Creating clean, safe drinking water used to be a lot easier.

At least according to those tasked with turning Lake Erie water into municipal tap water.

The increasing severity of harmful algal blooms on the lake over the last decade means water plant operators must work extra hard to complete their missions.

In August 2014, Toledo’s water plant shut down for three days due to high levels of toxins in the water. The culprit was a massive bloom, which was producing toxins that made tap water – even after processing at the city’s water plant – unusable for drinking, bathing, cooking and even brushing teeth.

The algae issue has been worked from dozens of angles, including agriculture, urban sewer and stormwater systems, residential gardens and lawn care, wetlands and habitat restoration. Countless studies have been done on the algae itself and its toxin production.

But at the end of the day, the last line of defense against harmful algal blooms, when it comes to safe drinking water, is the operators of municipal water plants. Those operators are responsible for producing potable water for about 11 million people who rely on the lake.

“We first started testing for algae back in 2010,” said Ron Wetzel, superintendent of the Ottawa County Regional Water Treatment Plant. “We started testing when the Ohio EPA told us to and they actually came here to help us sample.”

He explained that microcystin, one of the toxins which algal blooms can sometimes produce, wasn’t the concern it is now.

“It’s ramped up from when they first started talking about the microcystis and now we’re actually testing year-round,” Wetzel said. “Even through the winter months.”

