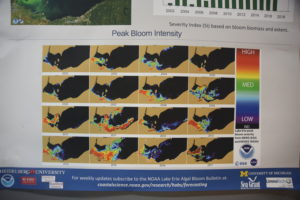

The early season projections for Lake Erie’s harmful algal blooms this year started at “greater than five” on a scale of 10 on the severity index and have since been raised to “greater than seven” in subsequent projections.

The forecasts, issued by the National Center for Water Quality Research (NCWQR) at Heidelberg University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) offer insight into the likely severity of the blooms to assist operators of drinking water plants, recreational users of the lake and tourism officials, among others. The forecast scale refers to the projected size of the bloom. Until the bloom actually occurs, its toxicity level is unknown.

The 2019 forecast offered by NOAA stands at 7.5 – worse than last year but not as bad as the 2011 and 2015 blooms, which were 10 and 10.5 respectively.

The final forecast was issued on July 11, after precipitation events that directly contribute to algal blooms concluded.

At this point, not much can affect the size of the blooms

“From what we’ve found in the past, it takes about a month for rainwater to turn over,” said Rick Stumpf, oceanographer with NOAA. “So pretty much once we’re into July, once you get past that, there’s really not an indication that it can increase the bloom.”

Harmful algal blooms are fed in part by the nitrogen and phosphorous found in agricultural fertilizer and animal manure, originating on lands within the Maumee River watershed which spans three states. Heavy spring rains can exponentially increase the amount of fertilizer running off fields and correlates directly to the algal blooms that appear later in the season.

While rain was down .33 inches in January, according to averages, it was up through late June a total of more than six inches.

“The way it started for June, we’re leaning toward being overly wet,” Tom King, meteorologist with the National Weather Service Cleveland, said. “It’s likely to be more than normal for the month.”

One thing that could still affect the size of the blooms is the temperature of Lake Erie, according to Stumpf.

“If it’s too cold they won’t form,” he said. “The water needs to get warmer before they can really get started, which is a good thing for an event like this. Cooler temperatures may give it enough time for the nutrients to get used up by other things in the water before the cyanobacteria can use them.”

Heavy rains bad for farmers but good for Lake Erie

According to Laura Johnson, director of the National Center for Water Quality Research at Heidelberg University, what Ohio farmers consider too much rain may actually be a good thing—at least for Lake Erie.

“We don’t have as much (nutrients going into the lake) as we would have expected based on how much water volume is coming out of the Maumee River,” she said.

An especially rainy autumn, combined with a similar spring, has kept many farmers out of their fields and pushed back spring fertilizer applications, Johnson said.

“If you talk to anyone in the farming community right now, you’ll know they’re having some challenges out there this year,” she said. “It’s been pretty wet, all the way back to last fall. Very few farmers applied any phosphorous fertilizer last fall.”

“What it suggests is that it’s not as bad as it could have been,” she added. “It looks like there are some early indications that the things that are negatively impacting farmers now may have a positive impact on the lake.”

Laura Johnson, Director of the National Center for Water Quality Research at Heidelberg University, Photo by James Proffitt

The monitoring of water entering Lake Erie is a well-established project.

“Our longest-term monitoring stations are on the Maumee and Sandusky rivers, where we started sampling in 1974,” she said. “We collect samples three times a day using an automated sampler and collect these year round.”

The samples are retrieved weekly and analyzed for concentrations of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous. In total, Johnson said, her program collects samples from about 25 stations in Ohio, with a handful in Michigan.

The record-high water levels in Lake Erie are helping mitigate the forecast algal bloom as well, according to Stumpf.

“There’s about 10 percent more water in the Western Basin right now,” he said. “There’s a lot of low-nutrient water flowing through from Lake Huron, from the Detroit River. We’re not as bad as we could have been because of the amount of water entering the lake.”

But even if this year’s bloom does reach 7.5, or even greater, that doesn’t mean the lake cannot be enjoyed, Stumpf said.

“It’s not everywhere on the lake,” he said. “The blooms move with the wind and the weather. I can’t tell you where it will end up. But calm water and hot weather made the 2017 bloom especially bad.”

Algal bloom forecast is closely watched

The algal bloom predictions are important to different folks for different reasons. When it comes to tourism, Larry Fletcher, president of Lake Erie Shores and Islands, a regional tourism office, wants a low algal bloom forecast so the maximum number of visitors can enjoy the region’s many offerings.

When asked if a forecast of a big bloom means people shouldn’t come to the lake, he was quick to answer.

“Absolutely not, it doesn’t mean that at all. Every year, no matter what the size of algal blooms are, it’s a dynamic situation because a bloom might be present in one small portion of the lake and not another,” Fletcher said. “It really has to do with where a person’s going and what contact they’ll have with the water.”

He added that despite health bulletins warning about possible toxins that may be produced by algal blooms, he hasn’t seen any issues.

“I haven’t personally seen anyone get sick,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean people still shouldn’t exercise caution when certain conditions exist.”

Anyone interested can track the latest HABs in real-time with NOAA’s experimental satellite tracking website.

Few reported cases of health issues, but caution still advised

While the algal blooms are unsightly, it’s the microscopic plants’ ability to produce neurotoxins that is most worrisome.

Under certain circumstances, toxic algae can produce cyanobacteria toxins which include neurotoxins (which affect the nervous system) and hepatoxins (which affect the liver). In 2014, it was the presence of toxins in Lake Erie’s Western Basin which shut down the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant in Toledo for several days. A year earlier, the Carroll Township water plant east of Toledo shut down briefly due to the presence of toxic microcystins.

Barbara Saltzman, assistant professor at University of Toledo’s School of Population Health said the first year of a two-year study on harmful algal blooms and human health has yielded positive results with no definitive illnesses that could be attributed to algal toxins.

“Last year we mailed postcards to randomly selected voters, anglers and shoreline residents,” she said. “We basically wanted to see if people were reporting any health problems that could be attributed to HABs. Last year was a really light season for HABs and so we didn’t really see a lot going on.”

Saltzman said only a handful of people who responded online to the short survey reported symptoms.

“But those could have been due to anything,” she said. “One or two people with gastrointestinal symptoms, a rash, but really almost nothing was reported. And that’s great. But I still recommend following all health advisories because they are based on science.”

The Ohio Environmental Protection agency provides health advisories regarding harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie, which includes keeping dogs from swimming in and drinking lake water when blooms are present. Saltzman said this year’s survey will also include questions pertaining to pets.