Mining helped to build the economy of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, but it also has courted controversy for its environmental and cultural impact.

Canadian company Aquila Resources’ Back Forty Mine has resurfaced long-standing disputes on how to reconcile the immediate economic needs of a community with the potential, long-term impacts mines and their waste leave on the land.

A significant point of concern among some residents and the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin is how Aquila plans to handle the inevitable waste material that will be produced during the mine’s operation.

Separating zinc and gold deposits from sulfide rock requires complex chemical interactions that ultimately end up as tailings: a combination of waste rock, water and toxic chemicals such as cyanide and arsenic.

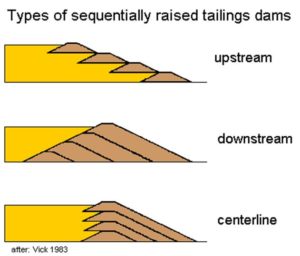

Aquila Resources’ permit application suggests the construction of what is known as an upstream tailings dam to hold the tailings. Upstream dams are used in other sulfide mines, but there are allegedly safer methods of tailings dam construction while upstream tailings dams have sometimes resulted in catastrophic failure.

In Brazil, an upstream tailings dam at an iron mine near Brumadinho burst in January, 2019, spewing forth toxic waste that killed at least 237 people. The mine was not one of Aquila Resources’ dams. But critics of Back Forty worry that despite guarantees from Aquila, the risks of such a disaster outweigh any benefit the mine could bring.

The Center for Science in Public Participation, a nonprofit corporation set up to provide technical assistance and policy recommendations on mining and its effect on the environment, published its own report on Aquila’s mine permit application.

“You don’t want any water getting into the dam, because it exponentially increases the chance it could fail, but it’s impossible to prevent water seepage entirely,” said Dr. David Chambers, a California geophysicist and president of the Center.

Diagrams of different tailings dam construction methods, the yellow signifies where the waste rock/tailings would set against the structure. Image from ‘Planning, Design, and Analysis of Tailings Dams’ Image by Steven Vick via Ian Wendrow

“The primary reason to use upstream-type construction is to save money. Any time tailings are used for structural support, the risk of failure is increased over that of mechanically engineered materials,” he added, quoting the report he co-authored with Kendra Zamzow.

Both authors note that the purported dangers of using an upstream dam is elevated due to an under-estimated seismic analysis used by Aquila Resources in their Mining Permit Amendment Application.

“Typically, projects like these should use a 1 in 10,000 year seismic event analysis… Aquila’s proposal only used a 1 in 2,500 year model,” Chambers said.

With long-lasting structures like dams, the proposed design’s ability to withstand significant seismic events is analysed, a “what if” model used to ensure the construction is resilient over the long term. Though the operational life of the mine is estimated by Aquila to be around seven years, the upstream dam housing the tailings waste will effectively stand in perpetuity after it is sealed following the conclusion of mining operations.

Chambers and Zamzow argue that a dam built for a project as large as the Back Forty should be designed to withstand the probability of damaging earthquakes occurring over a period of 10,000 years, as opposed to just 2,500.

However, not everyone shares the Center’s skepticism of upstream dams.

“I wouldn’t agree that the upstream approach for the construction of a tailings basin is inherently unsafe.There are several examples throughout the world and even in the state of Michigan,” said Luke Trumble, a dam safety engineer for EGLE’s Water Resources Division.

Worldwide, there are about 3,500 tailings dams in use, half of which use the upstream construction method, according to a report published by AGRA Earth and Environmental Limited engineering firm (now AMEC).

Others offer an even more charitable view of the Back Forty’s potential.

“The mine’s become a high priority for me, I believe it should be a high priority for the district,” said Republican Sen. Ed McBroom, representing Michigan’s 38th district comprising the western half of the Upper Peninsula including Menominee County, where Aquila Resources intends to build its mine.

“We’ve seen the Eagle Mine project go on up in Marquette and the tremendous boon that’s been to the economy as well as the excellent job they’ve had with protecting the environment. That’s why I’m very excited to see this project here in this area.”

A dam safety application submitted by Aquila Resources at the beginning of this year is currently under review, concerning the tailings dam and contact water basin facilities. The design proposals are being reviewed under Part 315, or the Dam Safety Statute, of the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act.

“Just because it’s utilizing the upstream method wouldn’t necessarily disqualify it from getting a permit,” Trumble said.

“We would look at the design, ensure that it meets appropriate factors of safety, that any of those conditions that were present in those dams that did fail have been accounted for in the design, and if it can be demonstrated that it is a safe design and can perform safely, then we could potentially issue a permit for that construction method.”

Water Resource Division’s Finding of Fact report, showing 900 acres of state land east of proposed project site with lower concentration of wetlands area and further distance from Menominee River itself

Another sticking point for activists is the way the wetlands permit was granted. EGLE’s Water Resources Division is charged with ensuring Aquila’s application abides by environmental health and safety regulations under Michigan’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act 451.

The division found that the proposed Back Forty project “does not demonstrate that an unacceptable disruption to the aquatic resources of the State will not occur,” according to its Finding of Fact report. In other words, the permit did not adequately prove the surrounding environment would not be harmed by mining operations.

