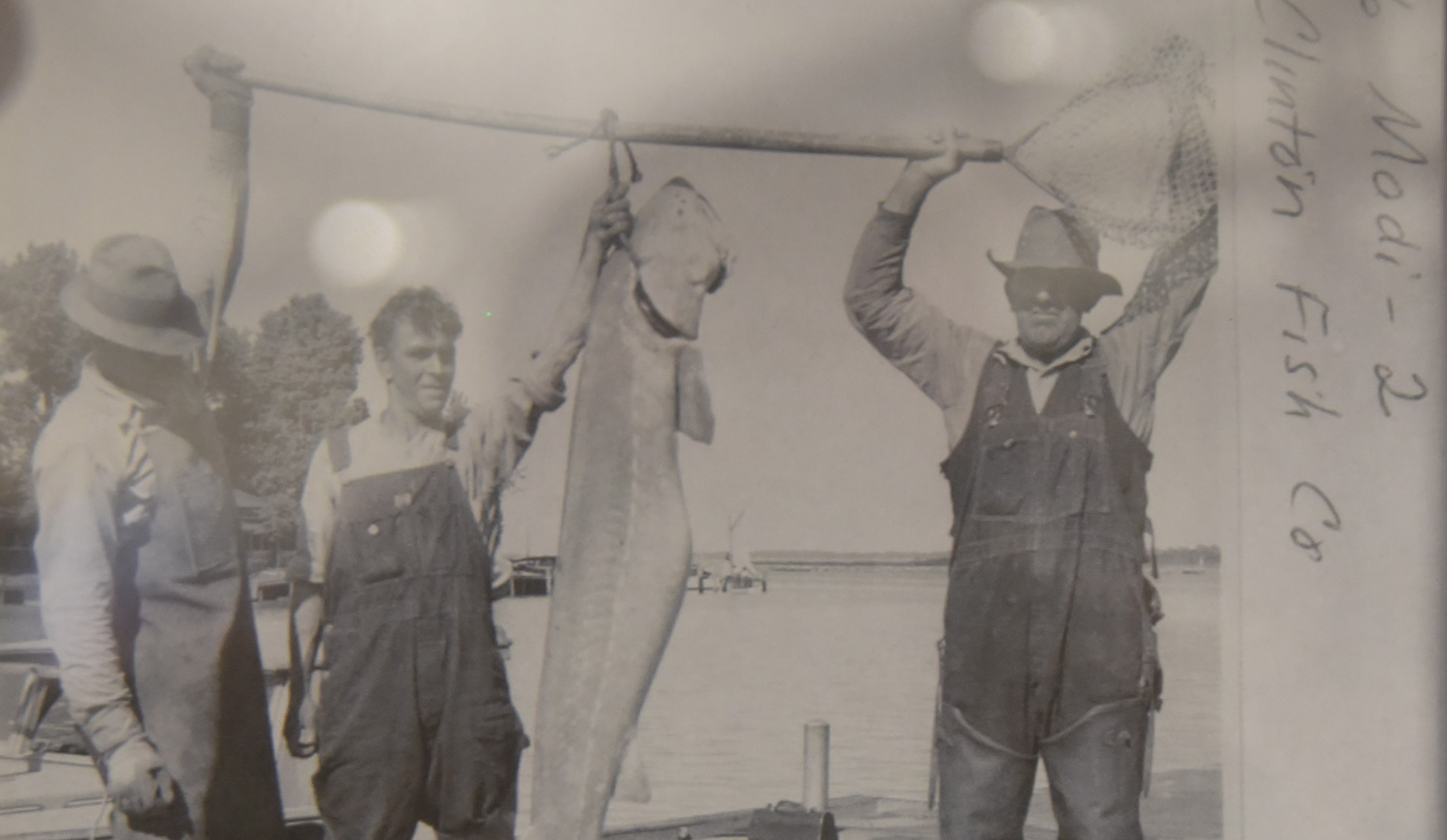

Up until about 1850, commercial fishermen considered sturgeon a nuisance. When caught in nets, the massive fish often destroyed the nets and other fishing gear, which led to their frequent killing. At one point sturgeon were so plentiful they were stacked on the banks and burned by fishermen.

By the late 1800s, commercial fishermen began recognizing the monetary value of the Great Lakes’ biggest fish.

“Initially there were a lot of sturgeon killed because they did so much damage to the nets, but at some point they realized how valuable the eggs were,” said Travis Hartman, who oversees Ohio’s Lake Erie fisheries programs. “Then they started harvesting them to harvest their eggs.”

Those eggs were taken from female sturgeon and shipped to Europe as expensive caviar.

A tiny sturgeon patiently awaits its release into the Maumee River, Photo by James Proffitt

Records indicate that between 1879 and 1900 commercial fishermen pulled an average of 4 million pounds of sturgeon from the Great Lakes each year. The largest year ever was 1885, with 8.6 million pounds harvested, of which 5.2 million pounds came from Lake Erie.

By 1900 their numbers drastically dropped and just two decades into the century, little commercial exploitation of the fish remained due to their scarcity.

Experts agree that overfishing and loss of habitat were the main contributors to sturgeon’s near-disappearance from the Great Lakes. One major reason for habitat loss was the damming of lake tributaries, which prevented sturgeon from reaching many of their historical upstream spawning grounds. Historical records show sturgeon spawning almost to Lima, in the Ottawa River.

The 1913 Ballville Dam on the Sandusky River in Fremont was removed in 2018, and may lend credence to the loss of habitat idea. An angler fishing a few miles upstream of the former dam site hooked a big sturgeon just months after the dam’s removal.

“That’s probably the first sturgeon in the upper reaches in nearly 150 years,” said Mike Wilkerson, an Ohio Division of Wildlife fish management supervisor. “When you go back and look at the records different dams were up at different periods of times since about mid-1800s.”

Wilkerson said he’d surmise the fish, which was about four feet in length, was searching out possible spawning habitat.

“That’s really good news,” he said. “I haven’t heard of any being caught in the Sandusky Bay or the river in my 22-year career. You hear about them in the lake, usually one every year. But not in the Sandusky.”

Wilkerson said there’s no downside to having lake sturgeon once again roaming the river bottoms of Lake Erie tributaries.

“It’s a great indication the river’s coming back to where it should be habitat-wise,” he said. “They should be able to make it all the way to Tiffin.”

4 Comments

-

My grandfather caught some sturgeon in Lake Erie and Niagara River during the fifties, and it was always ‘big news’. We have to get them back!

-

My grandfather was born in Cleveland in 1896. He told stories of sitting in ice shanties and spearing sturgeon when they came up to eat a perch tied to a string. He said they would have four guys holding the line to drag the sturgeon back up on the ice. I hope my children can fish with me and see one of these beautiful prehistoric fish. Thanks to the ODNR for helping make this a possibility.

-

What effect, if any, will the yearly walleye run in Maumee River have on these spawning Sturgeon?

-

Only six inch sturgeon? That’s a terrible idea. They should at least be 12” long if you’re going to release them. At that point you’re just feeding the bass and giant catfish that are going to eat them. Yes they have scutes to protect them but that doesn’t mean a large predatory fish isn’t going to try its luck munching on something it hasn’t seen before and kill it in the process before spitting it out.

There’s a fish farm near my house that makes that same mistake but with amur. They only sell 8” amur maximum. Any time someone stocks a pond with them they get all confused when they disappear not realizing that the bass are just eating them all.