Multi-step process begins out in the open lake

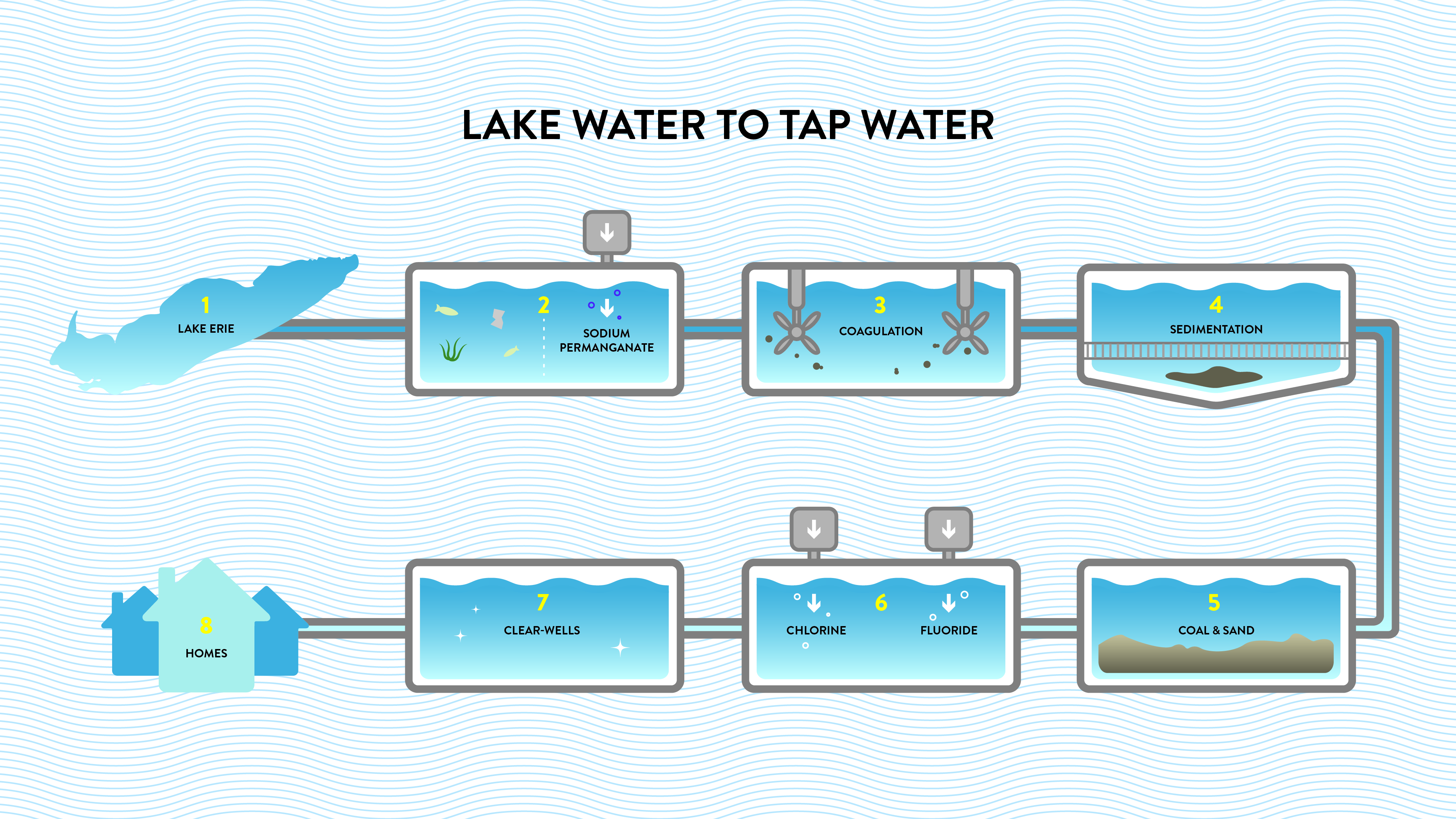

Lake water is sucked into the system through a 30-inch concrete intake pipe located about 1,800 feet offshore in 8 to 10 feet of water. The pipe’s opening is protected by a structure made with large wooden timbers, which are in turn protected by an arrangement of limestone boulders. The intake is inspected annually by camera and cleaned by scuba divers, if needed. Zebra mussels are especially troublesome, operators say.

The next step involves adding a dark purple manganese compound to the raw water after it’s strained for mud, fish, mussels and other debris. The compound, an oxidizer, is so volatile that a worker wiping up a tiny spill saw his rag burst into flame once. This happens at a pump station located in a small block building on the Portage River. Addition of sodium permanganate destroys organic compounds in the raw water, preparing it for further treatment. After that the water is pumped, at a rate of up to 9-million gallons per day, to the water plant a little more than a mile away.

When the water arrives at the plant it’s subjected to coagulation. Carbon powder, aluminum chlorohydrate and polymers are added in a rapid mix that lasts just a few seconds. The compounds stirring together cause the tiniest particles in water to bind together. Microscopic particles that could take years or decades to sink to the bottom of a pool of still water suddenly stick together to other such particles in ever-larger clumps. These masses quickly grow large enough and heavy enough to sink to the bottom of the tanks.

In the sedimentation process, water is pumped into filtration tanks where the coagulated particles are filtered out of the water and sent to retention ponds on the property where the sludge settles. While it never completely dries, it turns into a thick, gray-black muck which is scooped out by crane and trucked to various sites where it is utilized as fertilizer, soil conditioner and in other approved projects every two years.

Massive filters at the Ottawa County Regional Water Treatment Plant in Port Clinton is being backflushed to clear away trapped sediments and contaminants. Photo by James Proffitt

The water that hasn’t been filtered out then flows through anthracite and several types of sand in tanks with a depth of 24 feet.

“When it comes out of there, it’s crystal clear,” Wetzel said.

After the water is made super clear and super clean, it’s injected with fluoride to help prevent cavities. The final step before being pumped into storage tanks and out to homes and business, is chlorination. Addition of chlorine products ensures the cleanest, safest water to the public.

Once the water is “done,” it is stored in two 750,000-gallon tanks called clear-wells and awaits shipment to the more than 8,500 water connections the county serves directly, plus another 9,500 connections in the Port Clinton and Oak Harbor areas.

“Every day we pull about 170 samples out of our water,” Wetzel said. “At all different stages.”

Some are required by the OEPA, but the rest, he said, are simply their own sampling for quality control purposes.

Satellites (and submarines) track algal blooms

While plenty of people on the ground work to create clean water, others are working far above and a little below to help do the same thing.

“We develop satellite algorithms to look at the color of the water and we have a certain algorithm that picks up cyanobacteria,” explained Shelly Tomlinson, oceanographer at NOAA’s National Center for Coastal Ocean Science. The algorithm is used to determine where the bloom is. The information is then combined with data from another research lab specializing in weather. NOAA sends out HAB Bulletins with its forecasts every three days.

Tomlinson and her associates collect data from two different satellites, one American and one European, and in-water measurements are always made to verify the satellite and computer model projections.

“Our plant operators keep a constant watch on NOAA data,” said Gino Monaco, administrator of Ottawa County Sanitary Engineering Department. “They constantly adjust chemical levels and aeration and other factors for whatever water quality issues there are that week. Could be increased carbon, increased chlorine.”

Tomlinson said she knows that plant operators rely on her work and the work of many others, when it comes to managing a threatened resource like water.

“Our forecast is especially important because the satellite imagery only sees what’s happening on the surface of the water,” she said. “In our bulletin there will language in there that addresses wind, which involves mixing. Because that might actually be worse for plant operators since most of their intakes are below the surface.”

NOAA’s Greg Doucette studies stressors and impacts on environments, and Lake Erie is one of his specialties.

“What’s going on under the water is what our primary focus is,” Doucette said, “and, very specifically, targeting toxicity measurements.” Satellite images or pigment concentration doesn’t necessarily say much about the toxicity level of the bloom. A large bloom doesn’t mean high toxins.

Sensors Doucette and other scientists are working with are being deployed to sample Western Basin waters – especially near water intakes.