The Finding of Fact report was published on April 30, 2018. Yet just five weeks later, EGLE’s former director issued the wetlands permit to Aquila Resources after an Environmental Protection Agency review.

The brief period between the Water Resources Division’s report and the permit’s initial approval raised eyebrows, considering the report stated that Aquila’s application used an incomplete groundwater model and failed “to determine that offsite alternatives are not feasible and prudent.”

These issues and others are currently being deliberated in administrative contested case hearings between Aquila Resources and EGLE, the latter represented by attorneys from the Attorney General’s Environment, Natural Resources and Agriculture Division, according to communications director Kelly Rossman-McKinney.

“AG Nessel and her team will continue to monitor the situation and evaluate whether she needs to take any additional action,” Rossman-McKinney said in an email.

Of the five permits Aquila has been granted, only two have been finalized, those being for air quality and wastewater management. The wetlands and mine construction permits are still working their way through the contested case hearings while the mine dam safety permit is still receiving public comment until July 23.

Comments can be sent via email or phone call to the contacts listed here.

“EGLE remains committed to protecting public health and the environment and will give this project full regulatory scrutiny as required by statute,” said Scott Dean, strategic communications director for EGLE in an email.

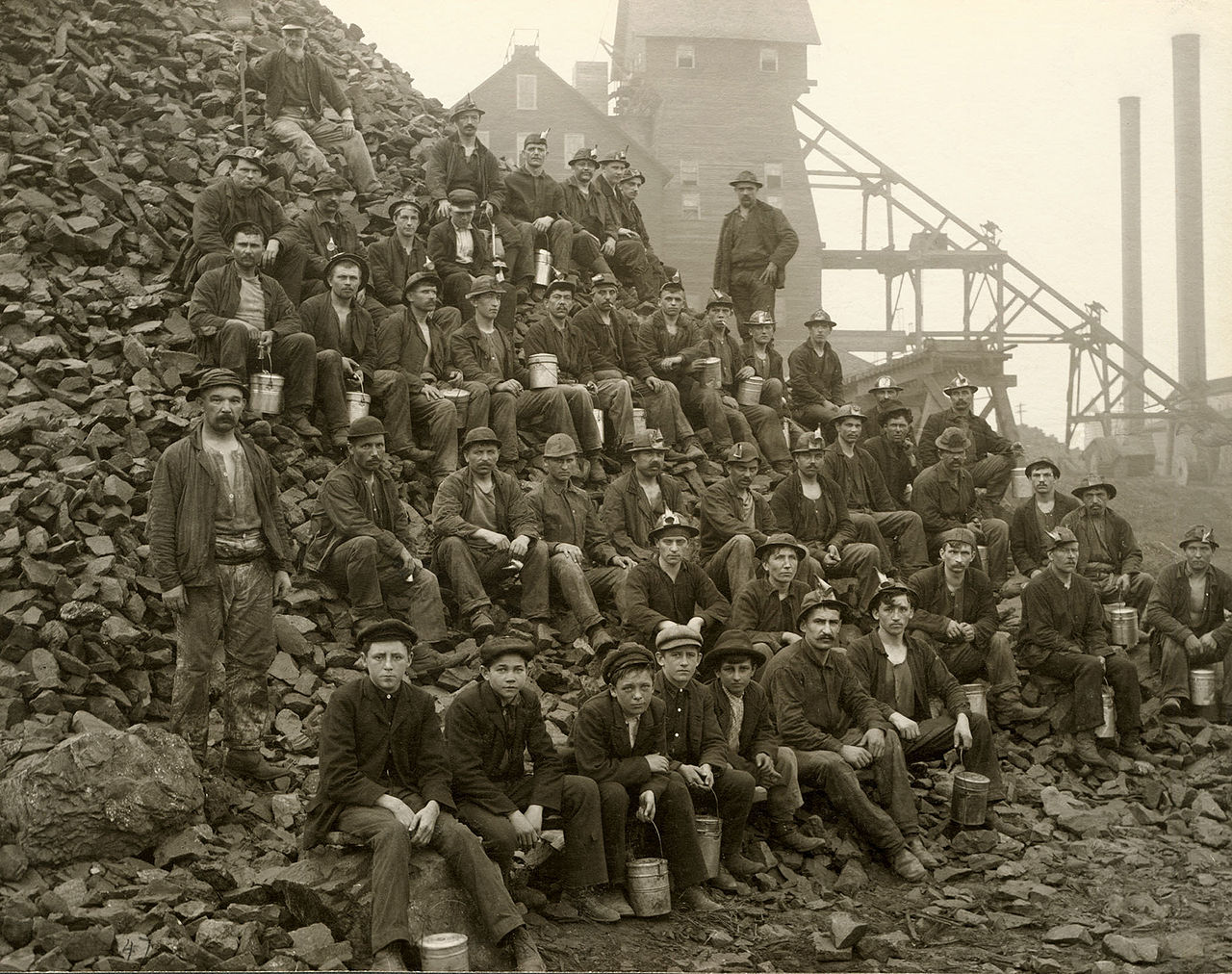

Featured Image: Miners pose with lunch pails in hand on a pile of “poor rock” (waste rock) outside of the Tamarack mineshaft, Photo by Keweenaw National Historical Park Archives, Jack Foster Collection via wikimedia.org (Public Domain)