July 30, 2019: This story was updated to add comment from Aquila Resources and a response to that from the Menominee Tribe.

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula has long been the grounds for many battles between mining interests and residents, including several Native American nations.

One of the current ongoing conflicts is between the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin and Canadian mining firm Aquila Resources whose slated project threatens their ancestral lands.

Menominee oral traditions and beliefs hold that their people first came to be when a Great Light-colored Bear emerged from the underground at the point where the Village River (Menominee River) meets the Bay In Spite of Itself (Green Bay). The Bear traveled upstream for many days, speaking all the while with the Grandfather, the creator of the Earth, Sun and stars. Upon seeing that the Bear retained his animal form, Grandfather allowed him to transform into a man. Thus the first Menominee man was born.

Ceded to the United States through seven treaties signed between 1821 and 1848, this territory along the Menominee River is the sacred, ancestral home of the Menominee Nation. It is also now the proposed site for an open-pit gold and zinc sulfide mine referred to as the Back Forty Mine.

“In contrast to other industries, we cannot choose where to operate,” Chantae Lessard, director of social performance and engagement for Aquila Resources, said in an email.

“Mining can only take place in areas where minerals are present in economically viable deposits. Today, we have the technology and experience necessary to ensure that mining is safe and protective of the environment. We can have both a strong economy and a clean environment.”

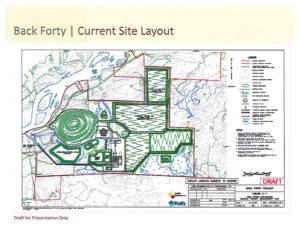

A Toronto-based development-stage company, Aquila Resources has been pursuing the necessary permits from Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE, formerly Department of Environmental Quality) to begin construction of mine facilities, including a waste management building slated to be constructed only 150 feet away from the Menominee River.

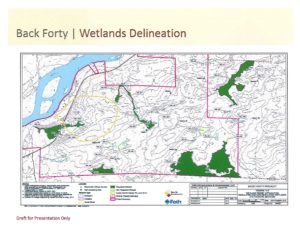

The Department of Environmental Quality granted a wetlands permit on June 4, 2018, the fourth of five permits Aquila needed after receiving ones for air quality, wastewater management and mine construction.

The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin filed a lawsuit against Aquila Resources in November 2018, arguing that the state of Michigan did not have the initial authority to grant the company the wetlands permit. Under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, states can assume administrative responsibilities normally utilized by the EPA for waters within their borders. Only Michigan and New Jersey have taken on these responsibilities.

Menominee Tribe Chairman Douglas Cox explained that their lawsuit asserts the Menominee River is a commercial interstate waterway, which under Section 10 of the Clean Water Act would automatically delegate authority to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, not Michigan.

The case was dismissed on December 19, 2018, and is now being appealed by the Menominee Tribe in the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

Opposition to the mine, however, goes much further back than this lawsuit from the Menominee Tribe.

Al Gedicks, a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Lacrosse, is a vocal critic of the proposed mine. He has written op-eds on the perceived risks of Aquila’s planned mining and waste management facilities, and is executive secretary of the Wisconsin Resources Protection Council, an activist group formed in 1982 to raise awareness of the potentially negative effects of metallic sulfide mining.

“This project is located on the land of a sovereign nation, the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, whose historical village is located on the mine site. Their resources, cultural resources…there are ancient village sites, burial mounds, their raised garden beds which are an archaeological wonder, recognized by archaeologists, have been ignored by the state of Michigan,” Gedicks said.

“When the United States government hands over that federal authority, they’re really handing over the government’s trust responsibility to tribes,” Cox said, citing the 1836 Treaty of the Cedars signed between the United States government and the Menominee Nation.

While the treaty signed over Menominee land to the federal government, there was a tacit understanding that the United States had a “duty of protection” to the tribes and their cultural and natural resources, he said.

“Therein lies the problem” Cox said. ”The state took on the program without acknowledging they were taking on that federal trust piece.”

Cox also noted that when Aquila Resources was first prospecting the land, no formal government-to-government consultation was established between the Menominee Tribe and Michigan. It was only via Native American communities in the Upper Peninsula that the Menominee Tribe was made aware of the ongoing talks between Aquila and state authorities.

In 2015, Aquila Resources approached the Menominee Tribe to explain what its plans were for the Back Forty Mine, assuring that it would do due diligence to protect Menominee cultural sites.

“A general promise is what they stated to me and the tribe,” Cox said. “It was nothing binding because I think they knew they were going through the whole permitting process. None of them had even been issued at that point.”

“We wanted our own archaeological resources involved in the survey, which they never did,” he added. “We wanted on-site monitors when construction began, which they wouldn’t do.”

Lessard restated that “the Back Forty Mine will not disturb any identified cultural resources,” drawing attention to a provision within their mining permit requiring an “Unanticipated Discovery Plan in the event of finding a cultural resource during operation.”

“This has been about a 16-year battle, it’s been around for quite a while,” said Guy Reiter, executive director of Menikanaehkem, a grassroots community organization based on the Menominee reservation in Keshena, Wisconsin. The group has been one of the spearheads of the “No Back Forty” movement as protectors of the Menominee River, with Reiter having been involved for the past 9 years.

“Sulfide mining is the dirtiest mining,” he said. “The thing with this particular ore body is it’s locked in sulfide rock, so as soon as it’s exposed to water and air it creates sulphuric acid. There’s no other way around it: chemistry is chemistry.”

In the meantime, Aquila continues to pursue the permits it needs to establish its mining operation. Of the five permits Aquila has been granted or submitted applications for, only two have been finalized, those being for air quality and wastewater management. The wetlands and mine construction are still working their way through the contested case hearings.

Reiter, representing Menikanaehkem, spoke at a public hearing on June 25 in Stephenson, Michigan, on the Back Forty’s dam safety permit, which included public comment on the proposed tailings dam.

EGLE is still receiving public comment on the dam safety permit until July 23. Comments can be sent via e-mail or phone call to the contacts listed here.

Featured Image: Aerial view of Menominee River near mine site, Photo by Kiliii Yuyan via Ian Wendrow