This underwater autonomous vehicle was recently launched in the Western Basin to help survey the current algae bloom and to assist water treatment plant operators, Photo by NOAA

A stationary unit manipulated remotely, he explained, can measure toxins near the surface or lower in the water column, especially useful when winds cause surface algae to mix into the water beneath the surface.

An autonomous underwater vehicle was recently deployed to survey the lake’s waters and perform lab operations. The AUV takes samples and processes and analyzes information about toxins, sending info directly to scientists in real time.

“Right now there are two AUVs in Lake Erie,” Doucette said. “Understanding intensity and distribution of the blooms under the surface is important.”

He described the first AUV prototype as a sentinel, in that it maps the density of algae in the current bloom. Then, Doucette said, the second AUV heads for hotspots to retrieve data which scientists can use to help understand and combat the blooms.

“It can actually stop and take a sample and basically do a full toxin analysis, surface and transmit the data to us and then we can talk to it while it’s on the surface and then go back under,” he said. “The two vehicles are doing sort of a coordinated mission out there.”

Ottawa County has back-up raw water source

Many water plants rely on just a single source of raw water, but Ottawa County is fortunate to have two intakes: the one in Lake Erie and a second intake a short distance away in the Portage River. The river intake can be utilized in case there’s ever an issue with the main source. Like harmful algal blooms.

Ottawa County’s water treatment plant features a small lab where water samples are tested, Photo by James Proffitt

Originally, the second intake was installed nearly a decade ago to offset the possibility of frazil ice interrupting the county’s water flow. Frazil ice is formed when below-the-surface water is super-cooled by rapid heat loss on the waters’ surface. In Ottawa County, the installation of an intake from a second raw water source has worked out well.

“We’ve had some situations where, based on NOAA satellite imagery, the lake was looking pretty bad,” Monaco said. “So we started drawing a certain percentage of the water from the river intake, instead of 100 percent from the lake. There are a lot of things they throw at us. But we can always make it work.”

While Monaco said having an alternate water source is definitely a serious cushion against pollution by harmful algal blooms and lake pollution in general, knowing what’s going on in the lake and what’s likely to happen next is the best insurance policy.

All-for-one, one-for-all: water systems often connected

While making water potable and combating harmful algal blooms can become complicated and can shut down a water plant, there’s sometimes an escape hatch.

Like being connected to another water system.

Henry Biggert oversees the Carroll Township water plant, in a rural area a few miles west of Port Clinton. His plant also draws water from the lake. And like Toledo in 2014, Carroll Township in 2013 suffered the wrath of harmful algal blooms. The Carroll Township plant was offline about four days.

“Knowing what we know today that same scenario would never happen again,” said Biggert. “We had actually sampled on a Tuesday and didn’t necessarily believe the numbers and so we resampled on a Wednesday. When that sample came back positive for microcystins we made the call to issue a do not use advisory, which came in probably about 6 p.m. on that Thursday.”

Biggert kept his system offline, opting to open up a pre-existing connection with Ottawa County’s water line. During those days, the county simply ramped up water production and fed Carroll Township’s residents.

“Once our system was completely flushed of our contaminated water, we went back online,” Biggert said.

According to Biggert, the data and information currently provided by scientists fills in a gap in both awareness and knowledge that was present five or six years ago.

“We’ve really learned a lot since then,” he said. “We’ve all learned a lot more about what it is and also how to treat water when it’s present. What happened here in 2013 and in Toledo in 2014 isn’t likely to ever happen again. There’s too much information and everyone is so much more aware now than they used to be. We know what’s coming and we can prepare for it.”

Featured Image: Algae-laden water currently being drawn from Lake Erie in Port Clinton, Ohio. Photo by James Proffitt

3 Comments

-

Amazing, with all the algal problems we have, nobody seems to mind that EPA never implemented the CWA, by ignoring urine in sewage, an oxygen robber and fertilizer for algae. Not because, as EPA now claims, Congress intended , but because of a faulty applied test to establish sewage treatment standards.

By using the 5-day test reading of the BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) test, instead of its full 30-day reading, EPA not only ignored all the nitrogenous pollution in sewage, but only requires 50% sewage treatment. A far cry of the CWA’s goal to eliminate all water pollution (100% treatment) by 1985.

The incorrect use of the BOD test is causing many other mostly engineering problems, like we still do not know how sewage is treated, possibility exist tgat multi-million sewage treatment plants are designed to treat the wrong waste, just to name a few. History and description of the BOD test: Wp.me/p5COh2-25

Unfortunatky, for some reason, nobody seems to care. Meanwhile blaming farmers, while the fertilizer they use to grow the food we eat, ends up in our open waters. The pot is calling the kettle black! -

I THINK YOU MEAN THEY ADD POTASSIUM PERMANGANATE NOT SODIUM

-

we are looking technology to treat lake. Location in sate of Pahang, Malaysia